Every NBA fan of a certain age has heard “Sirius” by The Alan Parsons Project more times than they can count. On its own, this seems strange, given that the 114-second British prog-rock song was never released as a single, has no lyrics, and is more an instrumental introduction to the title track on the band’s sixth album, “Eye in the Sky,” than a stand-alone anthem. It is, like so much of the work that the band put out during the late 1970s and early ’80s, “progressive” mostly in the sense that it is a long synthesizer-driven build to nowhere in particular, padded out by every bit of goofy-lush studio frippery available at the time and propelled by the band’s singular style of pill-and-powder grandiosity. The album went platinum but has nothing like the kind of afterlife that “Sirius” has enjoyed. A fan-made YouTube video for an extended mix of the song lays it all over a series of science-fiction mountain ranges and pastel martian skyscapes and faintly Egyptological crests, and has nearly 9 million views.

There is a reason for this: The Chicago Bulls have used “Sirius” as the soundtrack for their starting lineup at the United Center for nearly 30 years now, though for the last two decades the song’s recursive synths and soaring extraneous strings and obtrusively grandiose guitar line have served as the introduction to some luridly forgettable teams. The courtside announcer has said the names of Chris Duhon and Marcus Fizer and Paul Zipser and the graying 38-year-old version of Charles Oakley over that music, and for those fleeting moments in a darkened arena the starting lineup has sounded much more imposing and exciting than it pretty much ever was. With all credit where due to Alan Parsons and his broader project, it’s fair to say that all of this is because, during the ’90s, this song was what it sounded like when Michael Jordan’s Bulls were about to take the floor; for every person that cared about NBA basketball during Jordan’s sour and wondrous reign atop the sport, the song triggers a combination of reverence and anticipation as something like an autonomic response. The greatness and significance of that team is why this goofy song somehow retains its weight despite the Bulls spending most of the last two decades in peevish, stubbornly pot-bound mediocrity. “Man, every time — that song gets me every time,” Steph Curry said of “Sirius” back in 2016. The Bulls team it was introducing that year won 42 games, lost 40, and didn’t make the playoffs. The song that gave Curry chills ran under the P.A. guy putting some hopeful stank on the names of Taj Gibson and Tony Snell; Curry’s Warriors, which just edged the 72 wins of the ’95–’96 Bulls to finish with the best regular-season record in the league’s history, beat the ’15-’16 model by 31 points. And still it works.

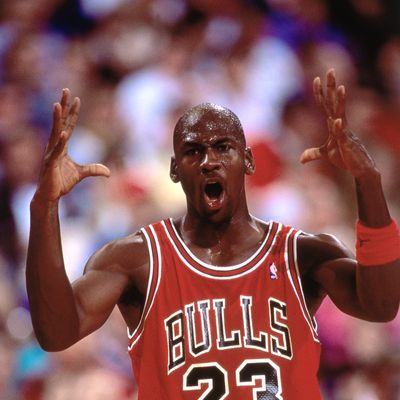

The dynastic Bulls — built around Michael Jordan, bolstered by a pair of incomparable supplementary stars in Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman and led by coach and arch-boomer executive magus Phil Jackson — were more than the defining team of its era, although there were undeniably that. Because of Jordan, who was the most famous and most brilliant athlete of his generation, those Bulls were the most important sports team on earth — not just the best and most dominant in any sport but in a more profound sense the biggest. The dynasty’s brightness and bulk pinned the rest of the league into distant orbit, and Jordan himself, both with his graceful and implacable greatness and the heavy density of his corrosive and all-consuming competitiveness, was its molten core.

The debate about whether Jordan is or isn’t the best basketball player in history has now spanned whole generations without ever quite becoming interesting or approaching anything like a conclusion. In the absence of any actual sports to talk about and given the massive anticipation for The Last Dance, ESPN and Netflix’s new 10-hour co-production on the last season of that dynasty, Twitter will be almost certainly be flooded with barbershop-grade sophistry and superheated pedantry on this topic once again, continuing for some period ranging between “the five weeks over which the series is set to run” and “until the vengeful oceans finally claim us.”

