This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

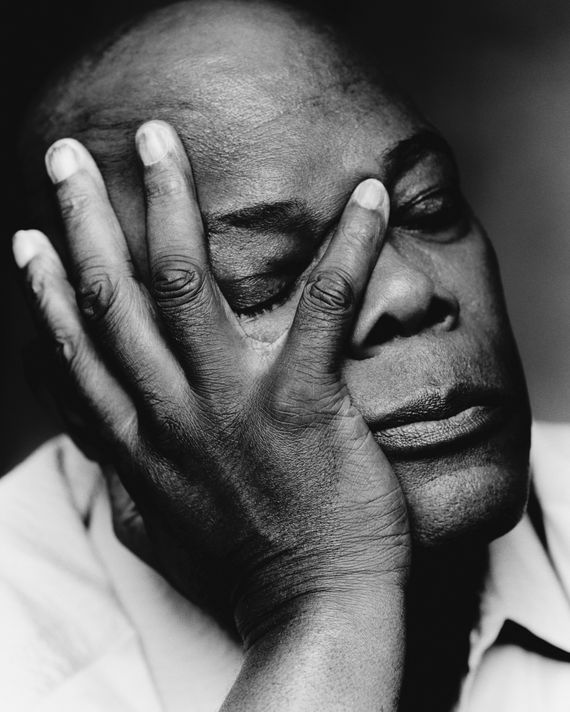

Think about some of these iconic movie lines: “I’ve had it with these motherfucking snakes on this motherfucking plane!” “What the fuck happened to you, man? Shit, your ass used to be beautiful!” “And that’s the truth, Ruth.” “Yes, they deserved to die, and I hope they burn in hell!” “Hold on to your butts.” “And you will know my name is the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon thee.” The words are the work of writers. But none of these quotes would have become part of our pop-culture lexicon if it weren’t for Samuel L. Jackson’s authoritative, impassioned delivery.

The 74-year-old actor, probably the most bankable movie star of our time, is a major part of multiple franchises: the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Star Wars universe, the MonsterVerse, the Shaft-verse, the Kingsman-verse, the Unbreakable-verse, the Tarantino-verse. Jackson loves making popcorn flicks. And to hear him talk about Secret Invasion, the new Disney+ Marvel series that follows former Avengers honcho Nick Fury (whom he has been playing since 2008’s Iron Man), it’s clear he has thought long and hard about how to ground the character in something resembling reality, no matter how fantastical the story.

The breadth of Jackson’s screen and stage roles remains astonishing. He was raised in segregated Chattanooga, Tennessee, and started in the business alternating between serious work and pure entertainment. In many ways, he hasn’t really stopped, even as the industry has gone all-in on the kinds of blockbusters he regularly stars in. What comes through from watching him, and talking to him, is his profound love and respect for the craft of acting.

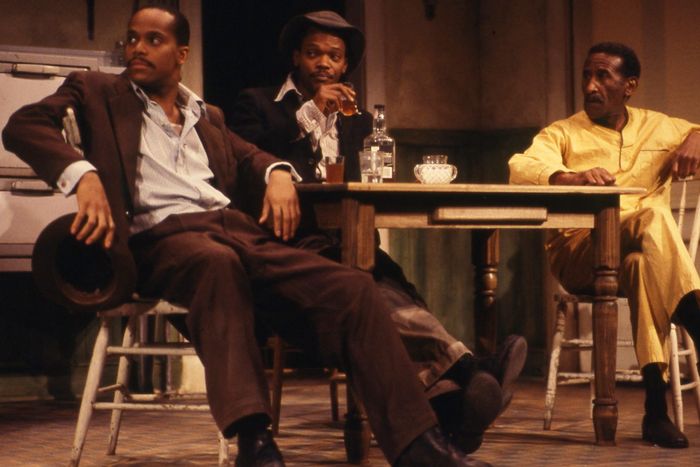

I saw you in The Piano Lesson in October. You were in the original Yale Rep production back in 1987, playing Boy Willie. What was it like to return to this play as Boy Willie’s uncle?

Different. First of all, my wife, LaTanya, was directing it. I didn’t have the responsibility of being the engine that runs the play just being a supporting character. I was more or less a moderator, which was fine.

She had seen the original production in which you starred. Was this a project she’d been thinking about for a while?

Not to my knowledge. She and Denzel Washington are really close. He had the responsibility of putting all those August Wilson plays on film. His son John David wanted to do a play; Denzel figured that was a good place for him to start. Boy Willie is tough! Especially if you’ve never been onstage before. She did a huge job teaching him stagecraft. I just learned to do like I always do: Take a note; don’t say anything. She gave me one note: DO NOT TALK TO JOHN DAVID ABOUT BOY WILLIE. So I didn’t. She didn’t want me telling him who I thought Boy Willie was so he could form his own character. Because my Boy Willie would be informed by Lloyd Richards’s directing. August was still writing the play when I did it. By the time it got to Broadway, it was very different than the play I did at Yale.

