When most people think of Bono, the swaggering, outspoken front man of U2, what they picture is likely not the time he was healed by an ultraconservative senator from North Carolina.

It was in the early aughts when Bono visited the office of Senator Jesse Helms ÔÇö a figure who was┬áopenly homophobic, antiÔÇôNational Endowment for the Arts, and against making Martin Luther King Jr.ÔÇÖs birthday a national holiday ÔÇö and used Scripture to persuade the Republican to support debt relief for some of the poorest nations in the world as well as funding to combat the AIDS crisis in Africa.

ÔÇ£Son, I want to bless you,ÔÇØ Helms said to Bono, as the singer recalls in his new memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story.┬áÔÇ£Let me put my hands on you.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs a scene that, as Bono notes, is ÔÇ£not exactly rock ÔÇÖnÔÇÖ rollÔÇØ and a meeting that his friend and bandmate the Edge was ÔÇ£particularly upset to hear aboutÔÇØ after the fact. ÔÇ£Rock stars in this kind of enterprise are an invitation to lampoonery,ÔÇØ he writes, referring to his second gig as a political activist. ÔÇ£Could I take it? I could take it ÔǪ I wasnÔÇÖt sure the band could. Or if I should be asking them to.ÔÇØ

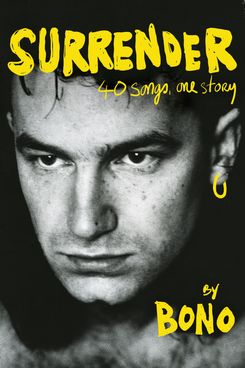

ItÔÇÖs the kind of blunt self-reflection that defines Surrender, a 500-plus page autobiography that occasionally gets bogged down in the micro details of political negotiations but is mostly an earthy, self-deprecating, often funny appraisal of the sometimes contradictory paths Bono has traveled. Those include his roles as an activist who doesnÔÇÖt always know when to keep his mouth closed; a loving but not always physically present father; a steady husband to his wife, Ali, who has been his romantic partner since literally the week he joined U2; and, of course, as the voice of one of the most enduring bands in rock history.

The book is Bono at his Bono-iest: verbose, wry, inspiring, and fully aware of how grating he can be when his ego gets the best of him. His analogies do sometimes smack of corniness. ÔÇ£We had a lot of baggage and it wasnÔÇÖt in our suitcases,ÔÇØ he recalls of the early days of his now 40-year marriage to Ali. ÔÇ£We spent a lot of every day unpacking each other.ÔÇØ But before youÔÇÖve had a chance to groan, Bono makes fun of his own belabored prose: ÔÇ£ÔÇÿWhat did you bring this for?ÔÇÖ Ali asks, as I stretch this metaphor as far as it will go.ÔÇØ

As a longtime U2 fan, IÔÇÖve never fully understood the perception of Bono as someone who takes himself too seriously. His willingness to laugh at himself has always been evident, and itÔÇÖs on full display in Surrender, which, a few goofy metaphors aside, is a lovely, thoughtfully written book. Framed in 40 chapters named after U2 songs, from well-known hits (ÔÇ£With or Without You,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£Mysterious WaysÔÇØ) to deeper cuts (ÔÇ£Wake Up Dead Man,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£LandladyÔÇØ), the memoirÔÇÖs arc stretches from his childhood in Dublin ÔÇö when he suddenly lost his mother, Iris, who died of an embolism during her own fatherÔÇÖs funeral ÔÇö to the present day. Within that structure, Bono writes in anecdotal bursts that arenÔÇÖt in exact chronological order, peppering his observations with doodles and sidebars. (At one point, he includes a list of reasons to love Johnny Cash. Reason No. 6? ÔÇ£Jesus Christ took his initials.ÔÇØ)

Throughout, Bono confesses repeatedly to the many doubts he has harbored about himself and his choices over his years in the spotlight ÔÇö including the famously controversial decision to drop the U2 album Songs of Innocence for free into the music libraries of every iTunes user in 119 countries. He takes full responsibility for that misstep, noting that he initially thought of it as akin to leaving a complimentary bottle of milk ÔÇ£on the doorstep of every house in the neighborhoodÔÇØ:

On September 9, 2014, we didnÔÇÖt just put our bottle of milk at the door but in every fridge in every house in town. In some cases we poured it onto the good peopleÔÇÖs cornflakes. And some people like to pour their own milk. And others are lactose intolerant.

That aggressively generous rollout of Songs of Innocence was emblematic of what some felt U2 had become: a bunch of arrogant old fogies who thought a little too much of themselves with Bono acting as the most obvious symbol of that high self-regard. Anyone who harbors those notions may be surprised by the humility that runs throughout this book as Bono questions, with convincing sincerity, himself and his own behavior.

ÔÇ£It can be bruising,ÔÇØ he writes of the lasting but not always smooth relationships among the members of U2, which formed when Bono, the Edge, Adam Clayton, and Larry Mullen Jr. were in high school. ÔÇ£And I recognize my own role in all this. How I can be over-the-top in standing up for what I believe in, how very wearying that must be.ÔÇØ

As mindful as he is about how he comes across, there are times when that self-awareness slips. While noting that he did not agree with George W. BushÔÇÖs decision to invade Iraq, he adds that it was ÔÇ£a war I sensed he would have fought himself if he had to,ÔÇØ a rich thing to say about someone whose actual military service was called into question. For as nitty-gritty as Bono gets about his interactions with members of Congress and world leaders, he scarcely discusses how his once-bipartisan approach to activism has changed during the Trump era. He does, however, lay out his concerns about the rise in populism and the urgency required to beat back that tide. ÔÇ£The arc of the moral universe does not bend toward justice,ÔÇØ he writes. ÔÇ£It has to be bent, and this requires sheer force of will. It demands our sharpest focus and most concentrated effort.ÔÇØ

In the latter portions of Surrender, Bono wonders how much longer U2 as a band can last, though he doesnÔÇÖt seem to have given up on the joy that can be summoned when he sings of streets with no name. ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs the line I want to walk,ÔÇØ he says, citing Cash as inspiration. ÔÇ£The wanderlust in the wanderer. The spirit that still hasnÔÇÖt found what itÔÇÖs looking for, a life and a gospel song about doubt as much as certainty, about the journey, more than the destination.ÔÇØ