Even the most familiar comforts can grow to feel strange, unreliable, potentially harmful ÔÇö a phenomenon Freud called unheimlich, or ÔÇ£unhomely.ÔÇØ No writer epitomizes the concept of the unhomely more than Shirley Jackson, whose darker fiction ÔÇö ÔÇ£The LotteryÔÇØ being arguably the best-known example ÔÇö eclipsed the broader range of her oeuvre. But she also wrote humorous memoirs that first appeared in womenÔÇÖs magazines, later collected as Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. Critics were confused by the Jackson they encountered in these domestic sketches, unable to reconcile this mother and homemaker ÔÇö this baker of brownies, folder of laundry, and sewer of buttons ÔÇö with the author whose gothic horror was so frightening that her publisher was, as Jackson describes in a 1948 letter to her parents, ÔÇ£playing up lottery as the most terrifying piece of literature ever printed.ÔÇØ Jackson performed a kind of homemaking in her fiction, too: She conjured up houses with the kind of hauntedness that only a housewife, intimately acquainted with the complications of domestic comforts, could. Indeed, she recognized that there is no place quite like the home, a place where the familiar hosts the frightful; where menace coexists comfortably with the mundane.

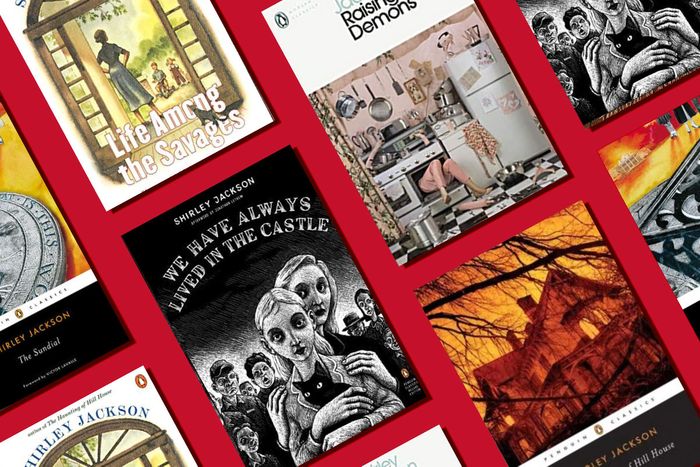

We feel such menace in the homes at the hearts of JacksonÔÇÖs later three novels: the Halloran estate in The Sundial, the titular property in The Haunting of Hill House, and the Blackwood mansion in We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Each home promises lavish comfort, at least for some of its inhabitants; each is built as an extensive world unto itself, a testament to the wealth of its owner; each stands distinct from the wider world, just as a gated suburb self-insulates from its surroundings. But if wealth allows these characters their elaborate exercises in world building, then it also condemns them to suffer the resentment of the surrounding villagers who, like JacksonÔÇÖs own neighbors, tend toward a threatening tribalism.

Jackson also directs our attention to the ways in which material displays of wealth, not just social surroundings, can be alienating. The group that Dr. Montague assembles to investigate paranormal activity at Hill House becomes quickly overwhelmed by its opulence: between the ÔÇ£towers and turrets and buttresses and wooden lace, Gothic spires and gargoyles,ÔÇØ they struggle to feel settled in this ÔÇ£masterpiece of architectural misdirection.ÔÇØ In The Sundial, Aunt Fanny becomes similarly bewildered by the Halloran estate where she was raised, suggesting that the wealthy, by delegating their domestic labor to others, may never feel at home in a place from which they are fundamentally estranged. From its construction to its daily upkeep, the Halloran estate is entirely the work of others hired from the distant city, specifically to keep the villagers out.

It was in these lavish and uneasy homes that Jackson searched for the source of her ambivalence toward homemaking. She had found that domestic life could be complicated both by material possessions and the lack of them. In Savages and Demons, Jackson laments having to move between rental properties but dreams of the mobility that might be possible if her family werenÔÇÖt weighed down by their many belongings. ÔÇ£I look around sometimes at the paraphernalia of our living,ÔÇØ she writes in Savages, contemplating the various sandwich bags, typewriters, and ÔÇ£little wheels off thingsÔÇØ around her, ÔÇ£and marvel at the complexities of civilization with which we surround ourselves.ÔÇØ

Beneath the humor of JacksonÔÇÖs narration pulses a fundamental agitation, in large part owing to a series of sudden, involuntary moves, first from New York to Vermont after being evicted, then from one house to another when the original owner returns to reclaim her ancestral estate ÔÇö┬áÔÇ£I thought someone had told you,ÔÇØ she says, ÔÇ£we are coming home again.ÔÇØ Even after the last moving box was unpacked, JacksonÔÇÖs agitation persisted: no doubt the result of unwelcoming, insular neighbors, her husbandÔÇÖs infidelities, and the stress of managing a growing household alongside a career.

