“If you are there influencing the very fact of it getting made,” the documentarian Ken Burns told the Wall Street Journal by way of explaining why he isn’t watching The Last Dance, “it means that certain aspects that you don’t necessarily want in aren’t going to be in, period.” In lieu of heartier and more nourishing fare, documentarian beef is what’s for dinner, but Burns has a point: Michael Jordan indisputably exerts that influence over The Last Dance. As a result, the series can feel like one of those ambiguously advertorial authorized biographies that famous people offer when they want to appear open and fearless. The voice of the narrator changes, but the mediation and sanitized-for-your-protection experience doesn’t.

The distance between that experience and anything more revelatory is why the weekly hype cycle surrounding The Last Dance can come off as grating. “There’s language in there that I’m shocked that ESPN let us keep in,” Hehir said of this episode on The Dan Patrick Show last week, “And there’s behavior in there that I’m shocked that Michael let us keep in.” The wording of that last clause—the very presence of “Michael” in it—does a lot to undermine, if not entirely undo, the “shock” part. And yet it doesn’t undo what works about The Last Dance. The trick, I’ve come to think, comes down to how we watch what Jordan and Hehir show us.

“Episode VII,” like the other better parts of the series thus far, spends a little time with the Bulls’ slog of a title defense in the ‘97-98 season and a lot more time shuttling back into the past for context and color. This is useful not because it shows us much new about the Last Dance season—the vaunted never-before-seen footage has mostly come up empty—but because it explains how and why the greatest of basketball dynasties wound up so sour and conflicted. Those trips back in time have served to tell Jordan’s story, but there’s no way to tell the story of these Bulls, their success, or how much it wrung out of them without him.

The more team-oriented parts of The Last Dance work as straightforward and intermittently thrilling sports storytelling. In “Episode VII,” the basketball bits are about the team’s modest struggles with the New Jersey Nets in the first round of the ‘97-98 NBA Playoffs—as a fan of that Nets team, it would be unethical to write anything more about them, but my DMs are open to any and all Sherman Douglas-related questions—and Chicago’s intermittently stormy but mostly successful first Jordan-free season in ‘93-94. It’s all done well, although what Hehir shows us of supernova Scottie Pippen and a slick, early-career Toni Kukoc again feels tantalizing and too brief. But there is only so much time and this is Jordan’s show. On film as on the court, his presence means fewer touches for everyone else.

It’s the Jordan stuff that requires a bit more flexibility from the viewer. Besieged by questions about his gambling—in deference to Jordan’s phrasing from the previous episode, we can just call it his Competition Problem—and grieving the senseless and seemingly random murder of his father James in the summer of 1993, Jordan retires after the team’s third straight championship and pursues his original sports aspiration. Jordan was 31 years old at the time and 14 years removed from his last baseball game, but Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf happened also to own the White Sox, so he was willing to give his exhausted star a spring training invite and then a minor league roster spot, at his full NBA salary, to chase that old dream. Jordan’s performance at Double-A Birmingham was both objectively poor and astonishingly good: He hit .202 with virtually no power, but he also hadn’t played baseball in 14 fucking years and stole 30 bases just a couple of rungs down the ladder from the bigs. Various talking heads opine about how happy Jordan was in his year away, and Hehir shows us his subject smiling and high-fiving and seeming altogether more sunny-sided than he has in any basketball-related footage. Because Jordan is Jordan, a Sports Illustrated cover that showed him missing badly on a breaking ball with the headline “Bag It, Michael!” is mentioned, as is the fact that Jordan never spoke to Sports Illustrated ever again.

There was speculation at the time that Jordan’s retirement was not a retirement at all, and that he was serving a gambling-related suspension issued in secret by the late NBA commissioner David Stern. To say that The Last Dance dismisses this would be an understatement. Jordan, Jordan’s biographer, a host of talking heads, and finally Stern himself all take turns explaining how preposterous and obviously false the Secret Suspension theory is. None of the above is necessarily gripping cinema on its own, but the obviousness of it is useful in highlighting the points that Jordan wants underlined and the broader story he wants to tell. It’s also useful at showing us how Michael Jordan understands his own story.

But none of that was what Hehir was referring to when he talked about the stuff that he was surprised Michael allowed him to keep in the final cut. That all falls in the last and most interesting third of the episode, which engages the often-asked question—Was Michael Jordan An Asshole?—and concludes with a tearful Jordan and a resounding “well, it’s complicated.”