It fits with both what does and doesn’t work about the first hour of The Last Dance that we finally hear the leering synths of “Sirius” as the episode wraps up. It works, of course; I have watched too much basketball, and personally gambled too much of my emotional well-being on the NBA during the decade Jordan ruled over the sport with his strange combination of cruelty and grace, for it not to work. The song still sounds like something monumental and monumentally grandiose and maybe a little predictable about to begin, and yet it arrives only as the episode is ending, after The Last Dance lays out its irresistible conceit: an unusually close look at a great and greatly fraught team at the end of an unprecedented run, built around more than 500 hours of never-before-seen footage and made with the participation of all that team’s most important personalities.

But there’s only so much dramatic or narrative tension in play. The team winning its third straight championship and sixth in eight seasons is anything but a “spoiler.” The participation of Jordan, who allowed the cameras access to the team only on the condition that the footage would remain in the NBA’s vaults until he consented to have it released, also lowers the ceiling a bit. Jordan is simply not someone who gets told “no” very often; think of him showing up on set to film a Hanes ad with what can only be described as a Fuhrer-inspired mustache and then consider that the mustache made it into the spots. The simple act of him saying yes to the production guaranteed that it would, to some extent, tell the story that he wanted told as he wanted it told. (The very fact that this series is somehow two hours longer than ESPN’s sprawling eight-part documentary placing O.J. Simpson’s life and trial into a modern history of Los Angeles and American prejudice strikes a perfectly Jordan note of hypercompetitive pettiness.) As an interview subject, too, Jordan isn’t especially insightful or generous: When he revisits the issues with Bulls GM Jerry Krause that were tearing the team apart during the season Phil Jackson dubbed “The Last Dance,” Jordan still seems convincingly aggrieved, but he always sort of seems that way. At least in this hour, the most compelling part of Jordan’s interview segments is watching the wildly fluctuating level of amber liquor in the cut-glass tumbler that sits at his right hand.

Then again, this first hour is mostly about filling in a backstory that is, by now, extremely well known to basketball fans. Director Jason Hehir begins in October 1997, with Jordan and the Bulls gearing up for one last championship run, spins the clock back to Jordan’s rise to greatness at the University of North Carolina and sudden supernova eruption into stardom in Chicago as a rookie in 1984, and then returns to the uneasy apotheosis of the Last Dance season. There is fun stuff studded in there — “I was better than him,” Jordan’s fellow Hall of Famer James Worthy recalls of the one-on-one that Jordan dragooned him into while the two were at UNC, “for about two weeks” — but nothing especially new, and rolling out Literally Barack Obama as a talking head does not do much to spice up familiar material on Jordan’s cultural import or thumbnail diagnoses of Krause’s Napoleon complex or complicated relationship with Jackson. The never-before-seen footage in the first episode, much like the never-before-seen footage in Netflix’s distended documentary series on Aaron Hernandez, does not necessarily cry out for rediscovery, although fans anxious to see Jordan asking late NBA commissioner David Stern, “How’s the wife?” or appearing on a French talk show or being a dick to backup wing Scott Burrell will not be disappointed.

Even if the storytelling in the first episode is mostly rote and baggy, there is also the matter of the footage that has been seen many times before: of Jordan at UNC, in his early NBA career, and at his towering apex. There’s a tension between the highly qualified talking heads describing the singularity of Jordan’s brilliance and the game highlights bearing it out. I watched most of these moments as they happened, at a time in my life when basketball mattered more to me than any other single thing, and yet there is still something startling and implausible about them. Jordan is shockingly fast, then jarringly slow once airborne — he rises and rises above the players thrashing away below him and then just somehow stops and fucking stays there. He seems to find some strange second plateau, or is propelled uncannily forward after seeming to pause. The people around him go up and down, and Jordan is frozen alone at his zenith.

Hehir has a story to tell, and a long time in which to tell it, and he barely begins that work in this episode. An hour is a long time to wait for the pregame fanfare. But where Michael Jordan the basketball player is concerned, I can only second Steph Curry on “Sirius”—it gets me every time.

Want to stream The Last Dance? You can sign up for ESPN+ here. (If you subscribe to a service through our links, Vulture may earn an affiliate commission.)