Introduction: railways

The arrival of the railways revolutionised life in Britain. The growing rail network opened up the possibility of fast travel across the whole nation and it provided an efficient way of transporting the goods and resources that powered the Industrial Revolution.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYBefore the railways

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYBefore railways were introduced, travel and transport in the UK was difficult.

Most roads were badly maintained. They had poor surfaces and many were little more than tracks. Roads could flood and often became unusable in bad weather.

People relied on horses, or horses and carts to travel any distance. This was slow and the size of load that could be carried was limited.

New factories and industries needed to transport raw materials, coal for fuel, and finished goods. These materials usually had to be transported in amounts that horses and carts would struggled to move.

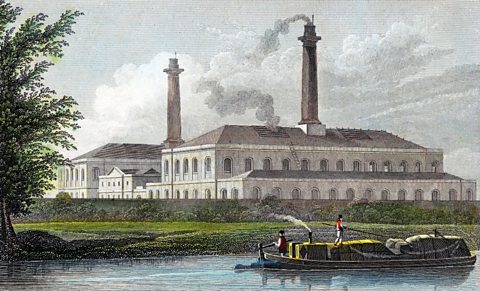

Industries located on rivers could use boats for transport. But this limited where businesses could trade. At the start of the Industrial Revolution, canals and barges provided the solution.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYCanals in the Industrial Revolution

Image source, ALAMY

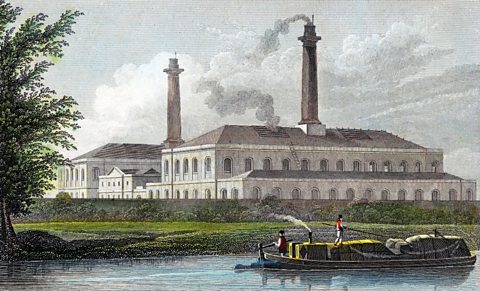

Image source, ALAMYThe canals were created to transport large quantities of heavy goods, safely and cheaply.

The most extensive canal network can be seen in the Midlands of England where there were numerous coal fields.

For example, Josiah Wedgwood used the canal network to transport his pottery goods from the factory in Stoke-on-Trent to new mass markets all over Britain.

The benefits of canals was that they could carry large amounts of goods over long distances compared to horse and cart.

While they made moving huge amounts of coal cheaper and easier, the canals were very expensive to build.

The Bridgewater Canal that runs through the north west of England was opened in 1761 to allow coal to be transported to Manchester. Ultimately, the forty-one miles of canal cost the equivalent of £28 million. Source: Stories of Inventors and Discoverers in Science and the Useful Arts: A Book for Old and Young, Timbs, J, 1860

Another drawback of canals was that they were slow – they could only move at the walking speed of the horse that pulled them.

Hilly terrain also caused problems as barges found it difficult to navigate stretches of water that featured a change in height.

Canals could also be very seasonal. In winter, a bad cold spell could mean that the canals froze over.

To cross hills, barges had to navigate a system of canal locks that raised or lowered the water levels of the canals.

For example, Neptune’s Staircase near Fort William is a series of eight locks that raises the Caledonian Canal by 19 metres. This all adds to transport time.

Image source, ALAMY

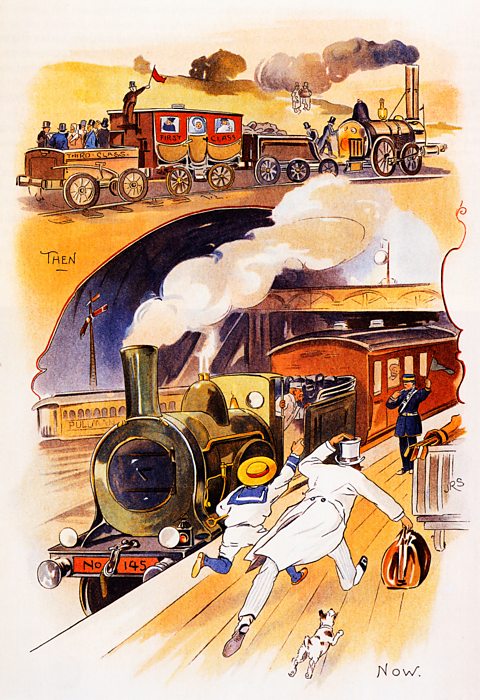

Image source, ALAMYThe age of rail during the Industrial Revolution

Early railways

Image source, ALAMY

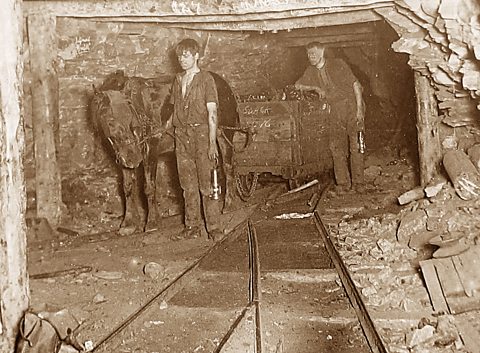

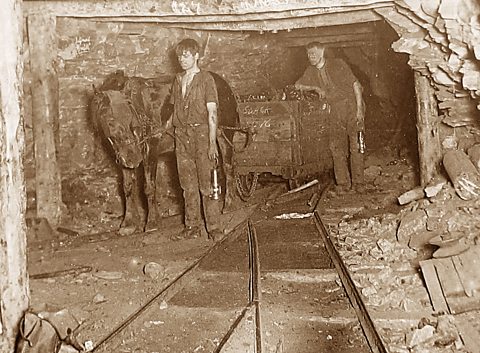

Image source, ALAMYThe earliest railways were built at collieries to help move the coal extracted from the mines to where it could be transported by canal, river or sea.