That was a pretty long period early in your career when you were doing stage.

Yeah, quite a long period. My wife and I moved to New York on Halloween Night 1976. We drove right into the middle of that parade ’cause we were going to stay with some friends down in the Village. It was a great time to be an actor or be a Black actor in New York. I mean, Joe Papp had the Black-Hispanic Shakespeare Company, and Negro Ensemble Company was bustling. Billie Holiday Theatre, Henry Street theater. The Frank Silvera Writers’ Workshop was going on. And there was a really, really great group of actors running around there that we either worked together, auditioned together, or went to see each other work all the time. I was there when Morgan Freeman got plucked out of the theater world. And Wesley Snipes and Laurence Fishburne. I remember auditioning for Platoon, but Keith David used to always get all the jobs everybody wanted.

I don’t know how young people are in New York now, but we were a very big family. If I went to an audition that I knew I wasn’t going to get, I could always call somebody I knew that was better for it. It wasn’t a dog-eat-dog world. It was a very, very sharing and communal world.

I imagine all that time onstage helped shape the kind of actor you are now.

Totally. I was taught that if my character’s background is not there, give him one. How far in school did he go? Has he been in the military? Has he been in jail?

Even now, with Nick Fury, he had a whole other life that we hadn’t dealt with. Having the theatrical background allows me to imagine what nobody’s ever seen on film. And whether I talk about it or not, I carry that information around with me; I know who that person is or what their history is. When I hit the screen, a lot of times audience members go, I want to go with him. Because I’ve got something interesting happening in my body language or how I present myself. All those things I learned to do when I was on the stage.

It’s fascinating reading about how Marvel projects are planned out years in advance and the kind of control that Kevin Feige and other executives exert over what happens to these characters. After a point, do you get to have more input because you’ve been Nick Fury for so long?

Well, no. Or you would’ve seen my ass in Wakanda.

Why are you not in Wakanda?

I don’t know! I asked many times, “When do I get to go to Wakanda?” And they’re like, “No.” “Why? I know Wakanda is there. And I know about T’Challa. Why do I never encounter them?”

What’d they say?

They were like, “We’ll see.” Don Cheadle and Anthony Mackie — all the Black people in the Marvel universe are like, “Wakanda. Do we get to chill in Wakanda?” Until Tony Stark’s funeral. That’s the only time you’ve seen Nick Fury and all those guys around each other at one time.

Your presence gave a gravity and a legitimacy to the MCU in its early stages. I remember how excited people got when Nick Fury showed up. You arrive in these movies and it’s kind of like, Okay. This is real.

Better me than David Hasselhoff — is that what you’re saying? He’s still a little testy about that.

Did you see his Nick Fury? I haven’t.

Yeah. It was all right. It wasn’t what I knew.

Nowadays, what does it take to get you really excited about a role? And has that changed over the years?

I don’t think so. I still get excited by action pictures or things that pique my sense of humor. Even though I like a serious movie. But I’m still looking for those movies that I like to watch over and over again. I still got that kind of thing with me — when I go outdoors to play, I want to play with people that are cool. Even in Secret Invasion, with Olivia Colman, when I walked in that room and she was there, we both just looked at each other and started laughing: This is going to be that kind of day. This is going to be a great day. And it was.

There’s no other reason to do something like the Hitman’s Bodyguard other than wanting to be in that space with somebody like Ryan Reynolds, who’s just an enormous amount of fun to be with. I don’t think the Hitman’s Bodyguard is an A-list movie in anybody’s category. But I also know that if it’s me and Ryan and we’re having a good fucking time, a lot of people are going to watch it and they’re going to be like, This is fucking great. We changed the tone of that material because we did it.

Ryan is a savvy motherfucker. I knew him from when he and Scarlett Johansson got married. My wedding gift to them was a beehive. Scarlett was always talking about nature. So I had my assistant go out and buy 10 pounds of bees and then I bought them bee suits and the whole thing. They kept bees for a while. They got honey for a couple of years while they were married. And then one day the bees abandoned the hive or they abandoned the queen or some shit.

Do you still find yourself learning things from other actors?

