In June 2012, shortly after stepping down as president of IFC TV and Sundance Channel, then-45-year-old Evan Shapiro published a manifesto. It was an intervention for TV in the early days of the streaming wars, before your Pluses and Maxes and Quibis (RIP). Shapiro warned of the havoc millennial “cord-cutters” would wreak on content providers and included the results of an assignment he gave his students at NYU to draft up “the next big thing” for the TV industry. What they came up with was “a low-priced pay-TV sampler,” offered by cable companies, “designed to offer just enough TV to get a cord-cutter hooked, but not so much it competes with or cannibalizes mainstay cable packages.” The students named this fantasy streaming platform “Ditto.”

Nearly a decade later, Shapiro’s manifesto has proven prescient: TV isn’t dead, there’s more of it than ever — a direct result of those cord-cutting millennials turning to streaming platforms. (Credit to Shapiro for also predicting that Twitter would be the future venue for water-cooler chat.) This is especially true for comedy. For younger viewers, late-night shows are less a cable-viewing experience than a YouTube or Twitter clip-viewing experience the next morning. Tentpole series like Saturday Night Live and Insecure can be fired up on demand. A pile of Comedy Central stand-up specials and series, including critical darling The Other Two, have shifted off the linear platform to outlets like HBO Max and YouTube. So it’s not far-fetched to think that a Ditto-like platform for comedy would have worked. In fact, three years after he released his manifesto — long before the birth of Peacock — that’s exactly what Shapiro (Shap-eye-ro, not Shap-ee-ro) proposed with Seeso (See-so), NBCUniversal’s first, but not final, subscription-based video-on-demand service.

Following its beta introduction in December 2015, Seeso burned brightly from January 2016 to November 2017. While at its helm, Shapiro played some combination of Willy Wonka and the Music Man, but with great hair. He acquired and remastered classics like Monty Python’s Flying Circus and The Kids in the Hall. He created a space to binge Saturday Night Live, Alan Partridge, and Parks and Recreation. He bought or commissioned programs from the likes of Scott Aukerman, Steve Coogan, Noel Fielding, Kulap Vilaysack, Dan Harmon, Wyatt Cenac, Paul Reiser, Cameron Esposito, River Butcher, and the Upright Citizens Brigade. He gave them and the other two dozen Seeso employees and partners interviewed for this piece so much creative freedom that they would continue to sing his praises years later, even after the platform crashed and burned under his leadership. Blame a flawed rollout, buggy technology, lack of network support, Shapiro’s spending and lack of corporate oversight, or all of the above — the platform maxed out somewhere near a paltry 300,000 subscribers and cost NBCU roughly $60 million across a three-year span.

Today, Seeso is survived by a few hats, hoodies, and chapsticks; as a reference point in pitch meetings; and as the butt of many jokes by those who remember it. During its two-year life, Seeso became an experiment in what not to do in streaming: botch your ad-revenue strategy, fail to promote the platform, fumble the exclusive streaming rights to The Office. But for all its mistakes, Seeso was a gift to comedy nerds — a super-specific kind of streaming platform that provided two-thousand hours of ad-free zaniness, including more than 70 shows and nearly 40 movies and specials, for $3.99 a month. What was it really like to ride this weird, before-its-time train before it went off the rails? Vulture spoke with the architects of Seeso, and the creators they courted, to find out.

“One version of the future was what we were calling ‘baby Netflixes.’”

In December 2014, after launching a now-defunct cable channel from Participant Media called Pivot, Shapiro was on the lookout for a new opportunity. A friend at NBCU’s recruiting office told him they wanted to build something in the streaming space with a comedy bent, and he was hired as the company’s first-ever executive vice-president of NBCUniversal Digital Enterprises. He had already proved himself by running Sundance Channel and IFC, bolstering the latter’s comedic reputation. The yet-to-be-named subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) service was approved in January and announced in March. Concrete budget details are unavailable, but former staffers say there was talk of NBCU planning to invest as much as $100 million.

Justin Purnell (director, content strategy and operations): The idea for Seeso was cooked up by NBC Digital Enterprises, which is sort of the umbrella group for digital efforts. There was a model that a couple of people in the business-development group put together that had a bunch of different ideas for subscription video, and the first test case was meant to be comedy. The idea was that, if you were into comedy, we might do sci-fi next or horror. One of the models had sort of an extreme-sports idea.

Evan Shapiro (EVP, Digital Enterprises): What I was proposing inside NBC is: You are better situated than anyone else to build the next comedy channel in the great streaming bundle. Let’s do that. You’re gonna have to lose a decent amount of money to get there, just like Comedy Central did in the early days. But eventually you’ll have the beachfront property in whatever the NBC/Comcast bundle winds up being. You’ll have the number-one cable channel.

