A story as sprawling and ambitious as the one Severance told in its first season does not materialize without meticulousness. As creator Dan Erickson and executive producers Nicholas Weinstock, Jackie Cohn, and Ben Stiller worked from 2016 to 2020 on adapting and evolving Erickson’s first draft, Severance took on additional layers of mystery and intrigue. Once the series began filming in January 2021, Erickson and Stiller maintained its enigmatic atmosphere by eking out morsels of information to the cast and crew, leading to a cliffhanger season finale that answers some questions about what is going on at Lumon Industries but mostly leaves open the fates of the severed employees within the Macrodata Refinement (MDR) division.

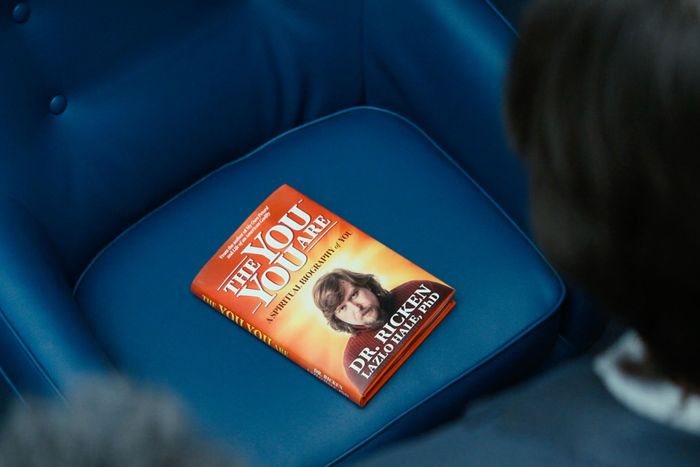

Here are nine short stories about what it was like to make the challenging yet supremely satisfying Severance, from people both onscreen and behind the scenes — anecdotes about finding your character when their motivations are purposefully hidden, crafting the series’ surveillance-heavy visual language, using production design to elucidate the fanaticism of Kier Eagan’s followers, and how Michael Chernus’s Ricken inspired The You You Are, a slightly silly self-help book that becomes the MDR team’s sacred text.

.

First Drafts

My dad was an attorney. He worked for the city of Olympia, Washington. It was this wonderful place full of really warm people, but also long hallways and copy machines that looked to me like something out of a supernatural alien world. The first version of this that I showed to anyone was much more bombastic and had a Terry Gilliam Brazil vibe. At one point there was a pair of disembodied legs that ran by, and Mark was like, “What the fuck is that?” And they’re like, “Nothing, the wind.” So it was a little bit sillier, or at least more heightened in that stylistic way. I think it was through talking to Ben [Stiller] that I really got this sense of, Okay, it might be a more interesting story the more we ground it in its humanity and the psychology of the people who decided to do this.” — Dan Erickson, creator

.

The Look of Lumon

I had worked with Ben [Stiller] before; I did Escape at Dannemora with him, so we kind of tested our relationship to the max on that one. We went through a lot of challenges, but it was a great collaboration, and we stayed in touch after. He had been talking to me about Severance toward the end of Escape, but I was never very into it because it was an office. White walls and hallways, no windows. I love creating worlds and to do something that I haven’t done before. But I felt very limited — it was ten episodes at the beginning, and I’m like, I’m going to shoot an office and it’s going to be the same thing day in, day out. I don’t want to do that. You’re shooting these actors, and there’s overhead lighting and it’s drab. There’s no contrast, there’s no shape to it. I also know Ben, as a director, loves shape in lighting. I felt like I was going to be very limited. I went to a book fair and found a book called Office by Lars Tunbjork, and that was like, Oh, okay. I get it. This is Swiss architecture, ’80s, ’90s office space. It opened a visual world I hadn’t thought of. — Jessica Lee Gagné, cinematographer

.

The Art of Surveillance

Inside the office is a super wide-angle security-camera-driven aesthetic. We wanted them to feel like they were being watched. We use remote camera heads a lot, so movements don’t feel human. In the outside world, everything is more human-operated. There’s definitely a surveillance vibe on the outside; it’s just much more old-school, like a ’70s spy thriller. When you’re using a wide lens inside the office versus a long lens outside the office and you do a close-up, you’re changing your human perspective with regards to this person. When you’re wide, the camera’s closer. So that’s going to emphasize that energy, that proximity, that paranoia, because you’re physically with them. The longer the lens is, the more of a voyeur you are. The more distance you have, the less physically, emotionally implicated you are with a system, with a situation. — Jessica Lee Gagné, cinematographer

.

