What was the home front during WW1?

While the battles of World War One were fought overseas, the whole population of the UK was affected by the war.

Many of those who remained 'at home' worked in industries to support the country and its armed forces. Some people faced the danger of German bombing raids. And by the end of the war, everyone in the country was subject to food rationing.

The hardships and efforts of ordinary British people led to everyday life being referred to as the home front

Find out more about the home front during World War One.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYDefence of the Realm Act (DORA), 1914

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYOn the 8th August 1914, within days of entering World War One, the UK Government passed the Defence of the Realm Act.

The Act was designed to ensure the smooth running of the war effort. It provided legal means to:

- protect ports and military bases from sabotageTo deliberately damage or destroy something so that it cannot be used.

- ensure that vital resources such as coal, iron and food were carefully monitored to prevent shortages

- take direct control of factories to ensure that they helped with the war effort

- prevent spying by ensuring that all non-British citizens were registered with the police

- ban acts such as taking pictures of military bases and purchasing binoculars without a licence

Just as importantly, the Act allowed the government the ability to control and censor essential communications such as newspapers and radio.

While this would prevent the enemy from finding out the British war plan, it also meant that the population at home would not know the full facts about the war. Bad news was often suppressTo prevent information from being spread. so that it did not damage public morale.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYHow did WW1 affect daily life?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYDORA had an impact on the everyday lives of normal citizens.

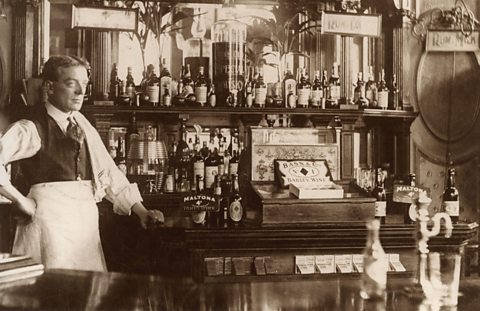

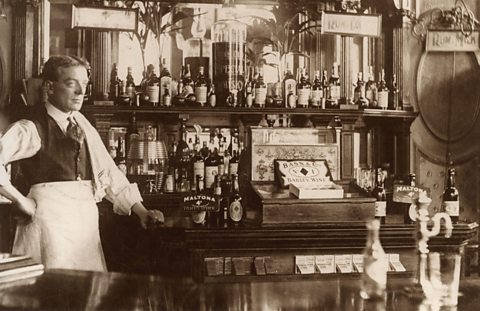

Pubs came under new legislation to stop workers from getting too drunk, as this could affect their ability to do their jobs.

- pubs could only open for five and a half hours each day and had to close by 9pm

- they were not allowed to open on a Sunday

- beer was watered down in order to weaken it

- individuals were forbidden from buying rounds of drink for them and their friends.

There were other, sometimes strange, laws:

- in an attempt to conserve food, the public were no longer allowed to feed ducks

- flying kites and lighting bonfires were banned to reduce the chances of messages being passed to the enemy

- churches were not allowed to ring their bells – this was to reduce their chances of being targeted during any air raids

DORA was introduced to protect those who remained on the home front but some people resented the restrictions. They argued that they were destroying freedoms that the population had become accustomed to.

However many saw the new restrictions as necessary to win the war and followed them for the duration of the war.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWhat was working life like during World War One?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe Defence of the Realm Act had a big effect on industries that were seen as crucial to the war effort. This affected the working lives of thousands of Britons.

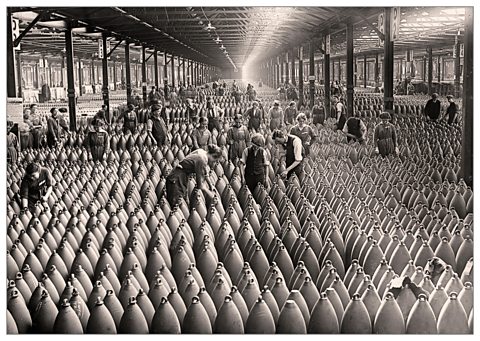

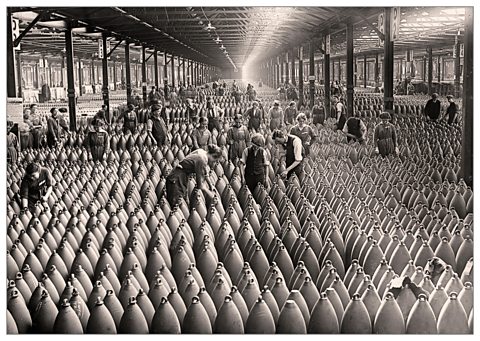

The Munitions of War Act 1915 was passed on 2nd July 1915. The government imposed the act to boost production of ammunition as there was a severe shortage of shells for the army’s heavy guns.