Jackson herself had a difficult relationship with her parents, which played some role in her motivation to foster a happy home. But even as she embraced motherhood and took particular pleasure in cooking, she continued to reckon, through her writing, with the ways that domestic life could perpetuate asymmetries of possession ÔÇö whether of property, the self, or others. Even if they werenÔÇÖt rendered overtly gothic in the way of her novels, these circumstances were no less terrifying to Jackson as they came to dictate the shape of her life: In a description of the entrapment she felt at home in Vermont ÔÇö ÔÇ£as though we had fallen into a well and decided that since there was no way out we might as well stay thereÔÇØ ÔÇö she gives hint of the gritty reality swept under the freshly vacuumed carpet.┬áPerhaps this is why Jackson wrote in Savages that their life could feel ÔÇ£occasionally bewildering,ÔÇØ as if she suffered from the same disorientation that plagues Aunt Fanny within her own home.

If in traditional horror novels supernatural entities haunt homes, then Jackson suggests our fears be redirected toward worldly, proprietary threats that might loom in our own backyards, waiting to break in and seize the house. These arenÔÇÖt demons per se, only individuals possessed by the spirit of property acquisition: like Orianna Halloran, who murders her son to maintain control of their estate; or Mrs. Sanderson, who seizes Hill House following a fatal property dispute; or Cousin Charles, who preys upon Constance, the surviving Blackwood heir, in an attempt to become the head of the house. This is of course the very spirit that animates that white-picket-fenced American Dream, though Jackson is preoccupied specifically with the nightmarish scenarios in which this fantasy becomes subverted: When the property itself, animated by a malignant kind of agency, possesses those who supposedly own it.

Variously characterized as ÔÇ£angry,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£deranged,ÔÇØ and ÔÇ£a place of contained ill-will,ÔÇØ these homes seem to turn upon their inhabitants. To the Blackwood family, all but two of whom are murdered at their dining table, sugar is not saccharine, but poison; the sugar bowl is not merely a prized heirloom, but an accessory to murder. Knowing this, Uncle Julian remarks that ÔÇ£the most unlikely perilsÔÇØ can be found in the home, between ÔÇ£garden plants more deadly than snakes, and simple herbs that slash like knives through the lining of your belly.ÔÇØ There is danger, too, in the conventional ideals that promise domestic bliss. Though Merricat never discloses her motive for murder, she reflects while regarding her late fatherÔÇÖs signet ring that ÔÇ£the thought of a ring around my finger always made me feel tied tight, because rings had no openings to get out of.ÔÇØ Perhaps Merricat, like Jackson herself, desired the security of a traditional family while resisting the confines of its patriarchal arrangement; this would explain her disdain for Cousin Charles, who bears in his domestic incompetence a notable resemblance to JacksonÔÇÖs husband, particularly when he demands to the air, ÔÇ£WhatÔÇÖs for dinner?ÔÇØ

Likewise, the soft, padded sofas at Hill House appear ÔÇ£motherlyÔÇØ at first glance but ÔÇ£turn out to be hard and unwelcome when you sit down, and reject you at once.ÔÇØ The language here is pointed: JacksonÔÇÖs mother, characteristically critical, might also have inspired a description of the nursery in Hill House,┬áwhich ÔÇ£had an indefinable air of neglect found nowhere else.ÔÇØ Their relationship only worsened over time. In response to a glowing review of the bestelling Castle, JacksonÔÇÖs mother fixated on the portrait that accompanied it. ÔÇ£I have been so sad all morning about what you have allowed yourself to look like,ÔÇØ she wrote to her daughter. Jackson withdrew into her home that fall and did not emerge until the following year.

I wonder if Jackson envied that woman who materialized at her doorstep in Vermont, particularly for the ease with which she declared she was coming home again; even when Jackson had a house to return to, the prospect of living and feeling at home there was never straightforward. JacksonÔÇÖs characters are driven out of the homes they want to stay in or are forced to remain in homes they desperately want to leave ÔÇö they are not otherworldly, but in their unsettled lingering they are condemned to become ghosts of a kind. In her struggles with agoraphobia, Jackson might have identified most with Eleanor, who drives her car into a tree when she is banished from Hill House, in an attempt to remain there forever. She recognizes that staying will cost nothing less than her life, but the prospect of leaving is more unbearable. Even the trees and wildflowers that bloom around the property pity ÔÇ£a creation so unfortunate,ÔÇØ writes Jackson, ÔÇ£as not to be rooted in the ground, forced to go from one place to another, heart-breakingly mobile.ÔÇØ

This is the kind of heartbreak that haunts the reader of Jackson, and one that feels particularly suited to a moment oversaturated by inflated rents, stay-at-home influencers, overpriced homewares, and Architectural Digest fodder, in which rates of homeownership are dropping in response to soaring mortgage rates ÔÇö in other words, a moment when domestic ideals are ever-present realities for some yet receding fantasies for most others. It is the kind with which Jackson was thoroughly familiar and which she spent her life writing across various genres, recognizing that the truth of any heartbreak canÔÇÖt be captured by humor or horror alone.