We’re celebrating the 30th anniversary of The Simpsons episode “Lisa on Ice” at Vulture Festival on November 16-17 in Los Angeles. Cast members Nancy Cartwright and Yeardley Smith, writer Mike Scully, and others will be there — get your tickets here before they sell out!

In May, 2023, I visited the offices of The Simpsons deep inside the Fox Studio Lot in Century City. I was the first reporter in many years to document how the show comes together. More precisely, I was the first reporter in many years to care. After eight seasons, from 1989 to 1997 — what connoisseurs agree is the classic period, the years of “Marge vs. the Monorail” and “Cape Feare” and “Mr. Plow,” from which an endless fount of memes is drawn even today — The Simpsons entered what you might call its Dark Ages. Whereas the classic period was a joke-a-minute spectacle that veered between absurdist physical gags and heartfelt family squabbles, the Dark Ages tried to maintain the joke density but lost the show’s emotional core. The result was an overwhelming blahness and deepening cultural irrelevance just as many shows directly inspired by The Simpsons took off.

That’s all changing. Every person I spoke to for this story — from Broti Gupta, one of the first writers on The Simpsons to have been born after the show’s premiere, to James L. Brooks, one of the series’ founders, to the former members of the No Homers Club fan community, infamous for complaining about the decline of the show — agrees that The Simpsons, in 2023, is undergoing a renaissance. The staff, working in the shadow of a looming writers strike when I visited, are putting out some of the most ambitious, poignant, and funny episodes in the show’s history — episodes that, after all these years, have managed to broaden our understanding of these familiar characters and why they remain so important to so many people. And thanks to the streaming era, a whole new generation is growing up bingeing The Simpsons, bolstering the sense that the show, once left for dead by critics, may really go on forever.

In This Issue

Drew Barrymore Lights Up Daytime

Aficionados know there were some great episodes even in the Dark Ages, the majority of which were helmed by Matt Selman, now The Simpsons’s 51-year-old primary showrunner. Starting in season 23 (2011), he was given two episodes to showrun, then in each season that followed, he was given a few more, so that by season 33 (2021) he was essentially in charge. Al Jean, one of the legendary original writers who returned as showrunner in season 13, is still a showrunner with Selman, but beyond overseeing around four episodes a season, his focus has been on managing the myriad Simpsons brand extensions, be they theme-park attractions or synergistic shorts for Disney+.

Selman, who looks a tiny bit like Krusty managing a Little League softball game on his day off, neurotically demurs anytime I try to give him credit for galvanizing the show. “Everything in showbiz is like, Pretend you do it all. Fuck that. We’re a team. I’m the coach,” he told me. But he made key hires, such as Gupta and Christine Nangle, that gave the staff a younger, more irreverent vibe and a wider array of perspectives. Most important, he gave all the writers license to experiment and not worry so much about what made the show successful in the past. Tim Bailey, a director on the series since 1995, said every episode feels like the “Treehouse of Horror” Halloween special now in terms of its ambition.

The changing of the guard was also important on a structural level. Partisans of the classic period often note that the showrunners in that era departed every two years, regularly infusing the show with new energy and sensibilities. With a little help from the pandemic (“It kind of shook things up,” said Brian Kelley, who has worked on the series for more than 20 years), Selman instituted a model intended in part to replicate turnover at the top: a co-showrunner system in which four of the more senior writers would produce episodes from beginning to end, taking on all the responsibilities that previously would have been left to Selman or Jean. “The pitch was simple: ‘Help me do what we’re already doing, but now you do more of it,’” Selman explained.

Loni Steele Sosthand, a veteran writer but a fairly recent Simpsons hire, said there is an immense sense of authorship over episodes. “Most of us get an episode a year, and we get an opportunity in that episode to really say something — we shouldn’t waste it,” Sosthand explained. Last season, Sosthand wrote an episode around the deaf son of Bleeding Gums Murphy that was based on her deaf brother’s experience. This year, inspired by her own struggles with the idea of racial authenticity as a person of mixed race, she wrote a script in which Carl, a Black character who only recently started being voiced by a Black actor, explored his origins as the adoptee of white parents, having him venture into the Black part of Springfield, which had never been seen before.

