NetflixÔÇÖs new series Deaf U is a fun, fascinating look at the lives of several students who attend Gallaudet University, a school for the deaf and hard of hearing in Washington, D.C. ItÔÇÖs being marketed as a ÔÇ£docusoap,ÔÇØ and the term is not a bad fit for how the series is both a docu-style deep dive into many cultural nuances of the deaf community, and also a gossipy unscripted teen drama. Some of the students featured on the show, like Tessa Lewis, come from ÔÇ£eliteÔÇØ deaf families, meaning that they were raised by deaf parents and attended deaf schools from early childhood. Others, like Cheyenna Clearbrook and Daequan Taylor, attended mainstream schools and had little experience with deaf-centric education until arriving at Gallaudet.

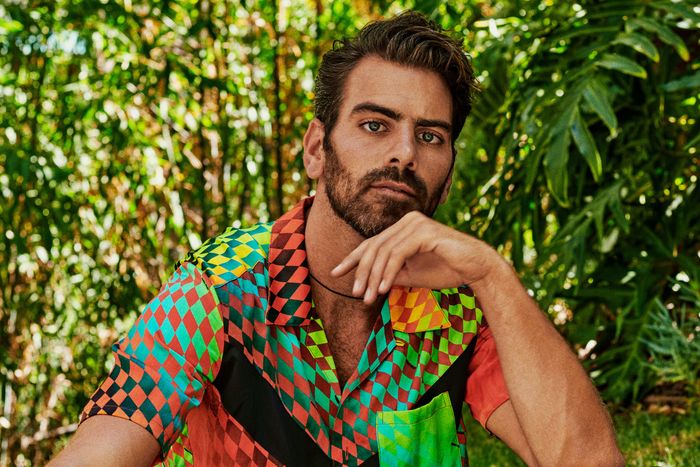

One of Deaf UÔÇÖs executive producers is Nyle DiMarco, who became famous as one of the first deaf contestants to appear on unscripted television. DiMarco had prominent runs on both AmericaÔÇÖs Next Top Model and Dancing With the Stars, and became interested when he learned a production company was considering shooting a series at Gallaudet. Vulture spoke with DiMarco about becoming involved with Deaf U, his hopes and goals for the series, and how to make a show about deaf culture that doesnÔÇÖt become a PSA.

How did you become involved in this series?

Two reasons: One, IÔÇÖm an alum of Gallaudet University. I love it there; itÔÇÖs my home. And second, for my run on AmericaÔÇÖs Next Top Model and Dancing With the Stars. For both of those experiences, I was the only deaf competitor on a reality-TV show. At the time, IÔÇÖd go through interviews and theyÔÇÖd ask me questions specific to my deafness ÔÇö nothing about who I am, what IÔÇÖm like, my favorite foods, nothing. It was this one-dimensional mask that I was forced to wear. So Deaf U became this opportunity to navigate into this world, to really experience this world and how rich it is, how rich deaf studentsÔÇÖ identities are.

Did someone come to you and say they were interested in this project? Were you seeking out producers?

Funny enough, actually, the production company Hotsnakes had shot a sizzle reel, a few scenes with some students at Gallaudet a few years ago. A friend of mine texted me and said, ÔÇ£Hey, it seems like theyÔÇÖre trying to make a reality TV show on campus, but IÔÇÖm not really sure what the story is because there are no deaf people behind the camera. ThereÔÇÖs no one involved in production.ÔÇØ

I said, ÔÇ£All right, let me make a quick phone call.ÔÇØ My team reached out, and their agent told them to reach out to Nyle DiMarco, so it just so happened that we were both looking for each other at the same time. They had already offered me a cast that they were interested in, and when they showed me that cast I said, ÔÇ£You know, some of these students canÔÇÖt sign that well.ÔÇØ They said, ÔÇ£Oh, we didnÔÇÖt know that!ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs a language fluency differential; thereÔÇÖs diversity within that. ThereÔÇÖs so many layers to deaf representation, solely based on language representation.

From there, did you bring other deaf participants onto the production side of the show?

I did bring other deaf people in. Once I got involved, I had a chance to work with their team, and for one deaf person to really authentically view the whole range of deaf experience is really impossible. So it was really key that we brought other deaf talent into the production process.

We also established a contract with Gallaudet University, and part of that was a requirement that we meet a minimum of 30 percent deaf crew working on the show. We exceeded that number, and reached 50 percent, which is unprecedented in the entertainment industry.

Are there any kinds of deaf stories in particular you were hoping to tell with these specific cast members? They have such a range of experience with deafness, with Gallaudet, with each other.

I was most interested in students who had come into Gallaudet without any access to American Sign Language prior. When I was a student at Gallaudet, I met so many other deaf students who arrived with no knowledge of the language, no knowledge of the culture. But they would come in and by four years of being there, they would be furious that theyÔÇÖd never had exposure, and very resentful that they were at a linguistic delay. I found that was an incredibly universal experience in the deaf community; itÔÇÖs quite common.

I definitely had a tough time convincing Daequan to join the cast. At the time when I met with him, he said, ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt think I should be involved because I donÔÇÖt think I represent the deaf community.ÔÇØ The conversation that I had with him was that he actually in fact does represent the majority of the deaf population within the United States.

It was fascinating to me to see Netflix marketing it as a docusoap. Is that something the production was aiming for at the beginning? Did that develop later, as you were editing?

You know, to be honest, I didnÔÇÖt want to make a PSA. I wanted something that would draw hearing people into our world and say, ÔÇ£Oh, deaf people go through the same things as we do.ÔÇØ That was the goal: to see the drama between these students.