Dan Harmon (co-creator, HarmonQuest): Sony had launched Crackle already, and there had been a couple other things. And it was clear enough that one version of the future was what we were calling “baby Netflixes.”

David Jargowsky (executive producer, Take My Wife and Bajillion Dollar Propertie$): Evan was like, “Basically we’re going to live in a world where Hulu, Amazon, and Netflix become the ABC, NBC, and CBS of a streaming world. And what I want to do is I want to carve out a place where I can be the IFC-type programing platform that will still be able to make it. Now, what I need in order to do that is to create premium programming with interesting people that have audiences that will follow them to a place to watch the programming.”

Shapiro: We did 11,000 half-hour interviews with consumers before we even came up with a plan. We came back with what we thought was a pretty clear diagnostic tool, which is: Put all Saturday Night Live up there, put all next-day Seth Meyers and Jimmy Fallon up there, but go get things, build a deep library, basically to be the retention tool and the stickiness factor.

By summer 2015, Shapiro had assembled a ~30-person team composed of NBCU employees and former colleagues from IFC to work in two offices: a small one in Los Angeles, and the bulk of the team in New York City. Notably, the New York team was housed in a Comcast-owned space in Soho, not NBCU’s offices in 30 Rockefeller Center. The thought was that Seeso would have a start-up, self-sufficient mentality that was better served by being distant from HQ.

Scott Aukerman (executive producer, Bajillion Dollar Propertie$): Comedy fans move around from platform to platform, so I definitely felt like there were a few great years at IFC where they were so interested in doing smart, weird comedy, and then the people who are your champions over there, they all leave the company. That’s kind of what happened with Seeso. There was a big cluster of the people who moved from IFC to Seeso, and the other cluster kind of went to other places, some of which are buying stuff right now.

Purnell: I was at Comcast/NBCUniversal as part of a rotational program for post-MBAs. I started working on NBC News’ approach to younger audiences. When I first heard Evan’s name, they called him “the millennial whisperer.” I saw a couple of presentations he put together, and then someone mentioned that they were in the early stages of putting together what would be known as Seeso. I met with Evan and Ben [McLean, SVP, operations and strategy]. My background being what it was, they asked me to come in as the director of content, strategy, and operations, which was sort of a purposely vague title meant to sort of cover kind of anything. Evan did a very good job of building a culture in a very short time. I think we had a group of people that were dedicated, close-knit, and committed to the cause.

Dan Kerstetter (manager, content and programming): I was running point on IFC’s Garfunkel and Oates and Birthday Boys. Around that time is when IFC started to go through some crazy layoffs, so I was a part of that. I was out of work for about three months before Evan called and told me about this new section at NBC he was going to be heading up called Digital Enterprises.

Annamaria Sofillas (senior coordinator, programming): My responsibilities at Seeso ranged from developing and producing original series, reading scripts and giving notes, helping to decide what to greenlight, taking pitches and submissions and generals, approving cast and writers and directors … We all did a lot.

Kerstetter: Evan brought me in to be his head of programming. And then he brought on Kelsey Balance. He had worked with her at Pivot; she’d be the co-head of programming with me. So I’m heading up the East Coast office, and she was heading up the West Coast. Our yin and yang was she was a little more nuts and bolts, and then I was more like, Here’s the programming philosophy and big picture-y, of putting the comedy-nerd knowledge I had to actual use, finally.

Jonah Ray (Hidden America With Jonah Ray): Dan was always very good. He had a great comedic mind, whereas Annamaria had this amazing ability to understand the heart of these characters in the show, which is a weird thing to say about a sketch show. But she really made sure it felt complete, like it felt of a piece.

Wyatt Cenac (Night Train With Wyatt Cenac): I feel like Evan, Dan, and Annamaria were all fans. They all seem to be fans in a way that sometimes you have executives say they’re fans — some say it to get your defenses down so they can poke and prod and change things — but the three of them genuinely seemed like they were fans where they were like, “No, no, we want you to do what you do, and the main thing we’ll have to keep an eye on is the budget.” Even then, they didn’t keep that great of an eye on it because I went over. Suckers.

“I knew people would make fun of it, but that was going to be part of the joke.”