The staff have also found a way to look at its main characters with a fresh eye. Homer and Marge, perpetually in their late 30s, are now living in the year 2023, meaning they are millennial parents facing millennial issues. There was a touching episode in 2021 about the psychological ramifications of Marge offhandedly calling Lisa “chunky.” In an episode called “Bartless” from 2023, Homer and Marge fantasize about what their lives would be like if they weren’t Bart’s parents, which ends with them appreciating him for what makes him special, as opposed to wishing he’d meet some “good kid” standard. Beyond exhibiting a different perspective on parenting a “problem” child, the show was reexamining its own relationship to Bart, who was never treated with the same empathy as the other main characters. You feel less like you are watching season 34 than a reboot of season one.

Many of the writers I spoke to made me promise the headline of this article wouldn’t be a variation of “The Simpsons Gets Woke,” because the truth is that the main innovations have been narrative-driven. Over the past two decades, episode run time has been reduced from 24 minutes to 22 or less, a significant drop for a sitcom, demanding tough choices about what makes the cut. Jean crammed the episodes with jokes and bits, giving less airtime to stories. The writers say the show now has fewer gags to make room for character development. Take the season-34 premiere, “Habeas Tortoise,” in which Homer leads a group of conspiracy theorists in the search for a lost turtle. In the past, you’d expect the show to end with a bunch of jokes about how stupid and silly the characters were, but instead it offers a sensitive portrayal of people’s need for community and meaning in the digital age.

Selman sees the show as a “Groundhog Day–type reality, where at the beginning of every episode, they’ve forgotten everything that’s happened before.” That frees the writers from the burden of story continuity, allowing them to push the boundaries of what The Simpsons can do. No recent episode defines the current spirit like “Lisa the Boy Scout,” a mind-bending postmodern intervention into the series. In it, hackers interrupt the episode to play supposed deleted scenes that would “ruin” the audience’s conception of The Simpsons universe. There’s a clip in which Carl learns that his best friend, Lenny, was actually a figment of his imagination and another in which it is revealed that Martin, Bart’s nerdiest classmate, is actually a grizzled 36-year-old father of three with an aging disorder that leaves him looking 10.

It is one of the wildest, all-out funniest episodes in the history of the show, which Carolyn Omine, a seasoned writer, credited to a new process in which everyone pitches “bad” ideas.

The Simpsons is also finding a new audience that doesn’t know the difference between the classic period and the Dark Ages. When Disney first bought 21st Century Fox in 2019, it didn’t totally realize the potential of The Simpsons. When Disney+ launched later that year, it failed to upload episodes of The Simpsons in their original aspect ratio — and its executives were then surprised by how many people cared enough to complain (the error was quickly rectified). Now, Selman speculated to me, The Simpsons might be Mickey Mouse & Co.’s favorite part of that deal. “Even Bob Iger — I don’t know that he watches every episode, but I know that he holds The Simpsons in a special place in his heart,” Selman told me and an excited Yeardley Smith, the voice of Lisa Simpson since 1987. And why wouldn’t he? The Simpsons is once again an extremely popular show.

Parrot Analytics, a firm that uses a range of metrics to determine the popularity of shows in the streaming era, estimates that The Simpsons is the eighth-most in-demand show on television in the U.S., at its peak having seen a 24 percent increase in demand between seasons 32 and 34. Disney informed me that The Simpsons is the fourth-most-watched title on its streaming service in 2023, based on global hours streamed. It is a rare bit of comfort food, a high-episode-count IP that can work on the child-safe Disney+.

I don’t know if you’ve ever spoken to little kids about The Simpsons. I have, and I highly recommend it. Most of them recounted some version of finding the show during the pandemic. Ten-year-old Noemi told me over Zoom that she loved getting COVID because she and her father could watch The Simpsons all day. Noemi’s parents introduced her to the show, but others, like 8-year-old Zane, were led to it by Disney+, where the algorithm recommended this funny-looking yellow-faced family. (Matt Groening, the show’s creator, told me he has no idea how his own 10-year-old found the show.) Their knowledge is encyclopedic: Because every episode is exhaustively listed, all the kids casually threw around official episode titles for which I only had a shorthand when I was growing up. For them, the show is watched on demand in endless quantities. I asked how many episodes they think they’ve seen, and the responses were usually in the 150-to-300 range. And they all intend to watch all 750. Some boys in Noemi’s class already have, and, ugh, it’s so annoying.

