This article was originally published December 23, 2024. At the 97th Academy Awards, Adrien Brody won the Oscar for Best Actor.

Adrien Brody has stopped to contemplate a pile of cardboard. We’re walking through London’s West End, where he’s doing a play, when he spots a few dozen broken-down boxes splayed out on the sidewalk. “That’s a great breakdancing platform. That’s a gold mine,” he says. “It’s also a village.”

I wait for him to explain. In the couple of hours we’ve spent together, I’ve come to learn this is how Brody’s mind works, leaping between seemingly unrelated things. Just an hour before, the metallic thunk of a mailbox lid triggered a line from his play, The Fear of 13, spoken when his character, a death-row inmate, receives a letter. And the cardboard sent him down a rabbit hole of the time he went scuba diving without a license when he was 23. It was the night before he left Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, where he had been shooting Terrence Malick’s war movie The Thin Red Line. “I’d spent six months playing a guy who’s feeling inadequate because of his fears,” he says. So he dove into the sea to survey the wreckage of massive Navy ships sunk during the Pacific War to prove he wasn’t chickenshit. “That was me being very foolish and young.”

Oh right, the cardboard.

On Guadalcanal, many of the residents lived in homes made from cardboard boxes. The pile reminded him of an encounter he had with a young boy there. Brody had put on an outdoor hip-hop show with one of his co-stars, Dash Mihok; they called themselves the Thin Red Liners. Afterward, a boy, around 8 years old, came up to him and asked if Brody could buy him a coconut. He did, and they got to talking. Brody asked why he wasn’t at school, and the boy said his uncle had him gathering boxes during the day for shelter. Brody made a commitment to pay him a few hundred dollars a year so he could go to school. (The boy then brought his friend who wanted in on the deal.) His co-star Mickey Rourke (cut from the final edit of the film) liked the idea, and the two of them wound up paying for the boys’ education through high school. “I forgot that story for a long time,” Brody says. “Ten stories deep looking at a pile of cardboard.”

In This Issue

Brody is 51 years old now, but he remains guileless in a way that can catch you off guard. He doesn’t talk in sound bites. He’s pensive and earnest and lets his thoughts go where they may, like a dog off leash. Stories meander but return eventually. This may partially explain why for all of his prodigious capacities as an actor, Brody has not been particularly good at being famous. His girlfriend, the fashion designer Georgina Chapman, tells him he’s bad at hiding it if he doesn’t like something or someone. “She’s like, ‘You’re an actor, darling. Why can’t you?’” To which he says, “It’s very hard unless I work to believe it.”