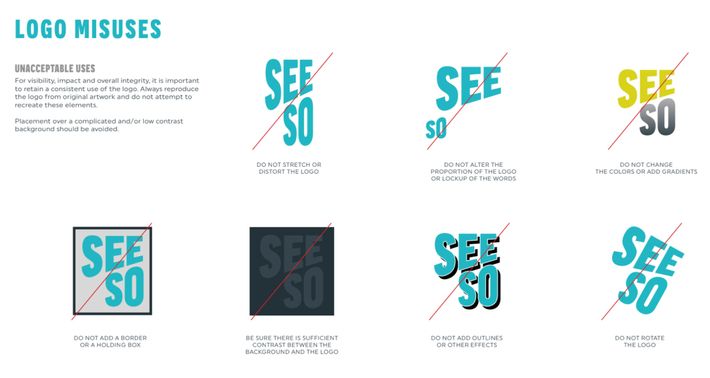

Through spring 2015, staffers engaged in a debate over what to call the eventual product. A boatload of suggestions were partitioned into a sort of tournament, including possible names like “Picky” and “Yaffle.” “Seeso” came late in the process, and many on both the production and business side of the platform were never exactly clear on what it meant. Once the name was settled on, Shapiro contracted a digital ad firm to come up with a simple, eye-catching logo that met two criteria: readable as two words, and, if you are standing on the street, and the logo goes by on a bus, you can still make out what it says.

Shapiro: I actually had chosen a name in early 2015 based on what was happening in North Korea and Sony and The Interview, the Seth Rogen movie. There’s a phrase in the movie called “velocity of the head chunks,” and I came up with a name called “Head Chunks,” and we could own those words. We were basically at the finish line, and then one person inside the corporation decided they didn’t like that name.

Purnell: Evan had a list on his wall. He had a whiteboard on his wall and had everything there we could think of. We had some weird Latin phrases at some point; it was kind of all over the place. And eventually we had what you could call a little NCAA tournament of names.

Kerstetter: It came down to two names: Seeso and Picky. I think they did some internal research to see what URLs that were real words NBCUniversal owned. Picky was one of them, and during the quarterly off-site, we’re all voting between the two. And Evan had this whole idea of, “We can decontextualize Picky. We can make it less of a negative, like, ‘There’s so much in this world to be picky about. Let us handle your shows for you,’” or something like that.

Shapiro: The basic value proposition is we get the best shit on Earth — that was what we kind of came up with — and when you look at what the offering was, I think we actually stood that up. Someone asked me in a meeting, “How do we tell consumers that? How do we convince them?” And I say, “See so for yourself.” I wrote that down, and then went home that night and found that Seeso, as a trademark, didn’t really exist. The URL was owned, but not standing up. I basically convinced everybody that that was a name we could own.

Kerstetter: I think it sounded web-y. And some of the notions were like, “You came to see SNL, so check out The UCB Show. You came to see The Office, so check out Bajillion Dollar Propertie$.” That was the idea behind some of the marketing that never came to fruition.

Cameron Esposito (Take My Wife, Cameron Esposito: Marriage Material): You see this, so you’ll like that.

Shapiro: I knew people would make fun of it, but that was going to be part of the joke.

Tim Baltz (Shrink, Bajillion Dollar Propertie$): The name Seeso, when people drag on that, I’m like, Shut up. You have Netflix, you have Hulu, you have Crackle. The name doesn’t matter if it sticks around; staying power dictates that you’ll normalize it. But the font and the color of the font, I don’t know … that always gave me a bit of an uneasy feeling.

Ryan Gaul (cast member, Bajillion Dollar Propertie$): If it works, people will love the name Seeso. If it doesn’t, people will make fun of it forever. And now they are.

In the lead-up to the December 2015 launch of Seeso’s beta platform, staffers began cultivating a catalogue aimed at the typical comedy nerd. The Seeso thesis banked on viewers being attracted to its library: Universal-owned comedies like Fletch, late-night shows, SNL, Saved by the Bell, and every British comedy show you’ve (n)ever heard of. The plan was to mimic the Netflix model: Get viewers in the door with properties they knew, then get them hooked on original content from there.

Shapiro had worked with Monty Python on a documentary for IFC in 2009 and, years later, was able to convince their reps to let Seeso digitize, remix, and remaster nearly all Python content for online consumption for the first time. That acquisition was part of a larger strategy to attract fans of British comedies not widely available in the U.S. Negotiations continued through the following spring — well after the January 2016 launch — to lock down exclusive streaming rights to The Office and Parks and Recreation. These would be huge draws to the platform, but would result in NBCUniversal foregoing at least tens of millions in revenue from Netflix.

Purnell: NBC had, I think, just done a deal with Lorne Michaels, with Broadway Video, to get full ownership of SNL, so obviously that’s the crown jewel.