The act imposed strict measures on working conditions, and wages for all people who worked in the factories that made ammunition.

It also made strikes illegal and also banned munitions workers from leaving their jobs.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWhy were there strikes and protests during World War One?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe restrictions imposed by the Munitions Act were met by protest. Some of the biggest occurred in Scotland.

In Glasgow, the Clyde Workers Committee was established in 1915 to campaign against the Munitions Act.

The Committee organised and supported strikes to demand higher wages for workers in key industries.

The Committee also campaigned against high property rents in the city. Rent strikes in Glasgow were mostly organised by female activists such as Mary Barbour.

The Committee backed these strikes and, eventually, the government acted to freeze rents.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWhy were strikers arrested during World War One?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe government feared that the strikes would disrupt the war effort.

As a result, several of the organisers of the Clyde Workers Committee were arrested under the laws brought in by the Defence of the Realm Act.

Newspapers who criticised the war or encouraged industrial action were also shut down and the editors, such as John Muir, were arrested.

Other activists were arrested, too. Many, such as the trade union leader, Willie Gallacher, and the teacher and lecturer, John Maclean, described themselves as either SocialismSocialism is a social and economic belief that there should be public rather than private ownership property, industry, and natural resources. or communist.

The level of left wing socialist protest in the city led to Glasgow earning the nickname Red Clydeside.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYHow did Scotland's industry contribute during World War One?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYLong before World War One, Scotland had a very well-developed industrial and manufacturing sector.

Scotland's Central Belt had coal fields, providing fuel in other factories to create things such as iron and steel.

Iron and steel were used to make other things such as ships and trains.

When World War One broke out, Scotland's industries were put to work helping the war effort.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYScottish shipbuilding during WW1

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYShipbuilding was the main wartime contribution of industry along the River Clyde.

In 1911, around 54,000 people in Lanark, Renfrew and Dumbartonshire were employed in shipbuilding.

Firms operating on the Clyde produced vessels of varying size, such as cargo steamers, oil-tankers, and a new, large class of warships called dreadnoughts.

In 1913, Clyde shipyards built 353 vessels. This was equal to that of the whole ship output of Germany, and greater than any other single British shipbuilding centre.

In fact, Clyde shipyards made up around 90% of the shipbuilding activity in Scotland.

On the outbreak of World War One, all shipbuilding activity was directed to support the war effort. Clyde shipbuilders were essential for the British war effort. In total, 481 warships were built on the Clyde between 1914 and 1918. (Source: Go Industrial)

The wartime boom in business brought a huge amount of money - the three leading yards won orders worth over £16 million. However the boom did not last and, after the war ended, production on the Clyde went down by two thirds.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe Scottish steel industry during WW1

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWorld War One created an enormous increase in demand for the production of iron and steel for Scottish heavy industry.

Several Scottish steelmakers were approached by the Ministry of Munitions to carry out work for the government, such as William Beardmore and Company on Clydeside, and David Colville and Sons, based in Motherwell.

Steel output doubled during the war. Tanks and battleships needed thick steel armour plating for protection. Around ninety percent of this armour plate came from Glasgow.

During the years 1914-1918, David Colville and Sons produced 631,000 tons of shell bars (to be turned into shells), with over 2,000 people employed at their Clydebridge factory alone. Beardmore's Parkhead Forge employed more than 20,000 people at its peak during the war.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYScotland's jute industry during World War One

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYDundee’s jute industry benefitted greatly from the war.

Jute was a tough natural fibre that could be used to make strong, hard-wearing fabrics.

During World War One, jute was used to make sandbags to fortify trench defence, and rucksacks to hold soldiers belongings and military supplies.

As a result orders often topped six million sacks per month with the jute trade employing thousands of people in Dundee (25% of male workers and 67% of female workers).

As with some other industries, the jute industry went into a rapid decline after the war ended.