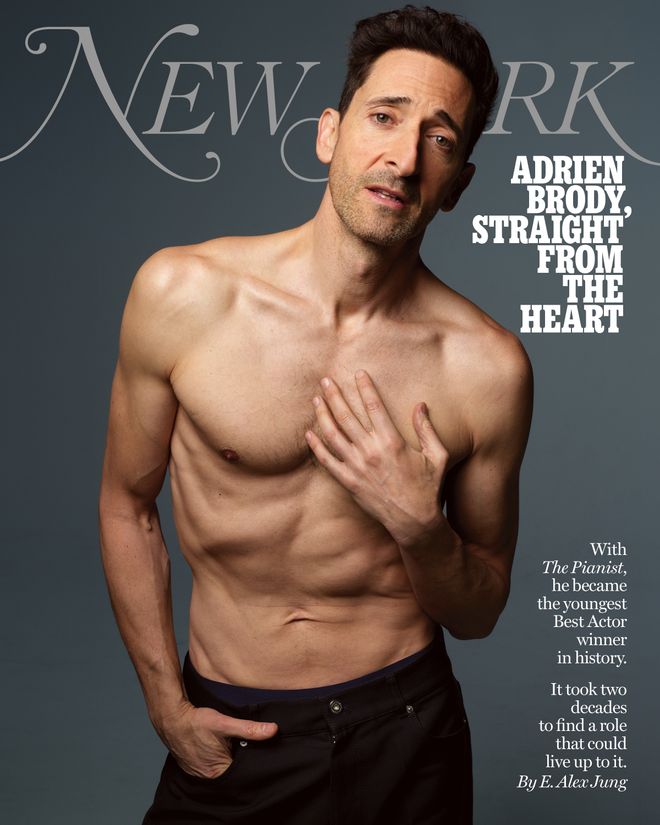

Ever since Brody became, at 29, the youngest Best Actor Oscar winner in 2003, for Roman Polanski’s The Pianist, he has felt of a different time and place — sexy in a European way with a promontory of a profile and angled eyebrows that would have made Rodin weep. In the years after his Oscar win, Hollywood never knew quite what to do with him. Early on, he was compared to Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, but he never got parts like them. (One wonders how a young Brody would have fared in this contemporary era of waifish leading men.) He knows he’s not for everyone — his mien, his carriage, his seriousness. He’s a specific man for specific tastes. “I accept what I am and who I am,” he says. “A lack of specificity can get you more work in a leading man’s space, but it is the specificity of character that makes human beings so interesting.”

Brody has found such a personage again with Brady Corbet’s film The Brutalist, in which he plays László Tóth, an uncompromising artist in compromised times. The film begins with Tóth, a fictional Bauhaus-educated Jewish architect, arriving in the States in 1947 after escaping the Holocaust. He has left behind his life in Budapest, where his buildings stamp the cityscape. He arrives in Philadelphia to work at his cousin’s furniture shop, where his curvilinear Marcel Breuer–esque designs are out of step with the local fashions. Eventually he finds favor with Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), a blustering industrialist who wants him to build a community center named after his mother on the grassy hillside in nearby Doylestown. Their egos meet at this point of ambition.

Tóth struggles with Van Buren’s whims but must maintain the artist-patron relationship in order to see the project through. There are delays, unforeseen costs, and skeptical townspeople; he sacrifices his compensation to stay true to his vision. At one point, an architect best known for building shopping malls is, to Tóth’s outrage, brought in as a consultant. Tóth is of a singular mind but also rude, petulant, warm, funny, and tormented by his past. Corbet has called The Brutalist “a movie about making a movie,” and it’s easy to transpose Tóth’s quest onto the act of filmmaking itself. The Brutalist has an epic sweep, filmed in VistaVision with a three-and-a-half-hour run time and a 15-minute intermission. Corbet went on his own circuitous seven-year journey to arrive at this point, derailed at the start of the pandemic when he had an entirely different cast, only to refinance the project with a new group of actors. Tóth is Corbet is Brody is any artist attempting to create something indelibly theirs.

Doing a work of this scale makes Brody conscious of how finite life is and what he hopes to leave behind. The Brutalist is a stirring reminder of the Adrien Brody we’ve been missing. Some faces can take a lot of makeup; his can bear the weight of history, built for epic narratives about art, immigration, and war. The Pianist, in which he played Władysław Szpilman, the acclaimed Polish musician who survived the Holocaust, is a spiritual predecessor to The Brutalist: Where Szpilman lives through a genocide, Tóth toils in its long shadow. And as with The Pianist, Brody could get an Oscar nomination and maybe win again. “Look how long it’s taken me to find another real pillar of work that I want to leave behind,” he says.

I first meet Brody after an evening performance of The Fear of 13 at the Donmar Warehouse in November. He plays Nick Yarris, a real-life man who was wrongfully imprisoned in 1982 and spent 21 years on death row. Brody has changed into a gray sweater and sweatpants; his hair is still damp from a shower scene. When I arrive at his dressing room, he gives me a hug, saying, “I’m happy to give you as much as I have.” His agent Ben Dey is there, along with Chapman. Brody met Chapman in 2019 through a mutual friend on a trip to Puerto Rico. “She talks me into most things,” Brody says, including this play. There was a matinee earlier, so he has been here all day. “This is my little prison,” he says, pointing to the blue cot on the floor. He usually doesn’t go out, preferring to eat something from home. After the matinee, he’ll meditate and take a nap. When it’s time to start amping up again for the second show, he’ll caffeinate, take a lion’s-mane mushroom supplement, and do some push-ups while listening to trap music. Then he’ll bring it back down with something sad and slow (today that’s John Frusciante’s “The Will to Death”).