Shapiro: The only reason Monty Python’s Flying Circus and a lot of their other content is on Netflix right now is because we took the care to turn it into a product that people can enjoy now in HD for the rest of eternity. Same thing with The Kids in the Hall, by the way.

Kerstetter: Jumping from Python, I went for all things Mighty Boosh. It just felt totally like those things are very similar to each other. So now, what shows have Noel Fielding and Julian Barratt and Rich Fulcher done? Why don’t we acquire these things?

Kulap Vilaysack (creator and executive producer, Bajillion Dollar Propertie$): It was going to be like a record shop, you know? It was something really curated.

Baltz: It’s still the only place that has put Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace on anything in the U.S. So you got to take your fucking hat off for that. I don’t care how cynical of a comedy nerd you are. If you can’t give it up that Seeso was the first to do that, you can go suck bricks, or whatever the saying is.

Brian McCann (executive producer, Debate Wars): They had Black Adder, stuff like that — things that were largely off the radar that didn’t deserve to be off the radar because they were all so cool.

Connor Ratliff (The UCB Show, Debate Wars): They had all of Alan Partridge, including super obscure stuff. They had a lot of British comedy that you can’t get anywhere.

Shapiro: But it was going to require something truly special to be the thing that got people to sign up in the first place, so it’s going to be a combination of price and then unique offer. The center of the plan was to take The Office off of Netflix and Parks and Rec and move them over to Seeso exclusively. It meant forgoing eight figures and a lot of revenue for the company to take these two shows off of that player. Then at the 11th hour, Netflix, who claimed we didn’t necessarily have the right to do that, wrote a big check, and the corporate bosses decided. Netflix offered more money than was already guaranteed to keep it exclusive.

Purnell: We came in thinking of The Office as a tentpole show for the service, but people were already watching it in other places, and no one was going to pay for Seeso to watch something they already had somewhere else. When we let it go, it did free things up a bit for originals, which were much more useful in getting people to subscribe.

Shapiro: My understanding was Netflix paid $100 million just for The Office. By the way, that wasn’t just to keep it. That was also to make it exclusive too, meaning you couldn’t stream it anywhere else. When that happened, I actually turned to Steve and to the CFO at the time and said, “I hope everybody remembers us when we’re losing money.” And in both cases, I was told, “Yeah, no, definitely, it’ll add in.” That’s not what happened.

“We wanted to find things that didn’t feel like they belonged anywhere else in the current TV atmosphere.”

Once The Office and Parks and Rec were off the table, the Seeso team was given more resources for original programming. As they built the platform’s library over the course of 2015, the programming team set out to find the right blend of comedic talent for original shows and specials. They had less than a year to approve and produce work that would, in theory, champion diversity on both sides of the camera. Many creative partners commend Shapiro for his inclusion efforts, but, even if you remove all the British content, Seeso’s programming line-up is pretty pale.

Sometimes Seeso architects bought shows already formed. Sometimes they said, “We want to work with you. What do you have?” Sometimes they bought an idea and it turned into something else entirely. On occasion, creators were given the impression that their shows could make the jump from the platform to one of NBCU’s other properties, maybe even NBC itself, though that never happened. And Shapiro wasn’t afraid to spend what money he had to make the shows work. Seeso’s original content was free from the sort of top-down, network notes that can stifle creativity, but along with that creative freedom came productions that stretched or went over their budgets, which ranged from $100,000 to $500,000 per episode, according to Shapiro and Purnell.

Sofillas: We went to them and asked, “What’s the show you’re dying to make that no one else is offering you?” We couldn’t give them a ton of money, but we could do it for a fair price and give them the creative freedom to make what they wanted, and we would all be partners and collaborators in this new thing together.

River Butcher (Take My Wife): They were working with veterans, but they weren’t limited only to people that were coming in with a quarter-million followers. They were supporting artists and comedians who had small social-media followings, but they saw very early on a lot of unique visions, and that’s what they wanted to carry out.

Jargowsky: Evan did a really good job of looking at the comedy landscape and saying “Okay, well, podcasting is a bit like grassroots meritocracy. So if we look at these factions of people that are getting traction there, we can stitch together this audience quilt of people.”

Esposito: There was just less to risk for each show financially, so they could take much bigger risks creatively.

Shapiro: We came up with a programming filter: bold, authentic, funny. Bold is easy to do. Authentic is easy to do. Funny is not so easy to do. When you try to do all three things together, you get a very unique point of view. I think HarmonQuest, Hidden America, Take My Wife, Shrink, and Flowers all kind of speak to that.