Sure. Like you said, my theater training has me in a kind of thing. I’m on time. When they call me, I go to set. I hit my marks. I know my lines. Know most of everybody else’s lines. Sometimes you’re doing a scene with an actor and it’s like, How many different ways is this motherfucker going to do this shit? Take two comes and they do some other shit. And take three comes and they try some other shit. It’s like, “Why you keep trying shit? Do you not know what you’re going to do?” Because I know from page one to page 151 what I’m going to do in this movie. Sometimes directors will go, “Well, you do it your way and then do one my way.” And I go, “I don’t get to go to the editing room. And the thing that you like is the thing that you’re going to look at first. You may never look at my thing again. So let’s not do that.”

Making movies is less an actor’s medium than a director’s medium. And directors are generally the person on the movie set with the least amount of experience. A lot of times, they don’t know specifically what’s happening. Especially some directors these days — they’re doing frame composition and they forget about the story. In my opinion, the worst thing that happened to movie making is people stopped making movies on film. ‘Cause young directors have no idea how much it cost to make a movie. You had to process the film. You had to watch dailies, you had to hope it’s in focus. Sometimes you had rollouts; you had to stop, wait, change. Young directors don’t know anything about any of the things that it takes to make a movie that used to be part of the skill of making it. So they do take, after take, after take, after take, after take, after take, after take.

But somebody’s got to take care of the words and intentions. I say sometimes I was cursed by making Hollywood films with people like John Frankenheimer and Billy Friedkin, guys who knew what they were doing. And they would say, “If you ever direct, don’t put anything in your movie you don’t want in it because the studio will find that piece of footage and they’ll go in there and they’ll change your shit.” And they’d say, “And with you, don’t do anything you don’t want to see in the movie.” So I learned not to temper my performance but to hold on to specific things that can’t be excised. Because I don’t give you a choice to excise it. It’s me protecting not just me but the character and the integrity of the story the way I saw it when I read it.

You’ve done so many movies that there must have been ones where the movie you saw in your head was not the movie that wound up onscreen.

Of course. Those were early films. In A Time to Kill, when I kill those guys, I kill them because my daughter needs to know that those guys are not on the planet anymore and they will never hurt her again — that I will do anything to protect her. That’s how I played that character throughout. And there were specific things we shot, things I did to make sure that she understood that, but in the editing process, they got taken out. And it looked like I killed those dudes and then planned every move to make sure that I was going to get away with it. When I saw it, I was sitting there like, What the fuck?

But also the things they took out kept me from getting an Oscar. Really, motherfuckers? You just took that shit from me? My first day working on that film, I did a speech in a room with an actor and the whole fucking set was in tears when I finished. I was like, Okay. I’m on the right page. That shit is not in the movie! And I know why it’s not. Because it wasn’t my movie, and they weren’t trying to make me a star. That was one of the first times that I saw that shit happen. There are things that I’ve done in other movies where I said, “Wait a minute. Why did you take that moment out of the movie?” Because the moment, in that movie, it’s bigger than the movie.

It sounds like a lot of this is from that immediate period post–Jungle Fever, when you were getting studio deals and stuff like that.

Jungle Fever got me into Hollywood. The majority of Black people in America at that time, at a certain economic strata, had a Gator in their family.

You had yourself just come out of rehab at the time you did that part, right?

Yeah. I got there and Spike Lee started talking to me about Gator. In his mind, I was always high when I showed up in the movie. I told Spike, “Look, the worst thing about the crack epidemic is the fracture of the family and how crack addicts ruin their relationships with everybody.” ‘Cause I had fucked up my relationships with most of the people I knew. I told Spike I would much rather deal with the erosion of the relationships. So when I see them, I don’t want to be high. When I see them, I want to be trying to get something from them. He’s like, “Oh, okay.” We end up having dueling crackheads that summer, ‘cause New Jack City was out. So you got Chris Rock doing Pookie, being high and whatever all the time. And you got me being Gator who people were looking at going, Oh shit, that’s my cousin, that’s my uncle, that’s my son, that’s my nephew, my husband.

But you were clean by that point, right?

I was clean, but I was still detoxing. I had done my 28 days. When I got to set, I really didn’t need makeup. The first day I was on set, I was going to craft service, and the Fruit of Islam who were guarding the set were trying to run me out ‘cause they thought I was a neighborhood crackhead.

Is that the biggest part you’ve done for Spike Lee?

I guess, yeah. Mister Señor Love Daddy wasn’t a small part, but he was kind of isolated there in that booth. I’m always sitting in there looking out the window like, Shit I want to be out there. I didn’t do that much in Mo’ Better except break Spike’s bones and ruin Denzel’s trumpet playing career. School Daze was very small. So yeah, that was the most significant Spike Lee part I’ve had.

What did you guys fall out over?

