Spoilers follow for the M. Night Shyamalan film Trap, which opened in theaters on August 2.

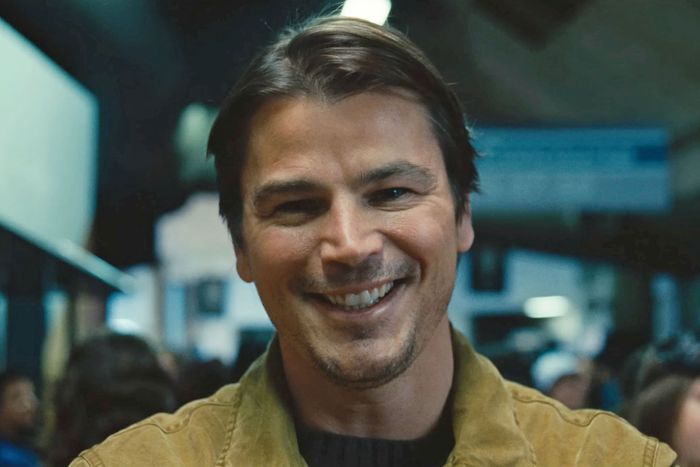

Josh Hartnett has a great smirk. There’s something about that face — narrow eyes, a straight brow, the shock of hair nearly always falling across his forehead — that’s especially well suited to amplifying expressions of amusement and scorn. Hartnett’s serial killer Cooper in Trap isn’t in the business of revealing all of himself, not to his family, not to the cops chasing him, and not to the pop star who stands against him. But every time he smiles at all the effort everyone is going through to capture him, he shows a little more pleasure. All this, for me? Cooper lives for this duplicity, and that smirk is his truest declaration.

Hartnett’s working-class suburban dad looks like a blandly handsome everyman attending a concert with his 12-year-old daughter, Riley (Ariel Donoghue), and then — bam! His mind is elsewhere as he figures out how to outsmart the cops. He gives everyone he encounters just enough attention to feel seen, but not so much attention that they become curious about him. Hartnett’s ability to switch between personalities is what fuels Trap’s relentless tension, and the fluidity of his performance means you never know exactly what to expect from either Cooper or his serial-killer persona, “the Butcher.” Hartnett and Trap writer-director M. Night Shyamalan both seem to recognize that despite the actor’s teen-heartthrob beginnings, part of the his appeal has always been a glimmer of darkness. Those brown eyes can slide very easily from warm and puppy doggish to threatening and smug, and Trap is an exhilarating watch because it allows Hartnett to go full freak.

Sure, Hartnett’s played good guys (in 30 Days of Night, he was a sheriff defending his Alaskan town against a vampire invasion); rom-com leads (his performance in 40 Days and 40 Nights is a millennial gay root, as documented by my brilliant colleague Rachel Handler); and outsiders enduring ludicrous circumstances, like aliens infiltrating a high school in the very fun cult classic The Faculty. He does perfectly fine in those roles; he’s a serviceable leading man. But when a character allows him to put that whispery voice and that gangly frame to sly, scheming, deceitful effect — to play someone who’s already been disappointed by the world and is willing to spread that misfortune around so they’re not so lonely — that’s when Hartnett really clicks.

Some of this could be seen in Penny Dreadful, in which Hartnett played a charming, reckless, older-than-his years marksman and secret werewolf who hooked up once with Dorian Gray. (You will not regret consuming this gonzo series.) Some of the most compelling performances of Hartnett’s career, though, dip more fully into villainy. He was the school hottie who broke Lux Lisbon’s heart in The Virgin Suicides; the guy who spread lies and gossip to poison his best friend’s relationship with his “horny snake” girlfriend in O; the suave assassin the Salesman in Sin City, who sweet-talks his targets before killing them; an all-American-hero astronaut who murders his colleague’s wife and her son when she won’t give in to his advances in the Black Mirror episode “Beyond the Sea.” Many of these roles rely on his ability to seduce people, to get close and secure their trust before betraying them, giving his magnetism a sharply sinister edge.

But Trap gives Hartnett his most comprehensive and multifaceted villain showcase yet, and he uses his whole body for it. He looms, he slows his speech, he stares. He never explodes, but he simmers; he’s composed and deliberate, conveying someone who always has the next step of his plan figured out, and he’s just waiting to get there.

Cooper performs multiple versions of himself throughout the film, each suited to whatever situation he’s in. Once Shyamalan starts splitting Hartnett’s face vertically, shoving him to the edge of the frame and dividing him down the middle, those myriad Coopers take more distinctive shape. We see the supportive dad, hugging Riley and smiling at her opportunity to be onstage with her favorite pop star, Lady Raven (Saleka Shyamalan), only minutes after he lied and said she has cancer to secure that meet and greet. The methodical, dead-eyed problem solver striding through the arena, testing doors and scoping out cameras. The affable, apologizing-for-himself arena employee, confidently making his way through a crowd of cops. The service-minded firefighter, so attractive in his familial devotion that he catches the eye of a flirtatious rapper walking by. The serial killer, dropping his aw-shucks persona to strong-arm Lady Raven into giving him an escape route, practically sneering at her fear. Hartnett crafts each of these Coopers with specific choices: He pitches his voice higher when Cooper talks to Riley, he blinks back tears when pretending to be an overwhelmed concessions worker, he scoffs openly at Lady Raven’s attempts to outsmart him once she’s bluffed her way into his home.

Along the way, Shyamalan supports Hartnett with compositions that focus on some element of his body or face and then push in, magnifying every choice. The film’s final sequence, in which a handcuffed Cooper is being driven to jail, might be the film’s standout display of the character’s layers. In the minutes before, it seemed like Cooper had accepted his fate; Hartnett plays him subdued, even remorseful, his shoulders down and his head hung low as he leans over his daughter’s fallen-over bike, picks it up, and rights it on their front lawn before he’s loaded into a transpo van. Here is a man thinking about the past and the future, all he’s done and all he’s lost. But once Cooper is inside the locked box, a tire spoke emerges from Cooper’s sleeve. Shyamalan stays on Hartnett’s face as he works it on the handcuffs, striving and trying and then, finally, when we hear the click of the handcuffs opening, exalting. He chuckles at how easy this was. When he uses his now-separated hands to smooth his hair back and rearrange his face into a look of readiness, this is Cooper resetting himself, and Hartnett finding another aspect of the character to play. In trying to cage Cooper in, Trap frees Hartnett to be the baddie he’s always been.

More on 'Trap'

- I’m In the Tank for M. Night Shyamalan

- Signs Is the M. Night Shyamalan Experience at Its Best

- Trap Ends Right As It Gets Interesting