Image source, ALAMY

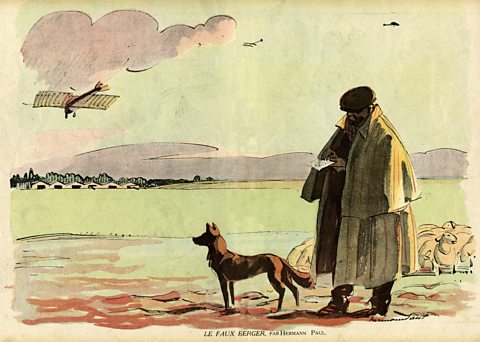

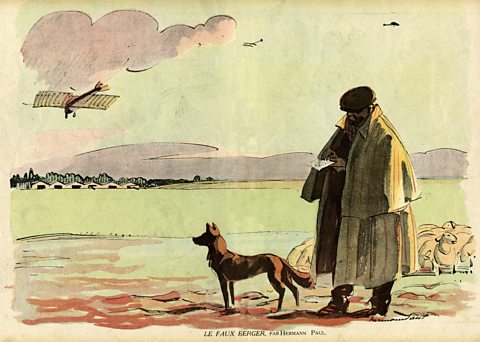

Image source, ALAMYScotland's agriculture and farming during World War One

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYHuge numbers of farmers and farm labourers signed up to fight in the war. As a result farm workers were able to demand higher wages. Women, boys, older men and even prisoners of war and conscientious objectors helped replace the men who had joined the army.

Demand for food and other products increased during the war. Imports of lamb and other meat were affected by U-boat attacks, so demand for Scottish lamb increased. By 1918, sheep prices were 60% higher than they had been in 1914.

Alongside this, as the number of men joining the army rose, so did the number of uniforms required to clothe them. Again, Scottish sheep farmers profited from this as, in 1917, the British Government purchased all of the wool in Scotland.

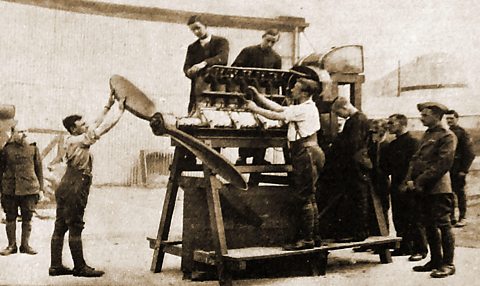

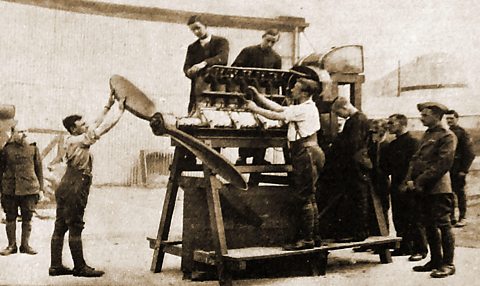

The war led to the mechanisation of farming in Scotland and the introduction of machines to complete what were once manual labour jobs.

During the war, this meant that farms were able to keep up with demand with fewer labourers. However, when the war ended and those who volunteered returned, they found that there were no jobs for them, leaving many unemployed.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYRationing during WW1

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMY Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYBritain relied on international trade with the Empire and other nations to feed the people. There was no expectation for the country to be self-sufficient and provide enough food for the entire population indefinitely.

When war broke out, Scotland only had enough food supplies to sustain the country for three weeks.

At the beginning of the war Britain believed that there would be minimal disruption to its food supplies. However as the war continued, some foods became difficult to get hold of.

Lots of food was sent away to feed soldiers fighting in the war. There was less food arriving, as ships carrying supplies were attacked by German U-boats.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYFood prices during WW1

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn 1917, the British Government were forced to introduce voluntary rationing to try and keep food prices down.

However, by March 1917, this policy had failed and food prices rose dramatically.

- potatoes more than doubled in price

- cheese and eggs were 45% more expensive compared to 1914

- meat, bacon, and butter prices rose by 30%-35%

- flour, milk, and sugar prices rose by 20%-25%

- bread, margarine, and fish prices increased by 13%-18%

- the price of tea rose by 7%

It soon became clear that those with money were able to afford these price rises however working class families began to struggle.

In order to rectify this, full scale RationingRationing was a policy that restricted the availability of goods such as food and fabrics when supplies of them were low. was introduced in April 1918. It was not ended in its entirety until 1920.

The high prices were limited using price controls (items were not to be sold beyond a certain price) set by the government and most foods were rationed.

Alongside these measures, Britain also introduced a convoy system to protect food shipments arriving from America.

Lots of merchant ships carrying essential food and resources were banded together and protected by battleships to protect them from the U-boats.

This drastically reduced the number of ships sunk and allowed for food to arrive from across the Atlantic.

By introducing these measures, the Government ensured that food was once again affordable and that everyone, no matter rich or poor, had equal access to a basic amount of food to survive.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYGerman bombing raids during WW1

The country's experience of war was not limited to the soldiers fighting overseas.

16th December 1914 saw the German Navy bombarding the towns of Scarborough, Whitby and Hartlepool on the north east coast of England. 137 people were killed in the attack.

The deaths of British civilians caused outrage, and "Remember Scarborough" became a slogan used to encourage men to enlist in the armed forces.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWorld War One saw the creation of the new military tactic of airborne warfare.

