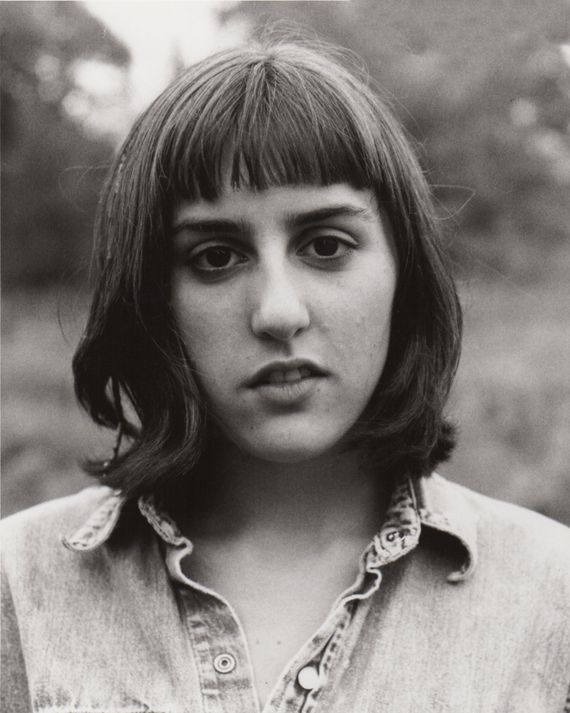

Filmmaker Ry Russo-Young has embraced the adage that artists must tell a story only they can tell. The 39-year-old director, known primarily for festival hits and teen dramas like Before I Fall and The Sun Is Also a Star, got very personal with her three-part HBO documentary, Nuclear Family, which aired its final episode Sunday.

Through interviews, reenactments, and home movies, Russo-Young examines the upper-middle-class New York childhood she enjoyed with her mothers, Sandy Russo and Robin Young, and older sister Cade ÔÇö and the potential unraveling of it all when Tom Steel, the man who provided the necessary sample for her DIY at-home fertilization, sued for paternity and visitation rights. (Cade had a different donor.) A near-stranger to Russo and Young before their daughterÔÇÖs conception, Steel would become a family friend who joined them on vacations and bonded with Ry and Cade. Then he brought on a major court case in the hopes of securing parental rights to Ry.

Coming at a time before same-sex marriage was legal, when homophobia and fears of the AIDS epidemic were rampant, the case could have forced the tween Russo-Young away from her family, as well as set a legal precedent that wouldÔÇÖve made it more difficult for same-sex couples or single parents to maintain custody of their children. In court, Steel and his lawyers used fear-mongering terms like ÔÇ£lesbian fusionÔÇØ (referring to an overt emotional intimacy in lesbian relationships) and tried to argue that biology holds more weight than upbringing. Though the courts ruled in favor of Russo-YoungÔÇÖs mothers and Steel ultimately dropped his appeal, the four-year case traumatized the family of four, particularly the daughters, who feared the only home they knew would be torn apart.

As the third episode explores, Steel was battling the AIDS-induced breakdown of his body as he battled Russo-YoungÔÇÖs mothers in court, and he died when she was a teen after attempting to reconcile with her. Now, following years of starts and stops documenting reactions to the ordeal, the filmmaker finally felt emotionally and professionally equipped to seek answers from those involved, including her parents and SteelÔÇÖs friends and family. In a recent phone conversation, Russo-Young discussed the challenge of turning the camera on herself, excavating painful memories, and whittling it all down to three episodes of TV.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

YouÔÇÖve made many fiction projects, but this is your first documentary project ÔÇö in more ways than one, as youÔÇÖve been working on it in one way or another for most of your life. How do you maintain objectivity as a filmmaker for a story thatÔÇÖs clearly so personal?

Part of it is that the medium of film really allows perspective, which is one of the reasons I wanted to make the series. IÔÇÖm still getting perspective on what I made by virtue of talking to someone whoÔÇÖs seen it and hearing how they process it and how it makes them think about their family. One of the amazing things about filmmaking is you can sit down and watch it over and over again. And you can see it differently and continue to understand it in a way thatÔÇÖs not myopic.