Kerstetter: If a show felt like it could have gone to Adult Swim or Comedy Central or FX, then it wasn’t right for us. We wanted to find things that didn’t feel like they belonged anywhere else in the current TV atmosphere. We didn’t want to try to do a version of what any of the other key comedy players were doing.

Harmon: Evan had that same eye and that same kind of shrewdness of like, “Let’s get into business with the smart people that don’t need a bunch of money. What they actually are craving is respect. I’ll give them that respect, and then I’ll get more bang for my buck from crazier people.”

Seeso’s beta platform launched on December 3, 2015 for about 10,000 viewers, according to Shapiro and Purnell. The beta version featured Seeso’s curated library and a handful of original properties: The UCB Show, The Cyanide & Happiness Show, and Dave & Ethan: Lovemakers, among others. Prior to the beta period, Seeso’s leadership, alongside executives at NBCU, set lofty expectations: 700,000 paid subscribers by the end of 2016. NBC planned to spend $10 million in in-kind advertising across its networks to make this happen. But according to Shapiro, Seeso actually got “one-tenth of one percent” of the advertising they were promised. Less than two months after the official launch on January 7, Seeso’s paid subscriber count was fewer than 20,000.

At that point, in March, Steve Burke (then the CEO of NBCUniversal, now its chairman) told Shapiro that he had to revise and lower Seeso’s projections to about 250,000 subscribers, a goal that the platform did end up meeting by the end of 2016. But the platform (and, some say, Shapiro) never really regained the trust of its parent company, which resulted in a half-hearted effort to market Seeso on NBCU’s other properties. According to Shapiro, about two weeks of ads, a few hits on late night, and one Today show visit for Dave & Ethan: Lovemakers comprised the bulk of NBCU’s intra-promotional efforts.

Some sources claim the parent company was to blame for the product’s inoperability, too, unusable as it was on streaming devices like Apple TV (a mistake that Quibi, perhaps, should have learned from). In 2006, Comcast purchased a media publishing firm called thePlatform, whose content-managing system was brought in to handle things like Seeso’s subscription flow, back-end analytics, and credit-card processing. thePlatform contracted a company called Accedo to build the actual video player on Seeso’s website and mobile apps, which was buggy from the get-go. The streaming service’s future looked bleak until it joined Amazon’s Streaming Partners Program and became available to Prime members in May 2016.

Patrick Cotnoir (digital producer): The launch was really exciting! We had all this original content ready to go. A lot of people felt like, This is something I would use. I want to do a good job.

Shapiro: We were left alone to make our stuff and to build our thing, but we were also left alone when it came to getting behind the project and making sure that it had the reach it needed to launch successfully. Then on top of that, we weren’t left alone in certain circumstances. We had to use the technological products that were built inside Comcast, and that was somewhat limiting.

Purnell: I will forever hate Accedo.

Shapiro: I was incredibly naïve as a product runner. I mean, I didn’t know shit about it. We hired good people, but at the end of the day, standing up an SVOD in a world where Netflix has 5,000 engineers working on it constantly and Hulu has 3,000 engineers working on it constantly, and Amazon has tens of thousands of engineers working on their product constantly … Trying to do that as an out-of-the-box solution from a bunch of different vendors without an internal engineering department dedicated to the product was a bad decision, and it hurt us, especially around launch.

Purnell: I don’t think NBC put expectations on Seeso that Seeso didn’t suggest were achievable. We didn’t help ourselves with the way that we continued to approach them with our numbers.

Shapiro: It was guesswork, and we put very high numbers on it at the beginning. That’s definitely my fault. I tend to really try to point for a hill and then take it. Right around launch, we understood that the product wasn’t ready. Marketing wasn’t necessarily ready either. My bosses told me to “recalculate, recalibrate, come up with new metrics for the end of the year.” We did that, and then we met those metrics.

Dan Ahdoot (Bajillion Dollar Propertie$): Anytime we told someone we’re on the show, we’d have to tell them what Seeso was and what they were trying to do and how to subscribe and all that stuff. So it was kind of like we were actors on the show, but also ambassadors for the new network.

Shapiro: I would also go hat in hand around to the other places and ask Bob Greenblatt [then chairman of NBC Entertainment], Chris McCumber [then-president of Entertainment Networks — USA Network & Syfy], and the other managers of the businesses there for internal promotions. And look, they had their own promos to run, their own businesses to run. So I understand that. But internal promotions were also never mandated. When you look at how Disney promoted Disney+, when you look at how Viacom and CBS promote CBS All Access and Showtime Anytime, when you look at how Peacock is being promoted now, you cannot watch an NBC property right now and not see an ad for Peacock.