Over Malcolm X. I actually read with most of the people who auditioned for Malcolm X. I was supposed to be the guy that turned Malcolm X on to Islam in prison. I forget who played that role. But it was still down to that Spike Lee scale-plus-10 salary thing. I was like, “I’m not going to work for no scale-plus-10. “

I used to call my agent every day to see if I had any auditions, callbacks, whatever. And my line to her every day was, “Hollywood call?” She was like, “No, sir.” So one day I called, she said, “As a matter of fact, yeah they did. You just won an award at the Cannes Film Festival.” And I’m like, “What? For what?” She said, “Jungle Fever.” I said, “They don’t give supporting actor awards at Cannes.” She’s like, “They made up one for you.” “Get the fuck out of here!” “And consequently, these people in Hollywood want to see you for this movie White Sands.” So I took White Sands instead of Malcolm X and we fell out.

White Sands is a part where, early on, we don’t know how big your character’s going to be, but you command the screen in such a way that it’s almost obvious from the get-go that you’re going to turn out to be the bad guy. Because there’s no way they’re going to cast you to come on and just give a few lines of instruction.

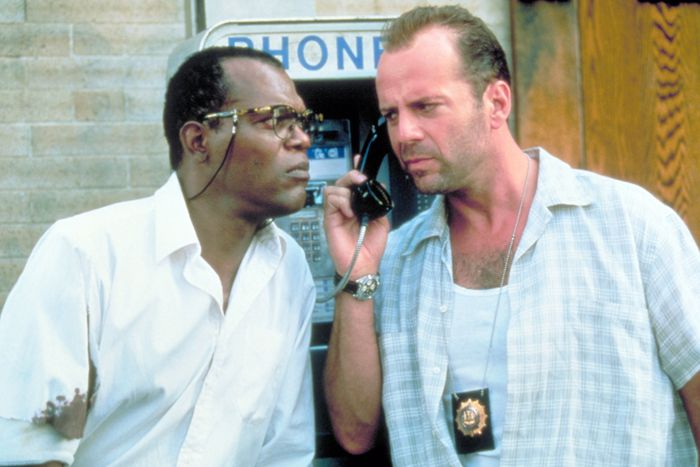

Well, nobody knew who I was at that time. I went from there to this Nic Cage movie, Kiss of Death. One day, these guys come to set and they go, “Any interest in being in Die Hard With a Vengeance?” And I was like, “Yeah. But I’m waiting to hear about Waterworld,” which I’d auditioned for. And they say, “Someone already has that job.” I was like, “What? How do you know?” They’re like, “Believe me — you’re not getting that job.” I’m like, “Oh, shit. Die Hard. You think I can get a bigger room at the Chateau Marmont?” And they were like, “Yeah.” So I called my agents and told them, “I told these guys I would do Die Hard.” And they were like, “You made a deal?” I said, “I didn’t make a deal. I just asked for a bigger room if I’m going to stay here.” And so I ended up getting Die Hard. I had done Pulp Fiction. I had to do that fucking acting contest to get in Pulp, even though they told me I had the job.

Wait, tell me about the acting contest.

I was doing Fresh for Lawrence Bender, who was the producer of Pulp. Quentin sent me the script, told me, “Jules is yours.” I went in and they just wanted to hear the character. I read it, and they were like, “Amazing. Job’s yours.” I come to New York, do Fresh. Then I hear, “Well, there’s this other actor who came in to audition for Pulp for another role, and he asked if he could read Jules, and we let him. And we kind of love him. So we need you to come back and read it again.” Now I’m like, “What the fuck? What do you mean, read again?” My agent’s managers call Harvey, they’re cursing him out. And Harvey’s like, “Look, Sam’s got the job. We just need him to come in, do it. Blah, blah blah.”

I shoot Fresh on a Saturday and I got on a plane that night, take the red-eye to LA. And I’m on the plane doing all the shit that I normally do when I get ready to do a job. I’m breaking down the fucking role. I’m breaking down the sentences. By the time I get there, they’re not even there. They’ve gone to lunch or some shit. They come back and everybody’s like, “Hey, Sam.” And some dude, the last dude that came in, right behind me. He was going, “Hi. Mr. Fishburne. Glad to meet you.” I was like, “What the fuck? Who is this motherfucker?”

Well, I go in the room and we’re doing the scene. And the first thing we’re doing is the killing room scene: “Do you speak English? English, motherfucker, do you speak it?” And he’s so busy watching me, he gets lost in the fucking dialogue. And I’m like, “What the fuck? You’re fucking up my audition here!” I want to slap him. By the time we finish and we do the end scene in the diner where I do the last scene, me and Tim Roth, they were like, “Thanks. Blah, blah, blah.” I slammed the script down. I slam the door and leave. Go back to the airport, because I had to work Monday, come back to New York. Then I see Bender. And he’s like, “We were so going to cast this other kid until you did that last speech in the diner. ” And I was like, “Really, motherfucker? So I had to go through all that, after you told me I had a job?”