I started shooting around when I was 14, with a Hi8 camera. Did I know I was shooting this? No. But I started trying to tackle this topic, I would say earnestly, in college. I think IÔÇÖve waited this long to tell the story because I needed my craft to be at a certain level. I needed to have confidence in my ability to do it justice. The most significant thing is the deep understanding of storytelling and the rules of storytelling, so that I understand where I can depart from them and when I have to stick to them. Working in fiction so long really drove into me Joseph Campbell HeroÔÇÖs Journey ÔÇö the narrative arc payoffs. I think I was able to bring a lot of that narrative construction to this story. But I also was able to do it on my terms, which is actually more from my experimental roots: being able to go to history and then come back to the personal. For me, it took a certain amount of confidence in my own narratives and creative sense to be able to do that.

Was it hard to get your mind around the idea that you have to be the filmmaker and the subject?

I knew that was the big challenge. I was more uncomfortable being the subject. But the emotional stakes were so high in those situations when I was the subject that those took over more so than any kind of self-consciousness.

Up until the middle of the third episode, you are very angry with Tom and he is cast as a villain. And your parents remain angry with Tom. Why was it important to show a softening from your point of view?

The filmmaking desire to do it that way was because I wanted to mimic my narrative work in real life, chronologically ÔÇö which was that I was angry at him basically until my late teens, early 20s. My early 20s is when I started to wrestle with my feelings toward him in a more active way. But I hated him in the trial, and I hated him even when I was 16. I had a lot of venom, but it was starting to get more complicated. So I wanted the viewer, and the experience of watching the series, to mimic that arc.

One of the judges suggested in the footnote of his ruling that TomÔÇÖs diagnosis was motivating his quest for parental rights. Do you agree with that?┬á

Yes, absolutely.

Were there things you decided not to include?

Oh yeah. I wanted it to be a tightly braided narrative. And there were incredible pieces of the story that, for reasons that felt too tangential, ended up on the floor.

Can you tell me about some of them?

So Tom had a high-school girlfriend. He got her pregnant. They were both from Catholic families. She had the baby, and they put her up for adoption. The daughter had found me in my early 30s, and I went and I interviewed her. She had been looking for Tom her entire life, trying to figure out her birth parents. She had a very hard life growing up. She found him a year before he died, just after the lawsuit. Everyone said it was a really good time because he was suffering this loss from not being able to see me. And then he died. She was always sort of angry that she didnÔÇÖt get to spend more time with him.

We have a lot of physical similarities. SheÔÇÖs almost the inverse of me. WeÔÇÖre two sides of the same coin in some way. That was someone I thought was fascinating, but it felt like a narrative detour, so we couldnÔÇÖt include it.

Have you heard from her or any of TomÔÇÖs many siblings since this came out?

One of his siblings I interviewed, actually. And she didnÔÇÖt make it in either, which was a bummer. I heard from his daughter. But I havenÔÇÖt heard from the Steel family directly. They might be waiting, but I think they also need some time to process it. This isnÔÇÖt in the film, but he was the star of their family. He was the second oldest. In certain families, thereÔÇÖs a golden child, and he was that child.

The documentary discusses a time when Tom wanted to take you and Cade to a Steel family reunion, but heÔÇÖd told your moms that he wasnÔÇÖt sure how heÔÇÖd explain who you were. Were the Steels not aware of you?

My moms said that they werenÔÇÖt up at the time.

Was he out to his family?

Yes. IÔÇÖm not exactly sure when he came out to his family, but they knew he was gay. They knew his partner Milton, and he was part of their lives.

Milton wasnÔÇÖt interviewed for the documentary because he was battling AlzheimerÔÇÖs by the time you were ready to interview him. ItÔÇÖs also suggested in the documentary that he was a major influence on Tom and the lawsuit. Did you try to reach out to him earlier in your lives?┬á

No. I mean, I wasnÔÇÖt ready emotionally. I wish I had been. I did try to reach out to Milton, AlzheimerÔÇÖs and all. And what came back was he wasnÔÇÖt able to because of the AlzheimerÔÇÖs.