On Christmas Eve 1914, a single German plane flew to Dover and dropped the first aerial bomb ever to land on British soil. exploded in a garden. Only one person was injured - a man knocked from a ladder by the explosion.

At the time planes did not have enough fuel to travel significant distances to take part in air raids. And they did not have an effective method of dropping bombs. The bomb that fell on Dover had been dropped by hand over the side of the plane.

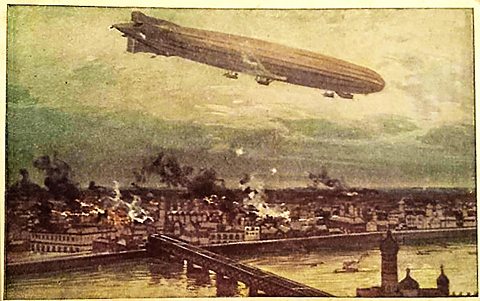

WW1 Zeppelin airship raids

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMY Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYSoon after this raid, the Germans adopted the use of airships called Zeppelins as the principal means of bombing Britain. The first raid was on Great Yarmouth and King’s Lynn in January 1915

Zeppelins were lighter-than-air vessels as they were filled with hydrogen and floated – much like a balloon.

Although they were powered by propeller engines, they relied on good weather in order to make it to their targets.

If the weather was poor then they could be blown off course and their bombs dropped miles off target. In March 1916, a raid was planned for Rosyth in Scotland, however Liverpool was hit instead!

A second raid on the 2nd and 3rd of April 1916 targeted the naval base at Rosyth and the Forth Bridge. Unable to find their targets, the two airships dropped their bombs on Leith and Edinburgh, and Newcastle instead.

13 people were killed in the raid, and 24 people injured.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWatch and listen to one boy’s account of a London air raid in 1916 during World War One.

NARRATOR: On the night of 2 September 1916, German airships attacked London.

Williams Leefe Robinson, a young lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps, took to the air in his single engine biplane to defend the city.

On the ground a young boy, Patrick Blundstone, watched the night’s events unfold.

Afterwards he wrote a letter to his father describing what happened.

PATRICK BLUNDSTONE: Dear Daddy, I hope you’re not alarmed.

You shouldn’t be, unless you know where one of the Zepps went.

I had heard that it raided London, up The Strand, and caused heavy causalities.

This I know because I saw, and so did everyone else in the house.

Here is my story…

I heard the clock strike 11 o’clock. I was in bed and just going to sleep.

Between 2 o’clock and 2.30 o’clock, we saw flashes and then heard bangs and pops.

Suddenly a bright yellow light appeared and died down again.

“Oh! It’s alright,” said the Poolman. “It’s only a star shell.”

That light appeared again. We rushed to the window and looked out and there right above us was the Zepp!

It had broken in half and was in flames, roaring and crackling.

It went slightly to the right and crashed down into a field.

It was about a hundred yards away from the house and directly opposite us.

It nearly burnt itself out but it was finished by the fire brigade.

I would rather not describe the condition of the crew, of course. They were dead. Burnt to death.

The Zepp was bombed from an aeroplane above with an incendiary bomb, by a Lieutenant Leefe Robinson.

We have some relics, some wire and wood framework.

The weather is beastly. I hope you’re all well.

Your loving son, Patrick.

P.S. Please don’t be alarmed, all is well that ends well, as this did for us. We are all quite safe.

NARRATOR: The burning airship lit up the sky for miles around.

Thousands of people watched as the wreckage plummeted into a field, in the village of Cuffley.

It was the first time a Zeppelin had been shot down in Britain.

The next morning 10,000 people gathered at the crash site to collect a souvenir.

The day became known as Zepp Sunday.

The pilot who shot down the airship became an overnight hero.

Two days later, William Leefe Robinson was awarded the Victory Cross, the highest award for gallantry.

The raids over Britain continued throughout 1917, with German Gotha planes supporting the Zeppelins.

Zeppelins made 51 bombing raids on Britain during the war:

- 557 people were killed

- 1,358 injured

Aeroplanes carried out 52 raids:

- 857 people were killed

- 2,058 injured

To counter this aerial threat, the Royal Flying Corps was established and many British pilots flew in terrifying night missions to protect the British people from the impending bombs. The Royal Flying Corps would later become the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The final Zeppelin raid against Britain was in August 1918, three months before the war ended. The mission failed with the five Zeppelins involved attacked by planes from the Royal Flying Corps…

Test your knowledge

More on World War One

Find out more by working through a topic

- count8 of 9

- count9 of 9

- count1 of 9