The Fear of 13 is the first theater production Brody has done since he was 12, when he was in Joan Schenkar’s play Family Pride in the 50s at Theater for the New City. He felt enormous pressure to pull it off. During opening week, he would just lie there thinking about Iwao Hakamata, a Japanese man who was recently acquitted after spending 58 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. He and the playwright, Lindsey Ferrentino, went over every line. They learned they both had a habit of adding “ass” as a suffix, as in dumbass, smart-ass, smug-ass, etc. During rewrites, she tweaked the language to sound more like him. “There was no distance between my idea of what this play and character was and what his idea was,” says Ferrentino.

The intimacy of the 251-seat black-box theater plays to Brody’s strengths. As in The Brutalist, Brody traces the arc of a man’s life, and he fills Yarris with a charismatic, wisecracking verve. There are scenes in which he is a hapless teenager again, doing meth and stealing cars, and his body morphs into the noodly physicality of youth, then those in which he collapses under the crush of the bureaucratic nightmare of the legal system. Tonight, before he came out for the final bow during the standing ovation, he went to the bathroom and cried. “I just needed to fall apart a little,” he says. “The hard thing is to get back up onstage when people are applauding. I don’t enjoy it. It’s very weird because at the end of that I just need to go away.”

When he’s not working, Brody lives a nomadic existence, he says. In London, he has been living a monastic one. When he arrived, he spent one month living in the attic apartment of the Donmar’s rehearsal space. He would wake up, stretch, and head to the basement to work. Afterward, he’d go for a walk or swim, then go over his lines again. On Sundays, he was the only person there and would sometimes set off the alarm when he went outside. Once the run started, he sublet an apartment in Islington.

I visit Brody there a few days later. He comes to the door dressed in a white T-shirt and jeans, holding incense. He keeps the temperature of the place warm, and we go down to the garden level, where he makes us green tea before we settle on the floor around a stone coffee table that he calls “very Brutalist.” He lights the stick of copal, balances it on a fork, and sets out some dried mango. There’s a window slightly overhead where pedestrians flit past. A subtle, woodsy scent fills the air. As we’re talking, the gray silhouette of a man stopping to look at his phone appears against the window shade. “Where’s my camera?” Brody says, gazing up. “Fuck, it’s over.” The man has walked away; the moment is gone.

His mother, the photographer Sylvia Plachy, would lug five cameras around for this very reason. (If you stay ready …) This is how Brody thinks about his own work, which is to have the tools to weather any challenge on set: mechanical error, limited time, fading light, sudden noises. In some ways, he sees his job as being a timekeeper, imprinting this sliver of the present into film so it can exist in the future. Sometimes you have only a few minutes. “The gift of finding that one moment amid the 15 minutes you have to really get it, and the knowledge that if you did not discover it within that window would mean that it was never discovered,” he says. “It’s never going to be discovered. It’s never going to be something you can go back and reclaim.”

Discipline, rigor, pain are all in service of catching the moment. When he filmed The Jacket, a sci-fi thriller in which he’s sent to a mental institution, he told the director to leave him in a straitjacket so he could get a feel for it. He broke his nose when someone accidentally punched him in the face during the filming of Summer of Sam, giving him a permanent dent. For Oxygen, in which he plays a serial killer with braces, he got actual metal ones instead of prosthetics. “I didn’t know how fucking painful that was until they stuck in pliers and ripped them off my teeth at the end,” he says. For Wrecked, he ate ants and worms (his character wakes up alone in the woods).

But for no movie was there a greater physical toll than The Pianist. Six weeks before the shoot in Germany, he shed his material possessions, selling his car and getting rid of his apartment and phone and putting his things in storage. They shot in reverse so the film would begin with Szpilman at his most depleted. Brody put himself on a near-starvation diet, eating small bits of protein while practicing Chopin for hours. He lost 30 pounds, dropping to 129. He and his girlfriend broke up. He was barely drinking water by the time they started filming. “That was a physical transformation that was necessary for storytelling,” he says. “But then that kind of opened me up, spiritually, to a depth of understanding of emptiness and hunger in a way that I didn’t know, ever.”