Kerstetter: If we could have done things differently, we would have held off on launch. We would have launched with ads, and we would have tweaked our rollout strategy so that we weren’t putting out a whole new series every week or every other week. We probably would have done something like the [now defunct] DC Universe app; they put out like two or three episodes of the new season of something, and then one episode weekly after that.

Shapiro: The deal we made with Amazon was going to become kind of the template deal with people like DirectTV Now and Hulu Live, and YouTube TV and all the other virtual MVPDs. The goal then was to team up with the corporate infrastructure and have them be the partner to sell it out there in the world.

“Make sure that this thing is so fun to make and so satisfying for us as creatives that it would warrant having done it and it never seeing the light of day.”

After a disappointing launch in January 2016, Seeso found some footing over the course of its first year, with the premieres of well-received series like Bajillion Dollar Propertie$, HarmonQuest, Debate Wars, Hidden America With Jonah Ray, and Take My Wife, arguably its biggest critical hit. The marketing was centered on an ad campaign that leaned into Seeso’s niche appeal and hailed its viewers as connoisseurs of artisanal comedy, including a contrived national holiday, The Day of Ha, in which streaming was free for 24 hours on February 21. The platform received outsized attention, especially in the New York Times, and featured a number of well-reviewed stand-up specials. The Grey Lady described Seeso thusly: “There’s a reason that Seeso, the comedy streaming service, is on this list more often than any other outlet: It takes more chances.”

Some technical improvements were made to the player, and Seeso finally became available on streaming devices like Apple TV in December 2016.

Aukerman: The first two seasons of Bajillion and the first season of Take My Wife were like the golden years of Seeso for me, where everything was going great. Everyone was super excited about what was going on.

Baltz: There was a little bit of a honeymoon where we just got to enjoy people watching the shows.

Matt Besser (Besser Breaks the Record, The UCB Show): My pitch for The UCB Show, which would apply to a lot of those shows, is when you’re in the middle of a country, you don’t you don’t get to experience the UCB theater. So a lot of people like to watch comedy stars, but there’s other people who like to see comedy performers who are going to be stars — that excites them. That’s what our show was.

McCann: With Debate Wars, I really think we created a very good show for them, and I think other people were creating very good shows for them. I don’t think there was any issue with their creative approach or commitment to their mandate of what they were supposed to be putting out there.

Jargowsky: It felt just very ascendant. It felt like the audience was going to find it.

Vilaysack: I had never done anything before. I was a first-time female showrunner, woman of color, running this, getting all the experience, working with people I really love to work with. With Bajillion, I got four seasons and a low budget. But it ain’t nothing to sneeze at. I’m so proud of it.

Shapiro: We met with Dan Harmon via teleconference to convince him to bring himself back to NBC after a not-great experience and make HarmonQuest with us. I convinced him to make it half live-action, and together we created something that is indelibly unique and will never be replicated.

Harmon: I was particularly frank with Evan as he was pitching any idea of doing something for Seeso. I said, “I don’t know that the thing that you’re launching isn’t necessarily going to be the next Netflix. I also don’t know if it’ll be gone tomorrow, because I can’t control that aspect of our industry. So that’s why it’s all the more important to make sure that this thing is so fun to make and so satisfying for us as creatives that it would warrant having done it and it never seeing the light of day, because that’s a possibility we have to take on if we indulge in this kind of potentially fly-by-night streaming service.” And he took that well in stride.

Esposito: We were not just nominated for GLAAD Awards — I hosted the GLAAD Awards that year.

Butcher: I think that lasted for 30 days, probably. But that’s how quickly all this stuff works.

Seeso’s second full year started out strong. Subscribership continued to rise and would max out close to 300,000 by spring 2017. Shows like My Brother, My Brother and Me and Shrink debuted to positive reviews in February and March. But dark clouds loomed. The platform had burned through the majority of its $4 million advertising budget by the end of its first year (by another account, Shapiro and his team had blown through the entire 2017 budget by the second quarter), and executives at NBCU began questioning their return on investment.

Then came There’s… Johnny!, Paul Reiser’s passion project that he’d been trying to make for 15 years, and that Shapiro bought (“in the room,” as the parlance goes) in fall 2016. A behind-the-scenes period comedy about Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show days starring Tony Danza, the show was a dramatic departure from Seeso’s other original offerings both in style and price, costing a little more than $1 million an episode.

