Meghan O’Rourke is a poet, memoirist, former poetry editor for The Paris Review, and the incoming editor of the Yale Review. Below, she rounds up her favorite poetry of the year.

American poetry is having a renaissance — or something like it: Whatever you call the moment we’re in, poetry feels newly invigorated by a potent diversity of voices, rendered with extreme stylistic range on the page. The following, in order of their release, are some of the books I was thankful to have as company — some of the books I needed to read — in 2018. There are others, of course, but each of these remarkable books offers a respite as this long, strange year comes to a close. Each invites us to slow down, to linger on thoughts that unfurl against an expressive white space, and each is a quiet protest against easy truths and alternative facts. These are poets, in other words, who have made silence speak. They have written beautiful books, yes; but also powerful books — of resistance, of voices finally unleashed, of loss, of possibility.

Edited by Farnoosh Fathi, this volume shines a much-needed spotlight on a mid-century poet who died at the age of 24, in 1942. Murray, who had a heart defect caused by rheumatic fever, battled illness her whole life. Her proximity to mortality gave her a mainline to art: “What truth, what mystical awareness can be lived,” she once wrote to her mother. W.H. Auden awarded her the Yale Series of Younger Poets prize posthumously in 1947. Her poems are mystical, surreal, funny, and poignant in their playful visions of a future the poet wasn’t to have: “The grass will not be so insignificant, the stone so dead,” she wrote in one poem. “Drop your lids, little architect. Admit the bats of wisdom into your head.”

Smith is the poet laureate of the United States. Her fourth book, following on the Pulitzer Prize–winning Life on Mars, braids the political and the domestic. The poems here include incisive lyrics about aging, motherhood, and American politics, as well as a section adapted from letters and statements of African-American soldiers in the Civil War and their families. Throughout, Smith’s lines possess a composed gravity that makes their eruption into slyness, anger, or pain all the more powerful. In “Dusk” she writes of becoming a mother, and “all that had grown slack and loose in me,” then unsentimentally evokes her daughter’s “naïve” shoulders, innocently able to “stand squared, erect,/ Impervious facing the window open/ Onto the darkening dusk.”

This strange and luminous volume is one of the great long poems of the 20th century; I’ve been waiting for it to be rediscovered by a new generation of readers. Published here as a stand-alone volume for the first time, annotated and helpfully introduced by Merrill’s literary executor, Stephen Yenser, the poem chronicles the encounters of Merrill and his partner David Jackson with a “guiding spirit” named Ephraim, aided by a Ouija board. A work of remarkable range, The Book of Ephraim is a profound piece of occult narrative and chance compositional practices, overlaid with the virtuosity and penetrating wit Merrill was known for. The result is like no other poem in the English language.

A discerning eye is at work in this debut collection; Xie has a voice at once ironic and poised, restless and deeply meditative. These are poems of meticulous wildness, like the insights that come during a dark night of the soul and are reexamined in the light of day. Traveling from Hanoi to Phnom Penh to New York, the speaker takes us on a journey through what can and can’t be intuited, complicating the very nature of perception: “All that is untouchable as far as the eye can reach.” Stealthily beautiful, Eye Level is one of those immersive books that changes you as you read it.

The propulsive poems in this debut collection, which won a National Book Award, explore all that is indecent and all that is thought (by some) to be indecent, from the prison-industrial complex to black male sexuality. Reed has an amazing ear and his poems are rich with musical echoes and sonic ironies: “The matter of business: / a rug, underneath which sis swept / the living dirt. Go,” he writes in “About a White City.” These crackling poems move insistently toward endings that open onto both violence and joy.

These poems were written, as the jacket tells us, “in the first 100 days of the Trump presidency,” and they have the urgency of protest as well as the formal ingenuity that is a hallmark of all of Hayes’s verse. Each sonnet blasts a new pocket of space into the bedrock of American consciousness: “I carry a flag bearing a different / Nation on each side. I carry money bearing / The face of my assassins,” one asserts. America, another says, just wanted “a return / To the kind of awe experienced after beholding a reign / Of gold. A leader whose metallic narcissism is a reflection / Of your own.” Such poems give the lie to the notion that political poetry must be didactic or inert; they glow like coals, but they burn in the mouth.

A book unlike any other this year, feeld discovers novelty in the English language by looking backward, all the way to Chaucerian English. (Charles, a transgender woman, is a scholar of medieval literature.) The poems explore what charles calls “tran” life and require the contemporary reader to engage in a perverse act of translation — from English to English. The result is a kind of poetic syllogism that formally enacts the absence of the transgender literary tradition (“a tran is a thynge u leeve,” charles writes) while writing its way into that long silence, instilling a sense that the trans poet is asking literature to recognize itself: “i care so/ much abot the whord I can’t/ reed / it marks mye bak/ wen i pass / with/ a riben in mye hare.” Innovative, dazzling, moving, this book is a knockout.

“You who were given a life, what did you make of it?” Gander asks in this book of searching elegies for his partner, the poet C.D. Wright, who died in 2016. The poems interrogate what it means to speak of something as engulfing as loss; they also meditate, rivetingly, on what it means to “be” “with” anyone, whether that is our fellow citizens, our partners, or our own sometimes treacherous minds. The poems are devastating and yet never sentimental, spoken in a severed syntax — the only kind that allows us to speak honestly of being at all.

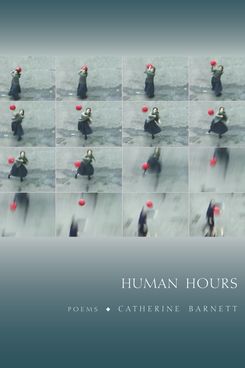

Barnett’s marvelous third collection is populated by devastatingly wry (and wryly devastating) poems about aging, time, and the existential predicaments — violence, trauma, consciousness itself. What makes it so brilliant is the highly ironized point of view of the speaker, who talks about life like someone just entering or about to leave it. This book reminds me more of Emily Dickinson’s work than any contemporary book does. “A doctor suggested I spend four minutes a day asking questions about whatever matters most to me,” Barnett writes in “Accursed Questions, i” — one of a series of lyric essays that pursue interrogation as a compositional mode. Iconoclastic and penetrating, the speaker of these poems unsettles and enlivens.