In a different cultural moment, The Last Dance’s luxuriously upholstered running time would feel very different, but also in that different cultural moment we would not all be watching The Last Dance right now. These episodes were originally slated to run after the NBA Finals, and then rushed into the programming vacuum created by the suspension of everyday American life. There hasn’t been much in the first five hours of The Last Dance to suggest that there need to be five more hours of The Last Dance, but “extenuating circumstances” barely begins to explain how a nation of NBA-deprived homebound basketball weirdos came to rely on The Last Dance as the last remaining link to The Before Times. It wasn’t supposed to be this way, but also that’s a very long list.

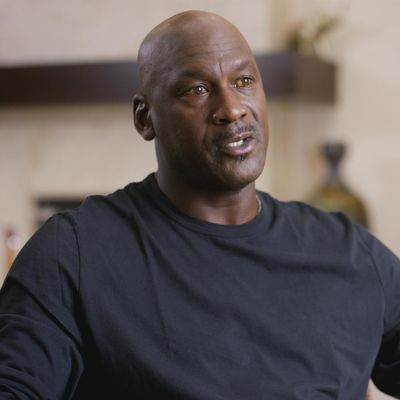

And anyway, we can only watch it from within this uneasy, unfinished moment. Halfway through, it’s clear what The Last Dance is and is not: The basketball stuff by and large is great, Michael Jordan is as good at carrying grudges as he was at playing basketball, it’s much more enjoyable to watch him doing the latter than the former, and it’s a lot more fun than it is important. The flabby or slipshod or stan-brained parts can also at least partially be explained by the fact that The Last Dance is even now very much still a work in progress. Arash Markazi of the Los Angeles Times reported that director Jason Hehir was still interviewing subjects six weeks ago, when the NBA season was suspended; the second-to-last episode was just finished two days ago. The hyped, hopeful comparisons between The Last Dance and Ezra Edelman’s similarly sprawling but infinitely more sophisticated and technically masterful O.J.: Made In America were pretty much instantly revealed to be fraudulent, but circumstances have also conspired such that many millions more people are watching something that probably only sort of resembles what Hehir originally had in mind.

But with every sport preempted indefinitely by marathon airings of The Collapse Of Everything We Ever Held Dear on every channel, The Last Dance feels like both a blessing and a mercy, despite and even because of how lumpy its plush narrative padding can feel. When it’s scattershot and petty and glib, as it was for most of its first half, The Last Dance is still better than anything else we’ve got. But when it’s good, as it was in “Episode IV” and is again in “Episode VI,” The Last Dance is tantalizing. In “Episode IV,” Hehir used the story of the Bulls figuring out how to go from The Michael Jordan Show to the NBA champions to explain how the same team wound up so exhausted and conflicted and different by the end of the decade. In this one, the story of the team’s first three-peat, which was sealed amid a tumultuous period in Jordan’s life in 1993, tells the story of how Jordan’s all-consuming competitiveness and passion for dominance threatened not just to consume him but to undo the brand he had become. The basketball doesn’t drive the storytelling quite as clearly as it did in “Episode IV,” but it helps by forcing some structure onto it.

The Last Dance has to this point worked best when Hehir’s incorrigible channel-flipping impulses and deference to Jordan himself are kept to a minimum. By sticking to a given Bulls team’s title pursuit as a framework and unpacking the complexities and challenges of that shared pursuit instead of letting Jordan sourly walk the viewer through his vast collection of treasured grievances, Hehir lets the story breathe in a way that Jordan himself just can’t. “Episode VI” delivers in those respects, and also stands out relative to the overextended previous episode as an example of what The Last Dance might have been had Hehir and his editors had time to figure it all out.

We spend some time in the Bulls’ ‘97-98 season here, but it is mostly about 1993—the year that Michael Jordan’s proud and heedless and utterly justified belief that he was untouchable finally came violently into conflict with the much simpler brand he’d built, and how the annihilating passions that made him a champion threatened to annihilate him. Hehir does well to let the various pressures bearing down on Jordan—some of them the creation of the sports media and popular culture he’d conquered, and some of them plainly the result of Jordan’s own chaotic needs and envelope-pushing recklessness—play out along the familiar timeline of a pair of NBA seasons. Both Jordan’s ‘92-93 and ‘97-98 seasons ended in triumph; the interesting part is why both of those championship seasons were also so multiply exhausted and exhausting. The reason for both, as usual, begins and ends with Jordan.

