If you’re looking to sell The Brutalist’s three-and-a-half hour runtime to a friend who hasn’t yet seen the movie, tell them it ends with a really good disco song. La Bionda’s irresistible 1978 track “One for You, One for Me” is a credit-sequence needle drop rivaled only in dissonance by The The’s “Lonely Planet” closing out Megalopolis. Originally conceived for the light-up dance floors of Europe, the track provides an unserious coda to the fictional story of Adrien Brody’s László Tóth, a Holocaust survivor who emigrates to the United States and spends painful years attempting to reunite with the family he left behind in Hungary.

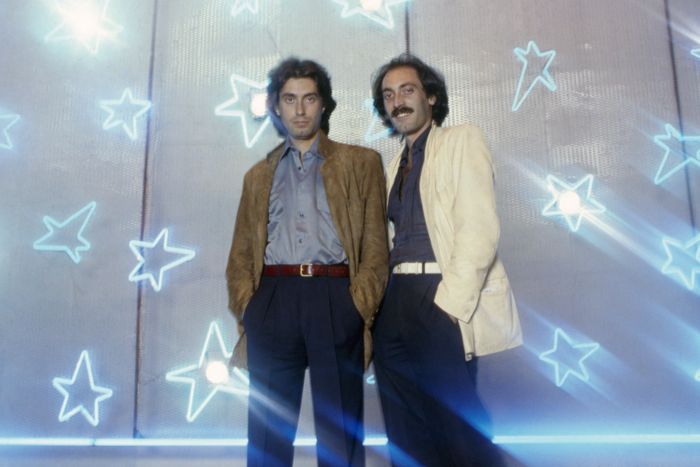

“One for You, One for Me” was dreamed up by Sicilian brothers Michelangelo and Carmelo La Bionda in a German recording studio when they were taking time off from scoring spaghetti westerns. It went on to reach No. 1 in Austria and has since become an Italo-disco playlist staple around the world. Its tone-shifting cameo in The Brutalist has surprised and delighted Michelangelo, who tells us that he’ll be cheering on the movie’s Oscar chances from Milan on Sunday (even though he hasn’t actually seen the film yet). “We were just writing music,” he recalls of La Bionda’s studio heyday. “We never meant to be too deep.”

It was a fun surprise to hear “One for You, One for Me” in The Brutalist. How did the song end up in the movie?

It sounds funny, but somehow it just happened, you know? My son is a lawyer and takes care of the licensing, and the request to include the song came in from the movie’s music supervisor. I think his name is James Taylor. Of course, the musician James Taylor is one of my idols. I understood this was a different person. But I would have preferred James Taylor, the musician.

Have you seen the final cut yet?

Not yet. Because the film only came out in Italy last week and I believe to enjoy it properly you have to see it in VistaVision in a cinema that has the proper system to watch the movie. I’m going to watch it for sure, because a lot of people who’ve seen it have written me to say it’s incredible when the song comes on at the end. I hear people are jumping and dancing at the end of the movie. So I’m very curious to watch it and get that same feeling.

Do you have any theories as to why the song was used in the film?

A song in the end credits, that must have a meaning. And I’m trying to imagine what it is. I’m curious to know. I haven’t spoken with Brady Corbet about it, so the only answer I can give is that sometimes there must be a sad ending and then a new life. But let me tell you something funny. My very first office in Milan was a brutalist building, the Torre Velasca. It’s a fantastic building, but it breaks the rules.

That’s a wild coincidence.

And there are other coincidences. The arpeggio of the song was played by an American gentleman who is a pianist but has also been the Golden Globes music conductor for the past two years. That’s funny, right? Because now the movie has won a Golden Globe award. And the drummer on the song was Keith Forsey, an Oscar winner for Best Song for “What a Feeling” from Flashdance.

Can you tell us more about the process of recording the song?

My brother and I recorded and produced music for 55 years. We had a recording studio, which was used by very famous artists like Depeche Mode, who recorded Violator there, and Robert Palmer, who recorded Heavy Nova there. Even Lady Gaga came in for a short time. We started our career in Munich — we wanted to get out of Italy because they were too narrow-minded about music. They just wanted Italian bel canto music. When we were recording our first dance album under our own name, La Bionda, we were also writing film scores and working with Sergio Corbucci on the very first Django movie in Rome.

Dance music is mainly bass and drums. But the bassline is very important. In our song, I found that I was singing along to the bassline. It was terrific. I said, it sounds like the words, “one for you, one for me.” The lyrics writer, Richard William Palmer-James, who was a former member of Supertramp, didn’t like it. He said, “No, it doesn’t mean anything!” I said, “I don’t care that it doesn’t mean anything.” People don’t need to understand. He’s got a bachelor’s of English literature, so, you know. But this song was just a way to reach all the people who are sitting around in a crowd. And when the song comes on, they all come up and dance.

It’s really does make you want to move. Italo-disco music has gotten pretty popular again in recent years — is that something you’ve noticed or heard about?

This song is evergreen. I hear that it’s played in clubs, I hear it’s playing on summer vacations. I’m not surprised. But to clear up one point, La Bionda weren’t the ones who started “Italo-disco.” The scene started after us. This song is a pop song recorded in Munich with all the stuff that was used to record other pop songs at the time.

So you’d just call this a disco song.

Right, it’s a dance song, at the time you’d say “disco song.” But not “Italo-disco,” that was something where they needed afterwards to put a label on the shelves. Where should we put these records? People need classification.

Has the movie drawn a lot more attention to “One for You, One for Me”?

It is absolutely getting more plays and views now because of The Brutalist. I’m not surprised. We always paid attention to our productions. We had another world-famous hit called “Vamos a la playa.” We produced it in Spanish, because the Spanish language is spoken all around the world. So we had a couple of Italian guys singing in Spanish and it was a huge hit single. We like to appeal to the world. With the cost of production, why not try to get the world, and not just Italy?

Your brother passed away in 2022. What do you think he would have thought of all this?

It’s a very nice question. I know my brother would be happy. I’ve experienced so much in my life. But I’m so happy now that my music is part of such an important film.

Life might get crazier this weekend if your song ends up in an Oscar-winning movie.

I’m sure it will. I’ll be toasting to these beautiful people, Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold, who made this film for which I’m very grateful for being a small but important part. I thank God, I thank everybody.