Shapiro thought of Johnny as a “moonshot” effort to broaden Seeso’s audience and make some prestige television. It was meant to premiere around the 55th anniversary of Carson’s takeover of The Tonight Show, now hosted by Jimmy Fallon. Those involved were banking on heavy cross-promotion on the program that never manifested. The platform would shutter before any episodes were released. A number of Shapiro’s colleagues considered it irresponsible to spend so much on a show, but Shapiro remains unrepentant. All agree it contributed to his firing in late April 2017. In May, NBCU announced Shapiro was stepping down, to be replaced by his superior, Maggie Suniewick, the president of NBCU Digital Enterprises.

Shapiro: My hope and wish at the time was that we would launch There’s… Johnny! with a coordinated effort of The Tonight Show and Jimmy Fallon, and I was flatly rejected and then shown the door. Yes, it was more expensive, which was, I think, the major sticking point between me and the brass there. But it was still substantially less per episode than other major shows on all the other networks.

Paul Reiser (There’s… Johnny!): It’s such an example of how show business works sometimes: like 15 years of me pitching it, then hitting a dead end, and then we’d bring it up to Johnny’s people every once in a while and it would sit for four or five years. The minute Evan and I got together, it just had this wind at its back. It was a great experience. And it saddens me, what it could have become. I mean, I was really eager to do it, and we already had plotted out a second season.

Shapiro: In the budget meeting at the end of 2016, they found out how much I paid. I don’t know why that was a surprise, but they seemed to discover in the meeting how much we had budgeted for There’s… Johnny!, and it was not a good moment.

Sofillas: On Monday morning, a same-day 10 a.m. all-staff meeting popped up in my calendar as I was on my way to the office. My first thought was that it was to congratulate the group about the previous week’s premiere of There’s… Johnny! at the Tribeca Film Festival. It was a video conference, and they just came right out and said that Evan was leaving the company, stunning us all into silence. The meeting ended within five or so minutes — we just had nothing to say in response. It was a big shock.

Shapiro: The major conflict that came between the corporation and Seeso was: You have to prepare to lose a shit ton of money. I used to do the speech that Sean Parker/Justin Timberlake does in The Social Network all the time to the corporate infrastructure. You know: “A million dollars isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? A billion dollars.” You have to scale, and we’re competing against companies that plan to lose money on their way to scalability. We have to be in that game.

Cenac: Both Dan and Annamaria, I think, when Evan left, they said, “Everything’s gonna be moving forward, have no fear.” But it also felt like, Okay, this thing is probably done. And then six weeks later, it was done.

Harmon: How could Evan be leaving but Seeso’s going strong? It was pretty obvious as we got off the phone that what they’re not allowed to say is they’re not believing in Seeso, so Evan’s going, which means Seeso’s going, but at a time that’s more conducive to their quarterly earnings, you know?

Shapiro: I had my fourth boss in two years. They had a lot of decisions to make on where the money and resources were going to be put. It was clear that there was a major disagreement on how I managed the programming budget versus how the corporate accounting department wanted me to manage it.

“They should have looked at it as a poker chip on the craps table that was going to pay off over time.”

Over the course of Seeso’s roughly 20 months of existence, the platform never acquired the critical mass necessary to, in the minds of its parent company, justify further expenditure. Seeso struggled to win over its targeted audience of professed comedy nerds and, even as successful shows were renewed for multiple seasons, their budgets kept creeping upward. The platform was still generating over a million dollars a month in subscription fees when NBCU announced in August 2017 that it would shut the service down in November. In its remaining months, Seeso was basically stripped and sold for parts, with several fully produced, never-aired seasons of television purchased by other outlets.

Reiser: I think we have the distinction of being the first show to ever cancel the network.

Shapiro: I think the new leader [Suniewick] was challenged with the following phrase: You only have so much money to spend in the next two years. Do you really want to spend it on that thing? And I think that person made a calculated decision to say, No, it’s not my thing. I don’t want to have to defend it. I’d rather try to win other battles.

Kerstetter: I feel like our rollout and streaming strategy was flawed. Some money went into certain shows or resources that would probably have been spent better elsewhere. And we probably needed an executive within NBC proper who was fully onboard with our vision to help protect us and adequately course-correct.

Shapiro: We were left to our own devices to make something. Then we were also left to our own devices when it came to promoting it and getting the word out, which was not necessarily the plan.

Esposito: We could call Evan directly. I could text the head of the network. For how small that all felt, when it came time for the show to be sold, when Seeso was being shuttered, that was the first time I realized, Oh, we were only looking at one branch of a global conglomerate. Because NBCUniversal was our parent company, and even NBCUniversal has a parent company.