The Diamond Desk

MDR is the best set. It was so photogenic. You could drop the camera anywhere and you’d have a shot. The green on the carpet helped create contrast, which would create shape — the awkwardness of it, the shapes. And Cat Miler is the most amazing props person I’ve ever worked with. Even the desk — that’s a $100,000 desk. That’s how much it cost to build it. It stands on one foot, just one support in the middle. And all those dividers are on pulleys. Our producer is calling it the diamond desk. — Jessica Lee Gagné, cinematographer

.

Snapshots

It’s an antique camera, it takes real film and real pictures, and I had to learn how to operate it. I had camera coaching where I sat with our props coordinators and they told me how to hold it, the angles in which to hold it, what the shutter does, how you have to flip it and which button to press, everything. Ben made sure it was very authentic, because if it wasn’t right and I held it at a different angle, or if I didn’t flick the lever to make it switch to catch the flash, then we had to do the shot again. — Tramell Tillman, Milchick

.

Selvig’s Space

She has three characters. She’s Cobel at work, she’s Mrs. Selvig at home, and then when she’s in her pigtails and her white gown she’s sort of between characters. So upstairs, if a neighbor could peek through the windows, you could see Selvig, so it was New Age-y and turquoise, very ’70s earth mother. Then in her basement we ended up putting her single bed and a praying area. It was like an orphanage. Her shrine to Kier went through a lot of changes. At one point, we had a lot of things piled up — her crazy side, years and years of things in disarray. But then we did the opposite, made it very sparse and with a workspace, where she makes whatever she needs for her characters. — Andrew Baseman, set decorator

.

The Warm-up

Ben doesn’t like yellow. The guy loves cold things. I love warmth. But he was like, “Devon and Rickon’s house can be warm,” so I said, “I’m going for it.” We went tungsten, where I would never otherwise do tungsten. Ben hates tungsten, so I try to sneak it in. It’s a constant battle between us. — Jessica Lee Gagné, cinematographer

.

The You You Are

If I could, I would write the in-universe books and materials all the time. I really like writing the show, too, but I think that’s my favorite thing to do. Ricken’s book is much more stream-of-consciousness than anything else, because I don’t see Ricken as a big rewriter or even a big checker of the things he does. With Ricken, it just sort of pours out. It’s me purging all the dumbness I have, but then it keeps coming back somehow. It’s so fun and so ridiculous. And especially once Michael [Chernus] was cast in the role, it became so much easier because I would just sit at my desk and do a little Michael impression and try to get in that headspace, and then it all just comes. — Dan Erickson, creator

.

Milchick’s Method

He’s impeccable. Very crisp. Very clean, which speaks to his meticulousness. I was very finicky about tying my tie. I wanted to make sure Milchick had the neatest knot. If it was possible to get a dimple in his tie, I wanted the dimple. My dressers were always very helpful and asked me, “Do you want me to tie your tie?” and I was like, “No, I want to do everything myself.”

Everything was a process: How he put on his socks, how he put on his shoes. Even the placement of his pants is specific. It’s a lot higher, higher than I wear my pants. And all of that informs how he moves. You move differently when your pants are on your bellybutton versus your lower part of your hip. You also speak differently, from your diaphragm.

I was very selective about his hair, wanting to craft it in a certain shape, in a cleanliness, so that it speaks to his personage. I believe Milchick has an entire process, making sure that his hair is very pristine and set for how he wants it for that day. His mustache — let me tell you. This mustache, it would take us an hour and a half to get his mustache right. That was me! Anna Stachow — who does hair and makeup for the show — we sat down and said, “How can we get this mustache to be this extremely specific geometric shape?” There were times when we were nitpicking: “Okay, get this piece. Okay, wait, this piece. Okay, well, what about this?” It seems so obsessive, but it speaks to Milchick’s character. The mustache is a character on its own. It should have its own credits: The Mustache.

I did a lot of stretching, because that also helped me tap into his breath and his movement. There were times on set where the poor crew had to either put cardboard on the floor or put tape under my feet because I would walk so hard. Milchick is a man on a mission. He presses firmly on the pavement. I had yoga poses or stretches where I would remind myself to keep my feet planted, my body straight and strong and upward, broad shoulders, chest out to the world, ready for whatever comes — which also is a form of intimidation. And exercise was a great tool. It helps to keep the engine moving, the blood flowing. I was doing a lot of pushups, I was doing a lot of situps, a lot of squats to keep the engine flowing, and to then find a way after those exercises to tamp down the energy and place everything back into the head. — Tramell Tillman, Milchick