Who was the other actor?

Kid named Paul Calderon. Good actor from New York. But anyhow, what I’m saying is I did Pulp and then Kiss of Death. And we’re doing Die Hard: With a Vengeance. And in the middle of Die Hard Cannes happens. I fly to Cannes with Bruce for the premiere of Pulp Fiction, it’s one of my first times on private planes. And Bruce was like, “Yeah. This movie’s going to be great for you. But Die Hard’s going to make you a star.” And sure enough, Pulp comes out, it’s great, people love it. But Die Hard next year is the highest grossing movie worldwide. All of a sudden I’m an international motherfucker.

And then the whole Oscar fiasco happened with Harvey manipulation of that whole thing: “Well, you and John will cancel each other out, so we’re going to put him in a lead actor and you in supporting actor. You got a better shot.” And then the whole award season, everybody’s telling me about the winner. “Well, you know Martin’s been nominated four times. Your time’s coming.” “Wait a minute. I lost already? What the fuck? What are you telling me?” I thought it was based on what we just did, not the fact that you’ve been nominated how many times. Sure enough. I lost all the time. All the time. I lost the Globes. I lost this. I lost that. And then the night that you’re sitting there at the Oscars, you sit there and go, I lost every time. Maybe they get it right this time. And they didn’t. I think I’m the only person that’s ever said “Shit” in the middle of the little square on the TV.

I think Martin Landau won for Ed Wood, right? Which is a really good movie.

Who saw it? [Laughs]

It seems like you had a similar moment again on the Tonys recently. Some people complained that you were frowning.

Yeah, that’s just some bullshit. Actually my face was more like, hmmm. [Makes an impressed expression.] I expected that kid to win. Why wouldn’t I expect him to win? It’s fine. I had no expectation of going to that event and winning an award. I don’t need an EGOT. I’m good. It’s not going to move the comma on my check.

Are you planning on being in Tarantino’s next film, The Movie Critic? Have you talked to him about that at all?

No comment. [Laughs]

I hope you are, if it’s going to be his last movie, because I feel like you guys came up together in a way.

Feels like it. But when I saw Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, I mean, how many Black people are in that movie? Maybe three. It was kind of like watching Goodfellas. When I was in Goodfellas, it’s like me and somebody else.

Did you tell that to Tarantino?

No. I’ve only seen him once since the movie came out and that was at my Oscar ceremony. He came to that. That’s the only time I’ve seen him and I wasn’t going to talk about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood that night.

How did it feel getting the Honorary Oscar?

Didn’t feel honorary, just felt like I was getting an Oscar. I earned it. I worked for it. I can possibly name four other instances where I could have won or should have won or should have been nominated, but I’m fine with it. It’s mine. I got it. My name’s on it.

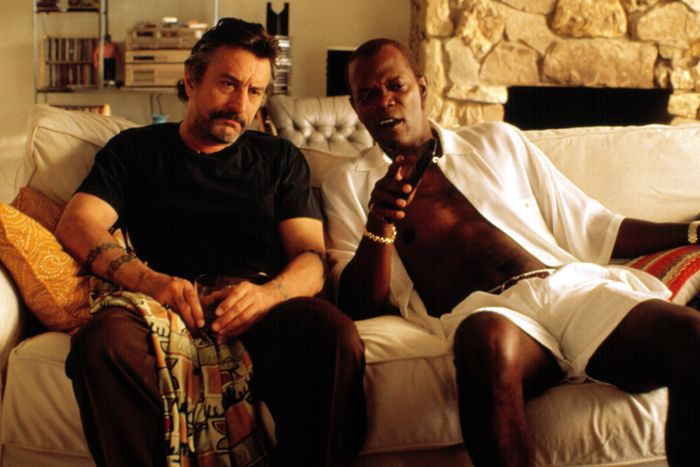

Would you consider Jackie Brown one of those films?

Of course. Ordell’s one of my favorite characters. Yeah.

I remember when Jackie Brown came out, it didn’t make as much money as Pulp Fiction, so people saw it as a disappointment.

The problem is, it wasn’t Pulp Fiction 2. It was a great movie. Possibly a better movie. But it wasn’t Pulp Fiction 2. That’s what people wanted, until they realized, Okay, this guy has other ideas about what he wants to do. That didn’t happen until Kill Bill. I watched a lot of kung videos back in the day when I’d be in my trailer. Tarantino would pop in. I had this place that used to sell three kung fu movies for $5. Just off Times Square, right across from the bus station.

