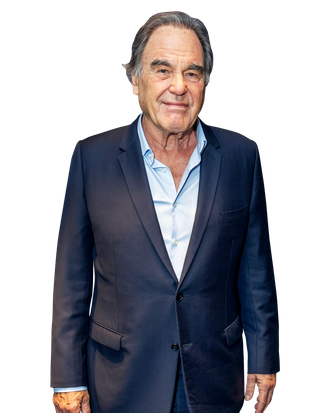

Last week, Oliver Stone welcomed guests to the Navy Memorial Theater on Pennsylvania Avenue for a screening of his latest documentary, Nuclear Now, which is playing in NY and LA and hits VOD on June 6. With Joshua Goldstein, a professor at American University and the author of A Bright Future, the filmÔÇÖs foundational text, Stone makes an environmentalistÔÇÖs case for nuclear energy with aesthetic and narrative nods to An Inconvenient Truth. It is a surprisingly wonky affair, with more in common with a Vox explainer than with Nixon or W. But perhaps thatÔÇÖs because StoneÔÇÖs feelings about this issue are so uncomplicated. It is his belief that a great fraud was committed ÔÇö with the help of Big Oil ÔÇö to shut down the construction of nuclear facilities, a scandal that robbed the world of the beautifully efficient future we were promised in the 1960s. After the screening, Stone elaborated on the project and shared his pessimistic outlook on the movie business.

How did you decide to approach this as a documentary versus a feature?

ItÔÇÖs a complicated one. The book inspired me. It was reviewed in the Times by Richard Rhodes, and it was in the middle of all of this confusion. Confusion motivates. If you donÔÇÖt understand the world around you, you can feel ignorant and lost. The whole search for meaning, search for truth, is crucial. To me, energy is the most important subject because energy makes the world go. So what is it? And how does it work? People can be very confusing when they talk about forms of energy. Wind, sun, hydropower, geothermal ÔÇö all of them are good. Oil? No. Coal? No. Nuclear, certainly, was at the back of everyoneÔÇÖs mind, but we forgot about it. If you look at my films, there are a lot of times where I dig into something and I find thereÔÇÖs a lie. To me, there was a lie about the presidency.

Which one?

Kennedy. And there was a lie about Vietnam, there was a lie about Wall Street, there are lies about football. My movies explore that. So there was a motivation there. But that wasnÔÇÖt the original motive. I didnÔÇÖt realize there had been a nuclear fraud in the 1970s with this movement to stop it. That was not the issue. It was about, How does it work? The book was very clear. It is heartbreaking, when you really get into it, and you think about, Wow, we were going on our way. By now, weÔÇÖd have a thousand nuclear reactors. There would have been a few accidents. ThatÔÇÖs the price you pay to develop an industry. Every industry has setbacks. The chemical industry ÔÇö constantly. You saw the train wreck in Ohio. ItÔÇÖs tough. ThatÔÇÖs the nature of it. But we became averse to any kind of accident. We have to take risks to get anywhere ÔÇö the world was built on risk. That really bothers me.

I was thinking about Kubrick and Dr. Strangelove. As a filmmaker, why take the documentary approach? Why not process this in a narrative?

I tried, I tried, I tried. I asked Josh [Goldstein] to write me a nuclear fiction story. A thriller. And he tried, he really did. But it was a ridiculous movie. It was just another film that would have come and gone.

You thought his script was ridiculous?

I donÔÇÖt know if he got to the script stage. It was more like a treatment. HeÔÇÖd never written anything like that. But I couldnÔÇÖt save it. Normally I come in and work on a script, but I couldnÔÇÖt save this thing. It was silly. I mean, a ÔÇ£female scientist tries to save the worldÔÇØ kind of story isnÔÇÖt going to work. This is bigger than that. ThereÔÇÖs no way to deal with this that way.

No way?

Eh, I donÔÇÖt want to. Maybe someone could take this and be inspired by it. But not me. If you come up with an idea, send it to me.

DidnÔÇÖt you rewrite Natural Born Killers?