Does your past experience being on reality shows give you a different sense of how production works, or change your relationship with the cast members? Do you feel protective of them?

Yeah, my primary goal is that I want to protect the deaf community. Like Tessa, for example. Tessa has so many important things to say, itÔÇÖs just a matter of reframing what those things mean. ItÔÇÖs possible that her intention is really hard for hearing people to take away from her, but I do agree with her in so many ways. Obviously through her experience, I wanted to help her and see if it was possible for her to open up to her intention.

For myself, as someone coming from what would be called ÔÇ£elite,ÔÇØ coming from a deaf family, I want to see Tessa really explain the deep meanings behind the fact that ÔÇ£eliteÔÇØ really means having access to language since birth. Having access to language means having access to education and so many other things. Within the deaf community, those who come from deaf-of-deaf families and go to deaf schools are really the minority, and sign language is on the brink of extinction.

So Tessa is of course very protective of the deaf community, and I wanted to pull more out of that without villainizing her. I do hope that in a season two, the cast will see and other students will see our motivation in supporting the community.

ItÔÇÖs interesting to hear you say that you didnÔÇÖt want to villainize Tessa. It does feel like her words are put up against those of other cast members, and the audience is being asked to see how she views the world versus someone like Daequan, who comes from so much less privilege.┬á

I do think a lot of people looking at Tessa and her experience will see that it is completely different than Daequan. Of course he didnÔÇÖt go to a deaf school, and so coming to Gallaudet, Daequan mightÔÇÖve felt alone. ItÔÇÖs also true for someone like Cheyenna, having to make new friends. ItÔÇÖs already hard enough to join an established group of friends like TessaÔÇÖs, who all grew up together. TheyÔÇÖve known each other from their kindergarten days. That group is most comfortable with one another.

But at the same time there, there is a bit of a survivalist mentality. I moved to three different deaf schools, and it was because my parents were looking for the best education out there; they were looking for the best way for me to thrive. I really believe thatÔÇÖs where TessaÔÇÖs coming from.

What has surprised you most about making the show, and watching how people have responded to it?

The hearing audience reaction to it has been a big surprise. TheyÔÇÖre loving it; itÔÇÖs been incredibly positive. WeÔÇÖve started a deep dive into the community that weÔÇÖve never seen before, and the best part is that for a deaf person like me, weÔÇÖve only scratched the surface.

As far as making the show, my biggest surprise (spoiler alert for the end of the season) is that Alexa went back to Braxton!

I know! I couldnÔÇÖt believe it! Alexa, why did you make that choice?!┬á

Yes! ItÔÇÖs like, What?! I felt the same way, but to each their own.

Can you give me some specific examples of how having such a large deaf crew changes the end result of the show?

We can recognize language fluency between the cast. Hearing people donÔÇÖt realize that until itÔÇÖs made explicit that language fluency is important, and that itÔÇÖs based on systemic oppression. ItÔÇÖs crucial to have deaf people behind the camera to make sure that weÔÇÖre not showing people as one-dimensional.

Another example is Tessa versus Cheyenna. TheyÔÇÖre both from deaf families, and technically they could both be considered deaf-of-deaf elite. But Cheyenna went to a mainstream school, which is why she has that kind of code-switching. She can switch to using more of her mouth when she signs, or signing more in English rather than ASL. That difference with Tessa, who lives 100 percent in an ASL world, would not be noticeable to the audience without deaf people behind the camera.

One other thing is that during the filming process, there are cast who might not be in the shot, who are having an outside conversation in sign. Having deaf people behind the camera, they can eavesdrop and say, ÔÇ£Oh they said something thatÔÇÖs really key that we need to get for this scene.ÔÇØ Hearing people wouldÔÇÖve missed so much of the nuance.

That was one of the most compelling elements to me ÔÇö some of the very small-scale demonstrations of how the world works differently for deaf people that I wouldÔÇÖve never thought about. Things like two college kids pointing out that when youÔÇÖre deaf, you canÔÇÖt make out and talk at the same time, because you need your hands for both activities. Or Alexa needing to sign something secretly, and moving her hands in front of her chest so that no one else could see what she was saying.┬á

We had a team during development that worked on something called ÔÇ£pods,ÔÇØ pieces of deaf culture and deaf behavior, without it being too obvious. We didnÔÇÖt want it to come off as preachy. So we went into the filming with that in mind.

What were the other pods?

You see one in the scene with Cheyenna and Renata when theyÔÇÖre sitting down and thereÔÇÖs a water bottle on the table in between them and they say, ÔÇ£This isnÔÇÖt deaf-friendly.ÔÇØ ThatÔÇÖs a pod, her having to move that bottle so they can see one anotherÔÇÖs signs. Another one was the furniture movement ÔÇö seeing everyone arrive at the beer garden, having to arrange the furniture without real regard to whom it might bother.

Another one ÔÇö itÔÇÖs very subtle, but to deaf people itÔÇÖs very clear ÔÇö is the bluntness within the deaf community. Sign language itself is a visual, direct language. It requires body language as well. ItÔÇÖs not like English where you can play around, beat around the bush a little with tone. Instead, deaf people come off as incredibly blunt.

So many more! When Daequan and Raelyn have a chance to chat through the window. And Braxton, while heÔÇÖs driving. So many times in my life, people have asked if I can drive. Can deaf people drive? And IÔÇÖm like, Really? So now I have a show with deaf people driving!