Was this the 43rd Chamber, which later moved from 42nd to 43rd street? There was a small room, and a guy behind the counter. You’d go there and they’d even let you watch some of the movie on a small TV, so you could see the quality of the dub.

Yeah, I went in there a lot. They also had those theaters on 42nd Street where you could watch three kung-fu movies for a dollar. So I spent a lot of time in those places all day long. But yeah, and a lot of Shaw Brothers. [Mimics the Shaw Bros. intro music] Yeah!

You’ve said that when you did that final speech in Pulp Fiction during your audition, it’s what secured you the role. That brings to mind something that maybe an older generation of actors pays attention to in a way that younger generations don’t: the quality of voice. Not just reading the lines but the sense that your voice is something unique and powerful.

I grew up in a house where we didn’t have a TV for a very long time. And I was listening to radio dramas with my grandfather. I heard stories, and I had to see the pictures in my head. Andy Griffith was an amazing storyteller. I would listen to Sergeant Preston of the Yukon or Gang Busters or Amos ’n Andy. I was blessed to grab hold of it and understand it; I learned how to use my voice. When I want you to feel a certain way, I know to take my voice here. When I want to pull you along with me, I know to talk a little faster to get you to do it. Even if you don’t see me, you are in the story. I can put you in it. I can make you cold. I can make you hot. I can do things to you with my voice. It’s an important tool that I don’t think they teach. Now, you got your mics in your wigs and shit.

But when I came through, man, every director I had used to sit in the back of the theater in the dark during rehearsal to make you talk to him. You spoke a certain way during the play. Then when you wanted them to get a point, you had to make them sit forward. It’s part of the control that the actor has over the audience. We had actors, even in The Piano Lesson, that would say, “Well, the audience is going to dictate how we do the play.” My wife was like, “Oh, fuck no. The audience does not take control of my play. You are in control of the audience; the audience is not in control of you.” That’s when you see actors do things — like when they fall in love with a laugh. And if that laugh doesn’t come, they get thrown.

Who were the early TV and movie actors that you gravitated to?

We only had three channels, so we didn’t have a lot to choose from. I learned to appreciate things like Jack Webb and Dragnet and George Reeves’s Superman. There was a whole cowboy culture then. I had the Have Gun — Will Travel pistol set cards. And Steve McQueen on Wanted Dead or Alive. Those were the cool TV cowboys. Clint Eastwood, Rawhide. Naturally, Wagon Train was on so I watched that, trying to figure out how long it was going to take these people to go from wherever the hell they started to get to California. Every year it’s like, So what happens when they get to the mountains and it snows? And I read too much to not know that they were only going 10, 15 miles a day at best.

Then all of a sudden there were things like Man from U.N.C.L.E. So all of a sudden you wanted to be a spy. Or I Spy with Bill Cosby. Naturally we watched that ‘cause he was one of the Black people on TV. I watched all the comedy stuff that was on. Red Skelton, Jackie Gleason, Jack Benny. Ed Sullivan exposed me to a lot of things that I naturally didn’t see in Tennessee. Borscht Belt comedy, Broadway singers, different comedy acts, or international shit like Señor Wences. It was more entertainment than wish fulfillment. Watching 77 Sunset Strip, everybody wanted to be Kookie but once I got to California in sixth grade, I saw the Sunset Strip, and it was like, “Oh, this is what this is.” I was more interested in being Errol Flynn with a sword in my hand than anybody I saw on TV except cowboys.

And then war stuff, John Wayne movies or the TV show Combat when Vic Morrow was on there. Oh, and I liked Lee Marvin a lot too. M Squad. The gritty people.

I wonder if there’s a connection with these shows and the popcorn movies you still love to do, because this was the stuff you grew up on.

The monster movies, I saw pretty much all of them. I Married a Monster from Outer Space or Creature from the Black Lagoon, lots of Dracula, Frankenstein, The Blob. And the Japanese movies, the Godzillas and the Mothras and all those things. Everybody wants to run from a monster. So I end up doing something like Deep Blue Sea ‘cause it was like, “Okay, I’m running from a monster. It’s a big ass shark, but I’m running from it.” When I heard about Snakes on a Plane, I had just done Formula 51 with the director. So I called him, was like, “Are you going to do a movie called Snakes on a Plane? Is it what I think it is?” He’s like, “Yes, it’s a plane full of poisonous snakes turned loose.” I’m like, “Oh shit, can I be in that?” So he called New Line, New Line was excited. I signed on and then I don’t know what happened. In the midst of all that, the director got fired. I was like, “Oh, well I’m still going to do it. Fuck that.” When I got there, they were trying to change the name of it to something like Pacific Flight 121, “‘Cause we don’t want to give it away.” I was like, “That’s exactly what you want to do! Hell is wrong with you? I signed up for Snakes on a Plane and I guarantee you that audiences will be way more excited about Snakes on a Plane than Pacific Flight 121.”