This is tough stuff to dramatize. There are complications. You make a feature, itÔÇÖs going to cost ten times as much and youÔÇÖre going to have actor issues.

Actor issues?

Well, money! The system is now built around ten or 20 stars, and you have to pay a fortune for them, which is silly. It shouldnÔÇÖt work that way. In the old days it never did, and they made a great business that way. You have to make movies with stories. Stories come first. But now the actors come first.

And you donÔÇÖt see a way around that as a filmmaker?

No, I donÔÇÖt see a way around that.

YouÔÇÖre an Oscar-winning director. I assume you have tremendous power.┬á

I certainly have been at the top of the profession, and IÔÇÖve seen it at its best and at its worst. There have been changes since the ÔÇÖ90s ÔÇö now, itÔÇÖs more difficult. The advertising and the marketing keep going up and up and up. ItÔÇÖs a deal. You have to figure out, How do I sell this before I even make it? which is ridiculous. Before, you made the movie first, then you worried about how to sell it.

How did you fund this movie?

All private. Fernando, some of his friends. ItÔÇÖs not big money anyway.

WhatÔÇÖs the budget like?

About two and a half million.

How long did it take?

About two and a half years.

What are you anticipating in terms of the reaction?

IÔÇÖm not expecting anything. YouÔÇÖre in Washington; you understand the crosscurrents. How does anybody get attention on anything? ItÔÇÖs ridiculous. The world is so fast moving. WeÔÇÖre a tiny little blip. But I think itÔÇÖs one of the most important things if not the most important thing. We should get past politics, get past ideologies, bring together countries, and we can solve it.

You seem to be implying that narrative pursuits are silly compared to this.

At this point, IÔÇÖve made 20 feature films, ten documentaries. ThereÔÇÖs no one movie that has an idea and can really be that original right now. WeÔÇÖve done so many good movies. Look at the history of movies; we havenÔÇÖt even seen half or a third of whatÔÇÖs out there. I watch a lot of old movies, and IÔÇÖm just astounded. Why redo it all? ThereÔÇÖs no reason. Unless you make the bows and you paint it a bit brighter, but itÔÇÖs all that money wasted. If we didnÔÇÖt make more movies right now we could probably live off of what we have. LetÔÇÖs fix the world first.

YouÔÇÖre so optimistic about human innovation.

Yeah, have to be.

But not when it comes to art.

ThatÔÇÖs true. ThatÔÇÖs well said. What was the Best Picture? Everything Everywhere All at Once. Okay, I guess thatÔÇÖs original. ItÔÇÖs original. I havenÔÇÖt seen that idea.

YouÔÇÖre kind of bumming me out.

I donÔÇÖt mean to. But IÔÇÖm not interested in identity politics.

And you think thatÔÇÖs impossible in Hollywood right now, to avoid that?

Diversion ÔÇö what is it, inclusion?

Diversity and inclusion?

I saw Camelot the other day in New York. It was, [disapproving guttural sound]. It was the inclusion version. It was such a great play when I saw it with Richard Burton and Julie Andrews and Robert Goulet. But they changed it. They tampered. They watered it down. So it tastes like gruel.

So when you see that someone like Francis Ford Coppola is still killing himself making Megalopolis, his great opus, what do you make of that?

That is very interesting. I wish him well. He put his own money up, too. Wonderful, I love that. ItÔÇÖs a Moby-Dick story. IÔÇÖm looking forward to it. But itÔÇÖs very hard to make movies.

But you consider it a wasteful effort.

Its a huge effort. Poor Francis. If he doesnt make it, hes gonna  well, he always comes out on top of these things. Hes smart. Very smart.

In a perfect world, what would be the reaction to this documentary?

TheyÔÇÖd start building again! TheyÔÇÖd throw out the NRC, which is a joke. It should be like the FDA, which allows new drugs. IÔÇÖd like to have a little nuclear power plant in my house.

Would you live next to a nuclear reactor?

Of course I would! What are you talking about? ItÔÇÖs the safest thing in the world. IÔÇÖd take refuge there in a war. Where you fear things is where you go.