Purnell: Switching to a subscription model from an ad-supported business was a top mindset change. We might have had a group of pirates down in Soho who were all about that direct-to-consumer relationship, but there are a lot of people at NBC, up at 30 Rock, who didn’t share that mindset.

Kerstetter: The most unfortunate thing was stuff that didn’t get to see the light of day. I know Bajillion eventually sold their catalogue and fourth season to Pluto, so that was able to finally get out there. We had a bunch of stuff in the development pipeline like this pro-wrestling cartoon with Ron Funches, like a handful of other things that were super funny, but just unfortunately gone by the wayside.

Ray: It’s another thing in showbiz where you can make a painting and then they say, “Well, we don’t want to pay for this to be on the wall anymore.” And you go, “Well, can I have it back to put it on another wall?” And they’re like “No, we’re going to put it in a vault.”

Esposito: It was really tough finishing the second season of Take My Wife. Then we didn’t have an answer about whether it would air anywhere for, I think, for eight months. And then I found out that Starz had interest in purchasing it.

Harmon: I think Seeso at its inception was a perfect risk-liability balance for NBCU. It was cheap to launch, and it covered up that they might have been nervous about the future. So the mistake I think they made — and I do think it was a mistake — is that that thing, if it’s going to succeed, is not going to succeed overnight. They should have looked at it as a poker chip on the craps table that was going to pay off over time.

About half of Seeso’s library was sold to other platforms. There’s… Johnny! premiered on Hulu in November 2017, and is now on Peacock. Bajillion Dollar Propertie$ went to Pluto TV, and Night Train and Take My Wife went to Starz (but are no longer available on the network). HarmonQuest, Hidden America, and My Brother, My Brother and Me went to VRV. The comedy specials were acquired by Comedy Dynamics, an independent distribution company. Shapiro decided to stop trying to run networks and focus on content itself. In 2019, he was tapped to resuscitate the National Lampoon comedy brand, which he ran until September 2020.

Those who toiled to produce as much content as they could during its brief lifespan remain bittersweet: They’re happy to have had the experience, but sad that more people didn’t get to see its uniquely joyful content that came with a network quality but without a network’s notes.

Shapiro: How does something that lasted two years have a legacy? I don’t know. I mean, the shows, I think, obviously are that legacy. But a lot of the strategy we used is now being baked into Peacock. So whatever happens there, for good or bad, will be part of that.

Baltz: I got heckled at a stand-up sketch show by a dude for being in a Seeso show. I wasn’t even onstage. I was in the audience.

Travis McElroy (My Brother, My Brother and Me): We still get people asking about us doing a second season of it, and the further we get away from it, the stranger it seems.

Vilaysack: The people who have shows up on Peacock right now, which they are putting full resources in, are your Tina Feys — these people who are proven. They’re geniuses, but they’re proven producers, showrunners, writers, which will warrant higher budgets. There’s more at stake, right? So there is going to be more oversight. And I can’t get a show on Peacock, you get me? Had NBC put all of their resources into Seeso, I wouldn’t have gotten that show, is how I feel.

Ahdoot: It’s one thing if you’re a part of a project that gets out there and then the public says, “No, we don’t like it.” It’s another thing if you make an amazing project and people don’t know how to fucking find it.

Kerstetter: There aren’t many specific SVOD services like that that are that cheap right now. Everything is kind of rolled up into large verticals, like Disney Plus put all of their umbrella verticals underneath that. It seems like most people have taken the idea of going big, like HBO Max.

Baltz: The pathway from basically doing improv to doing something else — those pathways don’t really exist. They’re a pipe dream of the 2010s: that you can be good in an improv show and then just get shit handed to you.

Harmon: Every single brand you serve potentially has a small erosive effect on your own brand. Because who is Dan Harmon, if Dan Harmon is going to keep on wandering from portal to portal, hitting me up for money for some snake-oil company? That’s a very cynical way of characterizing all of that stuff. I know these companies are run by decent people who believe in good content and all that stuff, but the bottom line is the artist moving forward in this thing we still call television. They’ve got more opportunities, but it’s going to be harder and harder for Vince Gilligans to get created.

Shapiro: In 2013, nine companies controlled 90 percent of all TV and film content in the U.S. Today, it’s five. That was key to my decision to no longer work on the platform side of the business, because it was going to be hard to be special or unique as a content creator and work inside one of those major companies.

Ratliff: Even though we have so many channels now, it doesn’t necessarily mean we have a lot of places that are really open to doing something that’s a little off-kilter, a little bit off the beaten path, and Seeso genuinely was that.