You’ve talked in the past about how your aunt first had you acting when you were basically a toddler. But was there a conscious point at which you thought, “Oh, I can do this. I can be an actor.”

In college, I was taking this public speaking class. The professor was directing the Threepenny Opera and didn’t have enough guys auditioning. He was like, “Any of you guys want to be in the play? I give extra credit for class.” I rolled over there that night, and I guess they were doing some photo session for the whorehouse in the Threepenny Opera, which I didn’t realize was happening. All these girls in corsets and garter belts and shit. And I was like, “Okay. This could be a good place. This could be the spot!” [Laughs] Everything changed.

Then, Blaxploitation started to happen. I’m like, “Oh, wait a minute.” Because for a while there was Sidney, Harry, James Earl Jones. Not a lot of other people. Moses Gunn. And then all of a sudden Jim Brown and Fred Williamson and all those guys started doing movies, “Okay. We’re opening up here. We got cowboy pictures. We got gangster pictures. And a couple of love stories, the Jane Pittmans and all those things.” I remember auditioning for things like Roots and stuff like that.

When I finally told my mom, “I think I’m going to be an actor,” she’s like, “So what are you going to do for a living?” It’s like, “I’m going to be an actor.” That doesn’t make sense until they see you on TV or somewhere. I finally did a commercial for Krystal Hamburgers and all her friends said, “I saw Sam on TV.” “Oh, yes. He’s an actor.” But as a viable career, not till the ‘60s.

You went to Morehouse, and I believe it was during college that you became more politically active. You were an usher at Martin Luther King, Jr.’s funeral. How did your activism first start?

I guess it happened when I was a freshman in college in the fall of ‘66. I have a cousin who’s the same age as I am. He went to the army, I went to college. Three months later, he was dead, walking point in Vietnam. And I met the first guys at Morehouse, these dudes with afros and fists made out of jump cord and all this other stuff, telling us that if we didn’t stay in school, we were going to end up in the war and we’re going to be dead. And we’re like, “What fucking war?” So that’s when I started paying attention to the war. The civil rights movement was already happening. I was already connecting with people like Stokely Carmichael and Rap Brown and those guys, and not specifically wanting to be part of Dr. King’s movement. I wasn’t going to sit on some lunch counter and let somebody spit on me, hit me and do that shit. I was not a nonviolent protester.

So that was the beginning, basically, of my activism. Being a certain age and looking at the world and identifying it for what it is and what it becomes, which is why as soon as I hear “Make America Great Again,” I go, “When are we talking about again? Are we talking about back when we had apartheid?” I grew up in segregation in Tennessee. I went to school with Black kids ‘cause we couldn’t go to school with white kids. I saw Klan marches and Klan rallies. So I know what America used to be. When I hear them say, “Let’s make it that again,” it just makes my blood boil.

I’m 74. I don’t know how much longer I’m going to be around here raising hell or doing what I’m doing. But people need to start understanding that the economic gap is crazy. I pay an enormous amount of taxes, and it’s fine because I know I should. But why can’t we get billionaires to pay their fucking taxes? If those motherfuckers paid their taxes we’d solve a whole bunch of shit. And they would still be richer than every motherfucker walking around them.

In 1969, you got kicked out of school after you and some fellow students locked in the Morehouse board when they refused to meet with you guys. What happened after that?

I got kicked out of school and I came to LA! Yeah. I had some trouble with some civil rights stuff in Atlanta, so I had to get out of town.

The FBI called your house, as I understand.

They kind of showed up on the door. Told my mom, get my ass out of Atlanta before I got shot. They scared her enough for her to get me out. She said, “You want to go to lunch?” I got in the car with her and she gave me a plane ticket and said, “You’re going to LA.” She took me to the airport, and then she said, “I’ll get all your shit.” And they cleaned out all my shit and sent it to me.

You arrive in LA, what do you do?

I didn’t know anything about the business or LA or anything. I didn’t have a car. I rode the bus for a while back and forth. And then I finally got a job. I worked for the bureau of public assistance. I assessed people who were on public assistance. I used to go to people’s houses and see if they were still eligible. I wouldn’t have taken anybody’s fucking money. I was still part of the Black Revolution then. All these people that were on welfare, I just went out and sat in their house, smoked reefer with them, and hung out, made sure that all this stuff was in order and made sure they stayed on public assistance.