The Simpsons also functions as an education in American culture. Noemi’s 8-year-old best friend, Nori, told me about learning of the movie Citizen Kane through the season-five episode “Rosebud.” Her first exposure to one of the most iconic films of all time came through the show’s satirical lens, just as mine did. Other shows make jokes and references at culture’s expense, but The Simpsons, at its best, retells that culture’s stories and weaves them into a common tapestry, a legacy that Selman is keen on maintaining. When Omine told me about a forthcoming “Lemonade parody,” I assumed it was just going to be angry Homer doing Beyoncé in a yellow dress, but instead Homer performed a sort of tone poem about how all he needs is “you three and Maggie” that is equal parts stupid and touching. This is not exactly like what the show would have done in its early seasons — it’s sillier and more emotionally raw — but it reflects the same cultural fluency and willingness to remix touchstone works of art.

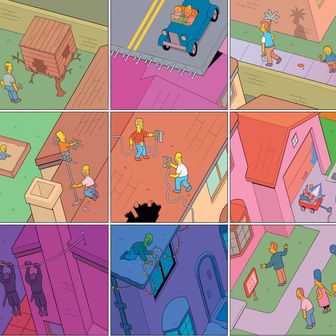

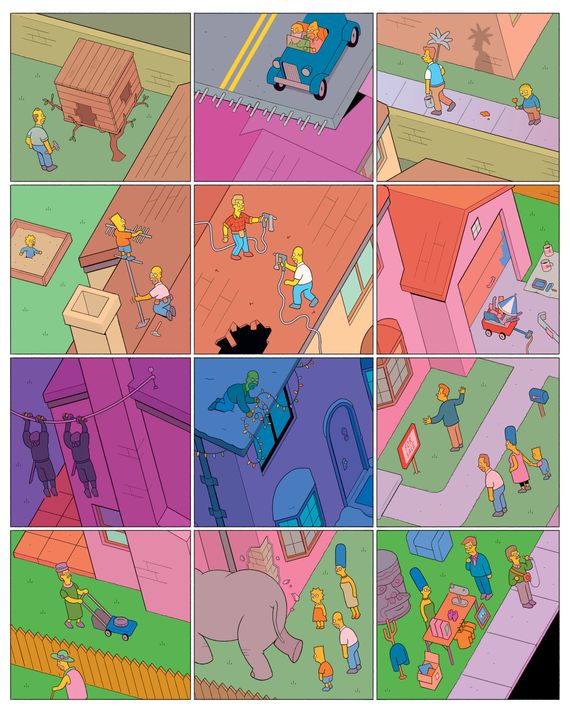

At the end of my second day at the Simpsons offices, Selman brings me into the final edit for the season’s finale. The entirety of the episode follows Homer as he crashes his car and flies through the air in slow motion while trying to process why Marge kept a financial secret from him. This is the sort of avant-garde experimentation that Selman loves. The episode goes in reality- and canon-bending directions (spoiler alert: Homer possibly dies and goes to hell, where he has a conversation with Marge’s father) while still being held up by a relatable story about what is left unspoken between spouses. “Make sure that every episode is poster worthy,” Selman told me, describing the thinking behind the show’s new ambitions. “What is the big exciting visual idea that is unique to that episode that makes it special so you don’t just turn on The Simpsons and say, ‘They’re in the kitchen’ or ‘They’re in the living room’?” Groening said, “Just the idea of Homer flailing through a windshield for several minutes is something that in the olden days, I don’t think we would’ve even dared try.”

To me, the movie The Simpsons is most like isn’t Groundhog Day but Everything Everywhere All at Once. There isn’t one Homer and Marge that resets; there are 750 and counting. Each episode, the core of the characters remains, but the world is slightly different — they have different jobs, different talents, different temperaments. What these past two seasons revealed is that there are still new dimensions of Homer and Marge and new visions of their world worth watching for 22 minutes.

More From This Series

- The Way Devery Jacobs Tells It

- 50 Cent Has Stories to Sell

- In Taylor Sheridan’s America, the Cowboy Is Colonized Too