The aftereffects were long. He had insomnia and panic attacks. I ask if he feels like he has PTSD from the experience. “I do, yeah,” he says. “I definitely had an eating disorder for at least a year. And then I was depressed for a year, if not a lifetime. I’m kidding, I’m kidding.”

Brody has an acupuncture session in the rehearsal building in about an hour, so we head to the tube. He begins telling me about the time he got on a gas-powered GoPed scooter to attend the premiere of his movie Restaurant at Lincoln Center. As he’s pulling up a photo of the GoPed on his phone, we miss our stop. We get off and double back in the right direction. I ask him how he’s thinking about being back in the whole Oscar dog and pony show again. He pauses. We’ve arrived at our destination. “Well, you asked me a zinger and then we get to the stop,” he says. “I think the better question is how — if it does run the course — can I learn from my mistakes? To help ensure that it doesn’t take so long to get to be considered for the rare, really meaningful works.”

After The Pianist’s debut, Brody didn’t work for about a year. “I don’t think it was a voluntary break,” his father, Elliot Brody, tells me. “He had just won the Oscar, but he wasn’t getting anything that was commensurate to what he had just done. So he turned down a lot of crappy roles.” Adrien also felt the weight of expectation. “I do admit the bar was high,” he says.

Over the next few years, Brody eventually signed on to films with major directors: King Kong with Peter Jackson, The Brothers Bloom with Rian Johnson, The Village with M. Night Shyamalan. He began a professional relationship with Wes Anderson starting with The Darjeeling Limited that continues to the present. He did Predators, the 2010 attempt to reactivate the franchise. He had initially been offered the role of Edwin, a doctor who appears out of place in a group of professional killers, but he wanted to play Royce, the tough, taciturn mercenary — and leading man. Brody wrote the producer Robert Rodriguez a letter politely declining the part of Edwin and arguing that he could play the protagonist instead. “I said, ‘Look, there are many ways you can go with this. There’s an obvious way, and this is not an obvious way,’” he recalls writing. “ ‘If you open up Time magazine and you see soldiers, they don’t look like Schwarzenegger. They don’t look dissimilar to me. It’s about an emotional and intellectual hardness.’” He convinced Rodriguez, who then convinced the executives at 20th Century Fox to say “yes.”

Pitching himself for Royce was an attempt to change the perception surrounding him. (Predators did fine but not well enough to green-light a sequel.) Comedy was another area. He took on broad, off-kilter roles, like a drug dealer named Psycho Ed in the stoner comedy High School and Flirty Harry, a cop who speaks in gay double entendres in InAPPropriate Comedy co-starring Lindsay Lohan, both of which grossed less than $250,000. (The latter has a 1 out of 100 on Metacritic.) “I thought I desperately wanted to do comedic work,” he says. “And that was another limitation, because I’d only really done dramatic work and nobody thought I could be funny.”

The year of his Oscar win, Brody hosted Saturday Night Live. He introduced musical guest Sean Paul by putting on a dreadlocked wig and a jittery Jamaican accent. He entered that week with a slew of ideas, including that one. “They were all literally agape from me pitching,” he says. But SNL got him the costume and he did the bit during the dress rehearsal. “I think Lorne wasn’t happy with me embellishing a bit, but they allowed me to,” he says. “I thought that was a safe space to do that, weirdly.” There were rumors that he had been banned from the show, which to his knowledge is not true. “But I also have never been invited back on,” he says, laughing. “So I don’t know what to tell you.”

Brody is generally much more circumspect and self-conscious about what he says now. He’s reluctant to relive his more off-the-cuff celebrity moments. He’s dismayed when I ask about the infamous moment when he spontaneously kissed Halle Berry on the Oscars stage and declines to say anything about it. (That year, he told GQ that it was “a big, beautiful thank-you.”) Politics is another third rail. The formation of the State of Israel coincides with the events of The Brutalist; some of its characters decide to move there. Brody’s 2003 Oscar win came a few days after the U.S. invaded Iraq. In his speech, he said, “Whomever you believe in, if it’s God or Allah, may He watch over you. And let’s pray for a peaceful and swift resolution.” This awards season arrives squarely during Israel’s ongoing bombings throughout the Middle East. He gives a similarly diplomatic response when I ask him about the destruction in Gaza. “I am opposed to injustice and opposed to all the horrors that are around us,” he says. “And I feel for people who are victimized by these things that are much bigger than us.”