After Pulp Fiction and Die Hard With a Vengeance, you basically become a household name. But I’ve noticed that you’d still do supporting parts. It didn’t seem like you always had to be the lead. Was it the fact that you had spent so much time getting to that point that you just wanted to keep working?

I am a firm believer of that bullshit that they used to tell us, “There are no small parts, only small actors.” I just show up. Sometimes I show up uncredited. Sometimes it’s a favor, or I’m doing it because I actually think that this director is going to do something later and I want to be part of that director’s lexicon. I used to fight all the time with my agents. When I first got to Hollywood, there was a stigma. You don’t do television. You’re a movie star. You don’t do TV. I said, “No. I’m an actor.” “No. You’re a movie star.” I said, “But I want to be on this.” “No. People don’t pay their money to go to the movies to see people they see every day or every week for free.” “The fuck are you talking about? It’s acting.” That didn’t change until like HBO or some shit came along. All of a sudden it’s like, “Well, they’re paying to watch TV now, so you can do some of that.” I said, “I don’t want to be on any of those.”

Fortunately I’ve been in the blockbuster business for a while. I remember I was on some British talk show and they asked me if there were any directors I wanted to work with I hadn’t worked with. I go, “Yeah, George Lucas. I’d love to be in a Star Wars movie.” Then I go off and I’m doing Sphere in Vallejo with Dustin and Sharon Stone and I get a call. “George Lucas would like to meet you. He hears you want to be in his Star Wars movie.” Then George and I became really good friends. He liked my work ethic, he liked the fact I showed up, I hit my marks, I knew my lines, I was nice to everybody, I was cool, I was glad to be there. So now I’m in the Star Wars universe, which is great. Back then, that was the biggest fan base on the planet. I’ve been accosted by the Jedi Council of every city on the planet. “Master Windu, please, let us have a council.” “Get away from my room!” They’re outside in the parking lot, chanting. Jesus, these people are adults. Stop it.

The idea of there not being any small parts — I think some movies have used that aspect of your persona really well, like Deep Blue Sea. You’re one of the bigger names in the cast, so it’s a real surprise when you get eaten so early.

I was in that movie way longer than I intended to be. Because Renny Harlin told me, “You are going to be the first person to die, which means anybody can die.” I was like, “Okay.” I thought I was going to show up. The shark was going to show up. I was going to get killed in the movie. And next thing I know, I’m soaking wet for a month and a half in Mexico. “What the fuck, man? When am I going to die?”

Renny Harlin had also used you really well in The Long Kiss Goodnight earlier.

I read Long Kiss and I kept asking my people to get me in to read for this role. But the studio was like, “No.” “Man, what the fuck?” They wouldn’t see me. And I went to a party somewhere. Renny and Geena Davis were there. I said to Renny, “Hey man, why won’t you let me read for your movie?” He’s like, “Let you read for my movie?” I said, “Yeah. The Long Kiss Goodnight, they won’t let me come in.” He said, “You want be in the movie?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “You’re in the movie.” “The fuck out of here. Really?” And sure enough, next week I was in the movie. I never auditioned, never read, never did anything.

Why didn’t they want you for the movie?

Because there was a greater romantic thing happening between Mitch and Charly Baltimore. He literally fucked her in the first script. Or she fucked him. She gets off of that wheel, after killing that dude, and she finds me down in that basement and I’m freezing. In the original script, she strips herself naked and wraps herself around me.

Long Kiss is an awesome movie. And I still love Mitch Hennessy. I’d do a Mitch Hennessy movie in a minute. Maybe the daughter grows up and she wants to know more about her mom and she takes on the whole mantle of who Charly Baltimore was.

Why not? They did another Top Gun.

Come find Mitch. Come find Mitch Hennessy!

What are some other films along the way that didn’t get the reception you’d hoped for, that you wish you could get people to watch again?

One Eight Seven, for sure. One Eight Seven was a serious subject that got kicked to the curb for some reason. I remember they were trying to get us on Oprah to talk about the plight of teachers in schools. And she was busy promoting Beloved, so she wouldn’t. “I don’t do violence on my shows.” I said, “Bitch, you just killed your goddamn daughter in your own room. The fuck you talking about? Give me a break.” And now prophetically teachers are getting jacked in schools every day. This movie spoke directly to that. People are looking at Eve’s Bayou differently now. And The Caveman’s Valentine is interesting. I don’t know, man. I just do the movies. Shit.

More Conversations

- David Lynch on His Memoir Room to Dream and Clues to His Films

- Willem Dafoe on the Art of Surrender

- Emily Watson: ‘I’m Blessed With a Readable Face’