You also cast actors to reenact certain scenes from your childhood. That must have been one bizarre casting session.

It was definitely something I was really afraid of. We didnÔÇÖt do it until quite late in the game of making the series. We dropped them in and shot-listedÔÇöor outlined each sceneÔÇöshot-for-shot. That was certainly my narrative chops coming out. It was a crazy thing, casting myself at 9 years old and my mothers and all of them. And reliving those situations, or recreating them.

Other people have done that before. Sarah Polley famously used the technique as a sleight-of-hand in Stories We Tell, a film about her complicated parentage. Were you cognizant of that and trying not to look like something she did?

Well, I think her movie was really different. One of the big things there was the premise of those being home movies, and then she recreated them. I wasnÔÇÖt worried about copying. The fear was that I didnÔÇÖt want to fall into the negative tropes of the genre, like making an autobiography documentary or being self-indulgent and navel-gazing.

You also make a point of devoting some of the series to how this trial, and the battle over your love, affected your sister Cade. The familyÔÇÖs relationship with her donor was more distant.

Yeah, I mean, talking about things on the cutting-room floor, I think we could make an entire three-part documentary about Cade and her experience with her donor and her journey.

In the trial, there was so much emphasis on me. But it was something that we were going through as a family. And it affected everyone in the family in different ways and in similar ways. And I felt it was absolutely critical to make that clear ÔÇö that it was happening to all of us ÔÇö and to show the pain that was inflicted upon her. It was also important because our whole lives, we were having to prove that we were sisters.

What happened to CadeÔÇÖs donor? ItÔÇÖs said in the documentary that he was an alcoholic and he was asked not to interact with you and your sister anymore. But was he part of the trial?

He died of AIDS around the same time that Tom died. In terms of the role that he refused to play in the lawsuit: He wouldnÔÇÖt testify for us; he wouldnÔÇÖt testify for Tom. He remained, quote-unquote, agnostic. And that was really hurtful to my sister. And she felt betrayed by him.

As you grew older, you and your family appeared on talk shows and did interviews to talk about the case. Footage in Nuclear Family shows that not all audience members were welcoming. Do you regret doing those interviews now?

I donÔÇÖt. But IÔÇÖm not big on regret overall. I think my philosophy is that life choices either kill you or make you stronger. And it wouldnÔÇÖt be in this series if I hadnÔÇÖt done it. And it was something that I wanted to do, so I donÔÇÖt regret it. ItÔÇÖs crazy to look at now, but IÔÇÖm not sorry.

You also interview Chris, the woman who was a close friend of your parents and who introduced them to Tom. Your parents felt she took TomÔÇÖs side during the trial and they stopped speaking. WhatÔÇÖs their relationship like now?

There isnÔÇÖt one. It was hard to go talk to her, certainly in the beginning, because I knew that my moms would feel threatened by it, and I didnÔÇÖt want to hurt my moms and I didnÔÇÖt want them to feel betrayed. So that was tough to navigate. And it was hard to process everything Chris told me and try to find my own truth in it all.

Is it hard for you to find the right language in regard to the titles you give to some of the people ÔÇö brothers, sisters, cousins, etc. ÔÇö in your life?

The only one thatÔÇÖs really difficult is Tom, actually. I think everyone else is very clear for me, or somewhat clear. Tom IÔÇÖve always wrestled with. I was talking about this yesterday with another ÔÇ£queer spawnÔÇØ ÔÇö another kid I know who grew up with lesbian moms. And she was saying that she calls her sperm donor her ÔÇ£donor fatherÔÇØ; that was the most comfortable word for her. And for me, IÔÇÖm not really comfortable with any language. ÔÇ£Biological fatherÔÇØ actually feels closer to me because ÔÇ£sperm donorÔÇØ feels too impersonal. I would never call him my dad or my father, but IÔÇÖve always wrestled with the correct language because IÔÇÖve wrestled with where he sits in my life and my heart.