In the 2010s, his career miscalculations began to accumulate: His movies weren’t making money. “I’d rather not go down the list of what movies in particular I felt were disastrous,” Brody tells me, but he says he tried to follow the same criteria he always has with scripts: Is it different? Do I like the director? Will this be fulfilling? He took chances on first-time directors, like Michael Greenspan for the thriller Wrecked, in which he plays an unnamed man who survives a car crash. Critics would say he gave his all in a bad movie. (“Brody’s engagement with the material prevents Wrecked from falling apart,” wrote Eric Kohn.) He made a foray into the Chinese market with Dragon Blade, starring alongside Jackie Chan and John Cusack. What he learned from this time was that “you don’t have the creative freedom to be as experimental in an artistic way in an industry that has rules. I was not really conscious of that, and it still somehow doesn’t compute.”

All of this made him feel the yoke of the business side of Hollywood, how an actor becomes more or less valuable according to their box-office receipts. “In any film where there is an investment, they start with lists,” he says. “You’re on a list or you’re not on a list. If you are fortunate enough to predominantly do movies that make money, you are very high up on that list. And if you do wonderful, artistic, more avant-garde work, you’re way down on that list. To be A-list, you must generate income, and that relates to my concern that that erosion of values could be a permanent erosion of me on a much deeper level. Not just, Did I do a shitty movie? ”

Somewhere along the way, Brody began to feel that erosion. Around 2018, he took a break. He focused on one of his first loves and began to make art again, painting in a style that crosses Robert Rauschenberg and Jackson Pollock. “I just stepped out,” he says. “That helped me recalibrate.” After he had spent a few years away, Chapman helped convince him to go back. She told him that holing up and painting wasn’t a solution, even though it might feel like one. So he gradually made his return, popping up on shows like Succession and Poker Face and continuing to appear in Wes Anderson’s ensembles. “She helped me realize that it would be a loss to let the frustrations interfere with pursuing what I am destined to do with an open heart,” he says.

It was during that break, in 2019, that Corbet first met Brody to discuss The Brutalist. Corbet ended up casting Joel Edgerton. Then COVID shut the production down, and by the time the film was up and running again, Brody was back in the game. “I was sort of haunted by our initial discussion,” says Corbet. “I hadn’t spoken to anyone who understood the film inside and out. It’s a pretty short list of people that have the background that Adrien has.”

One reason Brody connected to the film was his mother. Plachy was born in Budapest, where the film takes place. Her mother was Jewish, and her father was Catholic. Nearly all of her relatives on her mother’s side died in concentration camps during the Holocaust. The experience of doing The Pianist fed directly into Brody’s understanding of Lázsló Tóth. Chronologically, the film picks up where The Pianist left off. Lázsló has escaped the camps, but he carries the experience with him. He’s anguished over his separation from his wife, Erszébet (Felicity Jones), only to shut her out when they reunite; he cheats on her with a woman in a brothel and self-medicates with heroin. Corbet says he wanted the character to push back against the idea that “we can only empathize with someone who’s been through a terrible trauma if they have a heart of gold.”

The experience was less intense than The Pianist. That movie was a six-month production, while The Brutalist was shot in a fraction of the time. “The Brutalist broke some illusion of the need for suffering to extend beyond what I need to conjure up the character,” Brody says. “It was surprising to me that I didn’t need to take home so much of my own anguish.” There’s a small moment in the film when Tóth is eating an apple and drawing the institute he’s building. “I said, ‘Adrien, we’re cutting,’” says Mona Fastvold, Corbet’s partner and collaborator, who co-wrote the script and shot second unit. “And he’s like, ‘I’m not quite done drawing it yet.’” It wasn’t Method acting, exactly. It was Brody, the painter, just sitting on a hillside in the sun, lost in the moment.