In the ways that matter, it’s not. That Jordan was an abrasive, abusive teammate has been a matter of public record for going on three decades, and hasn’t been a secret even in this extremely reverent and carefully managed re-telling of his story. The ostensibly shocking footage is precisely what anyone familiar with Jordan would expect: many curse words, idle hazing of lower-status teammates, and some shit-talking. Jordan justifies every egregiousness in the way he always has, which is that he was only This Way because he wanted to win, he needed his teammates to get on his level, and that this was his way of getting them there.

We can only ever take his word for it, but that doesn’t mean we have to take him literally. We again see Jordan riding Scott Burrell, in practice and after games, and then explaining that he felt it was important to do so to toughen Burrell up. There’s a simpler explanation for how Burrell became a target, though: He was Jordan’s backup and often his opposite number in practice. Burrell was traded from Golden State to Chicago before the ‘97-98 season and was at that point in his fifth NBA season; after two productive years as a starter in Charlotte, he was entering the back half of a career in which he’d mostly be a role player. He played 13.7 minutes per game with the Bulls, which made him the tenth man in the team’s rotation. “Episode VII” shows him shooting the lights out in the game that ended Chicago’s first-round series against the Nets, which [redacted]. But while Jordan says that he spent the year trying to toughen Burrell up, there was no clear strategic or leadership-related reason for Jordan to single him out for punishment. He just wasn’t an essential player, and the team would release him at the end of the season. It seems more likely that Jordan couldn’t help—and despite coach Phil Jackson’s urging, couldn’t really be stopped—trying to humiliate whoever was in front of him.

Jordan talks about trying to get Burrell to fight him, and being vexed by Burrell’s capacity to laugh him off. But Burrell was just another bit player in Jordan’s singular lifelong quest to mint rivals whenever and wherever required. Everyone that played with him understood that Jordan was just like this—an implacable bully who was also the greatest and hardest-working basketball player on Earth. “Let’s not get it wrong—he was an asshole, he was a jerk,” former Bulls center and frequent Jordan target Will Perdue says, “He crossed the line numerous times. But as time goes by and you think about what he was trying to accomplish, yeah, he was a hell of a teammate.”

This has long been the official story on Michael Jordan, The Teammate. Many people who more or less hate Jordan, with ample reason, also own NBA championship rings thanks to him. They’ve made their peace regarding what Jordan took and what he gave. In “Episode VII,” Jordan tries to do the same. ”I pulled people along when they didn’t want to be pulled. I challenge people when they don’t want to be challenged,” an emotional Jordan says, a notably full rocks glass at his right hand. “Now, if that means I had to go in there and get in your ass a little bit, then I did that … You ask all my teammates, one thing about Michael Jordan was he never asked me to do something that he didn’t fucking do.”

For what it’s worth, none of Jordan’s former teammates argue with that point. The bigger question the episode asks is whether it was worth it. “Was he a nice guy?” former Bulls guard B.J. Armstrong says. “He couldn’t have been nice. With that kind of mentality he had, he couldn’t be a nice guy.” Everyone but Jordan has long been content to leave it there.

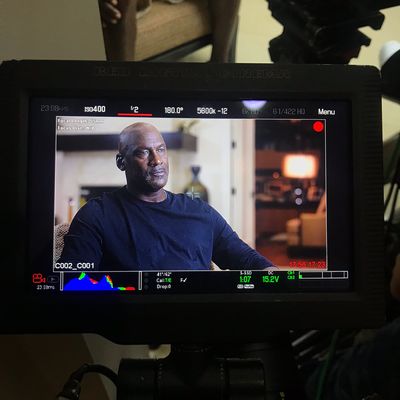

Jordan being Jordan, though, and this being his show, he presses his case. It’s another loss he just can’t accept. “When people see this, they’re going to be like, Well he wasn’t a nice guy, he might’ve been a tyrant,” Jordan says, his glass again topped up. “But that’s you, because you never won anything. I wanted to win, but I wanted them to be a part of it as well.” Hehir here gives us big swelling music over various images of Jordan triumphing. “Look, I don’t have to do this,” Jordan says. “I’m doing it because this is who I am. That’s how I played the game. That’s my mentality.” He starts, at that moment, to get choked up about how committed he is. “If you don’t want to play that way, don’t play that way.” And then he calls “break” and leans forward out of frame. And Hehir cuts, just where Jordan tells him to.

Want to stream The Last Dance? You can sign up for ESPN+ here. (If you subscribe to a service through our links, Vulture may earn an affiliate commission.)