“It’s funny,” Jordan says dourly on a commercial set at the very beginning of the episode, “a lot of people say they’d like to be Michael Jordan for a day, or a week. But let them try to be Michael Jordan for a year, see if they like it.” The production clapper board identifies the year as 1992, a time when Jordan was at his zenith as both a player and a product, chasing a legacy-securing third straight NBA championship, and already seemingly wrung dry. Jordan extemporizes different twists on the line in subsequent takes, all of them landing somewhere between weariness and outright self-pity. Jordan had what he wanted most, which was everything, and yet he felt both surrounded and alone. He had been exposed as a clubhouse tyrant by beat writer Sam Smith’s bestselling 1992 book The Jordan Rules, an unsparing portrait of the team en route to their first title in ‘90-91, and was being covered in a very different way. As a player, Jordan was still undeniable, but with the extent of his competitive fetish now a matter of public record, people began to question how and how wisely he pursued the dominance that fueled and focused him.

It’s worth noting here that elite athletes are by and large all absolute competitive psychopaths, so Jordan is not the first champion who got off as much on making someone else lose as he did on claiming a win for himself. That Jordan played in high-stakes card games on the team plane is something he has in common with basically every NBA star in history; that Jordan also journeyed to the front of the plane, where rotation players with lower salaries were playing blackjack for a dollar a hand, to try to get into—and win—those games is where the difference between Jordan and his fellow psychopaths becomes clearest. “‘Why in the hell would you want to play with us?’” backup center Will Perdue remembers the veteran guard John Paxson asking Jordan when he tried to join their game, “‘We’re playing for a dollar a hand.’” Jordan’s answer, Perdue says, was “because I want to say I’ve got your money in my pocket.”

It’s one of the ironies of Jordan’s life that while his brilliance at the sport to which he dedicated his whole being made him impossibly wealthy, his unrelenting competitiveness led him to lose sizable sums of money at other pursuits at which he was not nearly as good. We see Jordan lose $20 in an inscrutable coin-tossing game to a Bulls clubhouse security guy with a crispy gray perm; the security guard hits Jordan with the same what-more-can-I-say shrug that Jordan gave after lighting up the Portland Trail Blazers in the previous year’s NBA Finals. We also see Jordan making a circuitous duffer’s route across the golf course, losing balls and winning a small bet. We learn, too, of much larger losses—like a $57,000 check for a gambling debt that the feds found in the possession of a man named James “Slim” Bouler when they arrested Bouler on drug and money-laundering charges, and the seven-figure debt that a man named Richard Esquinas claimed Jordan owed him after years of gambling on golf games. (Esquinas’s awful book about their relationship, which I read years ago, was released during the ‘93 NBA playoffs.) In that context, Jordan gambling in Atlantic City the night before a loss to the New York Knicks in Game 2 of the ‘92-93 Eastern Conference Finals becomes the subject not just of superheated sports media takesmithery—some things never change—but darker speculation about bigger problems.

Because Jordan has never stopped gambling or chasing his competitive jones, this speculation has never really gone away. Hehir doesn’t answer any of those questions—The Last Dance just isn’t that kind of documentary—but he lays them out unsparingly. We see Jordan, then and now, making the case with some irritation and also some justification that his were acceptable losses given his wealth, and not the sign of any broader problem. The first point is certainly true, and while the second is more debatable, it also feels like Jordan’s business. Jordan is pressed about his gambling by a stupendously smarmy Connie Chung in a TV interview—“You aren’t gambling with money,” she pleads, “you’re gambling with your reputation, with your good name”—and while his initial response is a textbook I Can Stop Whenever I Want whiff, his second seems much closer to the truth. “I have a competition problem,” Jordan says.

It’s an uncomfortable moment and Hehir has the good sense to leave it there. The conflict between this champion’s helplessness and invincibility helps fill in Jordan’s famous silhouette. To be that great for a week or a month would be a thrill; Jordan’s mythos is built on those very dreams of flight. To be that harsh and conflicted and unrelenting for a year, even one that ends in another championship, is another thing entirely. In “Episode VI,” you can see how you’d like it.

Want to stream The Last Dance? You can sign up for ESPN+ here. (If you subscribe to a service through our links, Vulture may earn an affiliate commission.)