In December, Brody takes me to see his parents. He’s in New York for a little more than 24 hours, which happens to be the day he wins an award from the New York Film Critics Circle. His play just ended its run, and he’s fully diving into awards season — an unforgiving time for digressive thoughts. “Being asked superficial questions like ‘This is a precursor to the Oscars …’ I don’t want to even think on those terms,” he says. “I just am too serious, and I know I’m too serious.” He’s eking out as much time as he can with his parents: He took them to the Gotham Awards the previous night, and they’re going to drop him off at the airport when he leaves for L.A. later this evening. We’re heading toward Woodhaven, Queens, now, where they still live in the house he grew up in, a white single-family structure with a driveway where he would build muscle cars. They moved there from Jackson Heights when he was 4 years old, around the time that his mother, a photographer for the Village Voice, received a Guggenheim fellowship. His father, a retired schoolteacher who studied philosophy and social sciences, taught middle school in Jackson Heights. Brody has his father’s nose and his mother’s eyes.

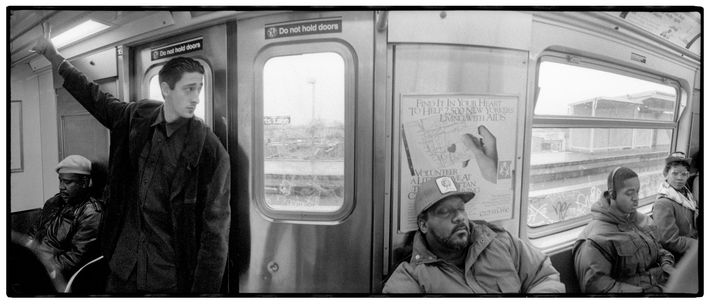

On the drive, he recounts his childhood like an urban Huckleberry Finn. He liked hanging out with the older kids. In Forest Park, they would sled down ravines on top of car hoods. He made fishing lines out of dental floss and safety pins and used bits of raw Pillsbury dough as bait to catch fish in ponds. He and his friends would see double features at a movie theater called the Drake, where his dad once caught him smoking cigarettes in the front row. It could also be rough. He got jumped for having a rattail. A kid he knew in the fourth grade got shot in the throat over a gold chain. “In retrospect, it’s been good for me. It’s made me who I am,” Brody says as we get out of the car and take a walk along Jamaica Avenue. “But New York is a hard city. It’s made me reactive in a way I don’t love but felt necessary at that time.”

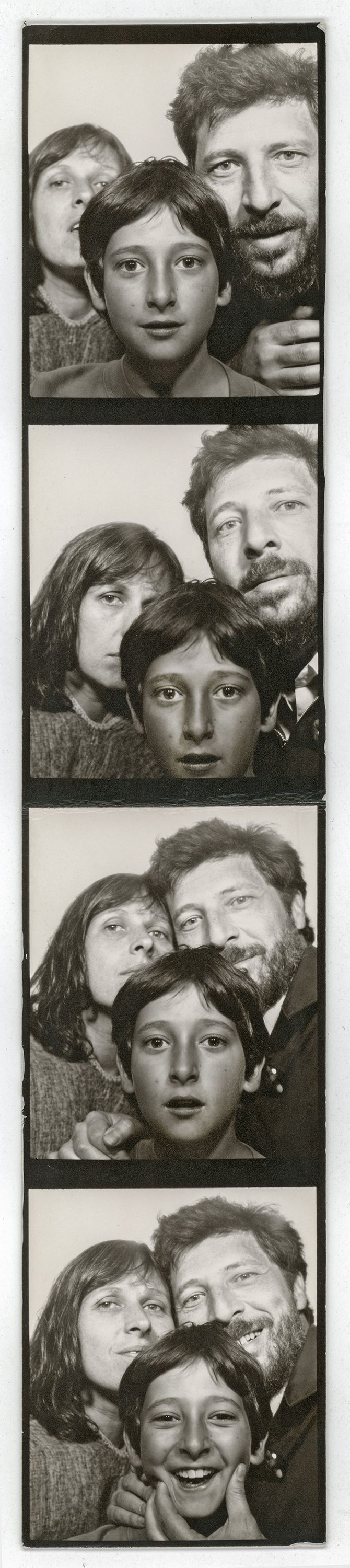

We turn toward his parents’ house, and he gives them a call to ask if it’s okay that we stop by. When we arrive, his mother is feeding some stray kittens in the backyard and his father is washing Tupperware containers and laying them to dry in the dishwasher. They fix me a coffee and show me around their house. Framed art and photographs cover nearly every inch of the walls, including paintings by both Brody men. His parents have been together for 62 years, and Adrien is their only child. On the living-room mantel sits his Oscar. Plachy pulls out photos she has taken of him over the years. When he was a baby, she made comic strips about the funny things he would say. She told friends she planned on eventually making a book of photos of him. (She’s still planning on it.) She recalls that people would tell her, “Who’s going to be interested in your little boy growing up?” She laughs. “Well, little did they know.”

When he was a kid, Plachy took Adrien along with her on assignments, like when she covered gallery openings or shot Jorge Luis Borges. When he got older, he’d still tag along. They went to the World Trade Center together the day after 9/11. He learned to be attentive by looking through her lens. “You look for things in a way that people don’t look,” he tells her. “You were very keyed in and present. And I was alone with you all the time watching that. I became very keyed in and present.”

He began acting at weekend classes for kids at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts when he was 12. He got an agent and quickly booked a couple of theater roles in the city. Even then he seemed to gravitate toward heavy subjects; his first film was Home at Last on PBS, in which he plays a New York City orphan who is adopted by a Nebraskan farm family in part to provide indentured labor. Brody’s parents have visited him on shoots around the world, including the one for The Brutalist, where his mother took photos. In her book, Self Portrait With Cows Going Home, there are pictures of him on the set of The Pianist. “He was an apparition of my father as a young man,” she writes. “How thrilling and disturbing when your own son can conjure up ghosts.”

The way Brody speaks in The Brutalist reminds his parents of Plachy’s father, who pronounced English with a thick Hungarian accent. Brody was 7 years old when his grandfather died, but the memories of his speech and mannerisms left their mark. Lázsló’s voice was the most important part for him to get right. He worked with a dialect coach and listened to how Hungarians from that time period spoke. “I knew when it felt truthful and when it didn’t,” he says. “The Hungarian sensibility, sensitivity, and strength is a quality beyond language that is noticeable to me, that is present in that character.”

When Brody talks about the responsibility to represent in The Brutalist, he means this house with these two people and the entire family genealogy that brought him here — far away from cynical business decisions or red-carpet cameras. The winter sun is gone, but before I leave, Brody, sitting on the small sofa in the living room, tells a story. During The Fear of 13, he says, he had a keen sense of time. He knew when the show went three minutes over. In his final monologues as Nick Yarris, Brody breaks the fourth wall and tries to find people in the audience to speak to directly. Sometimes the intimacy is too much, and they look away. Others will give him the energy he’s looking for.

He learned that when he let the emotion flow through him naturally, he could control it like a spigot. “That’s when I feel really alive, when you’re tapped in and you’re just modulating the flow and the force of that emotion,” he says. In his last speech, Nick recalls a gorgeous sunny day when people are outside, completely free of the knowledge of an impending storm. The whole thing is a metaphor for the kind of childhood innocence that exists before something irrevocable happens, as it does to him. Brody begins to recite the final lines of the play, when the clouds darken and nobody had thought to bring an umbrella: “We all stand on that precipice. We look up at the sky together … hoping the rain will never come … and …”

When he was fully in a flow state, he could hold back the tears so that they fell on the last word before the lights cut out and the music swelled. This happened only once, maybe twice, during the entire run of the show, but that split second helped him understand why actors do theater. It’s not like a film, which you can pause and rewind. The ephemerality is the point. “To do an hour and 47 minutes and, on the one hour and 47th minute, control a thing exactly that is actually a real emotion within you, connected to it and channeling it and peripherally feeling every person there hanging on that last breath, the power and the feeling and the … It is so fucking beautiful.”

As he’s speaking, I look at his parents, who are completely rapt. They’re his audience tonight.

More on ‘The Brutalist’

- Guess How Long Adrien Brody’s Oscars Speech Went

- The Death of the Classic Film Score

- Oh No, Halle Berry and Adrien Brody Kissed Again