These railways did not use trains but horses to pull wagons loaded with coal and only covered short distances near the mines.

Later, these railways were extended greater distances to transport coal to where it was needed in the factories and foundries.

The oldest of these railways was the Middleton Railway in Leeds, England. Built in 1758, it is the world's oldest working railway in continuous usage.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYSteam powered locomotives

Image source, ALAMY

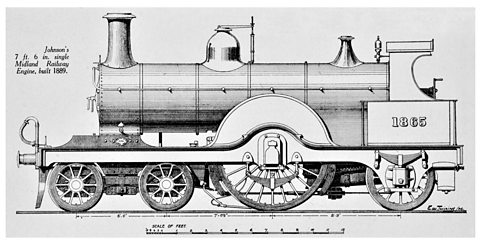

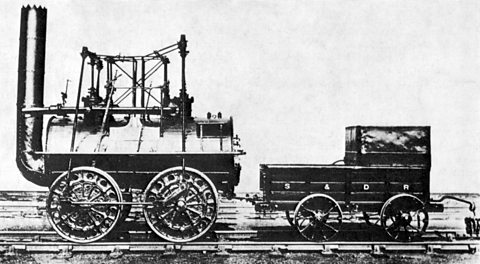

Image source, ALAMYThe first commercial usage of steam engines to pull goods on railways rather than horses was at the Middleton Railway in 1812.

Steam engines and steam-powered train travel began not long after. These railways were expensive to build and operate and so, to bring in more money, they were opened to the public as a new means of travel.

The engineer and inventor, George Stephenson, known as the ‘father of railways’, had worked building steam locomotives for coal mines.

In 1825, he opened the first locomotive route from Stockton to Darlington. This led to ‘railway mania’ throughout the 1830s and 1840s and the rapid growth of the railways.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYScotland's first railway

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe first public railway in Scotland - and the first to use steam locomotives in Scotland - was the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway which opened in 1826.

The railway was built to link a colliery at Monklands, Strathclyde to the Forth and Clyde Canal at Kirkintilloch, East Dunbartonshire.

The line supplied coal to the homes and industries of Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Later on, the railway carried passengers and became a key part of the passenger rail link between Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYHow the navvies built the railways

In this video, learn about the navvies and the impact of railways in Britain during the Industrial Revolution.

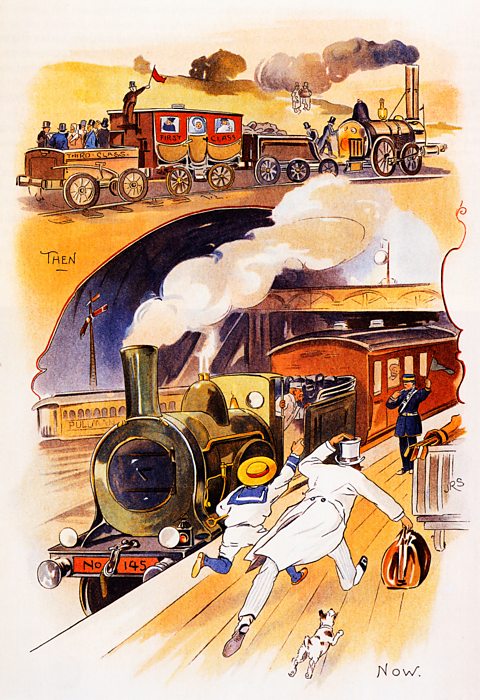

A journey from Glasgow to London. Way back in the 1700s, that’s a ten day ordeal, but the railways would reduce that ten days to a mere ten hours – and it was all thanks to the navvies.

Incredible engineering was achieved with little more than shovels, picks and gunpowder. A navvy would awaken in a squalid, disease-infested temporary shanty town and embark on long, brutal days building tracks and tunnels. For every mile of railway made, three workers would die.

But despite the mix of people – Irish immigrants, relocated Highland Scots, and more – there was a sense of comradeship; shared identities and cultures, and even their own language. Really, the navvies, well, transformed the UK.

Now, the navvies first got their name from the navigational canals they dug, like the Monklands Canal, built to transport loads of heavy coal from mines to factories, powering the Industrial Revolution. Effective, but slow.

The invention of the steam train and railways offered a way of transporting loads of coal really quickly. The Monklands Canal was replaced by the speedier Garnkirk and Glasgow railway. This was a huge success, and, soon enough, the rest of society saw the benefits of the railways.

As cities grew at an incredible rate, railways sprung up around the UK, keeping pace with the rampant demand for food, goods, and coal which was used to make steel.

Britain transformed, lines stretched as far as Penzance in Cornwall and Thurso in the Highlands, and cities connected by rail grew at a wild pace, particularly those involved in the rail industry itself, like Glasgow, which built twenty-five percent of the world’s steam locomotives, and ship them off to emerging rail systems across the world.

By 1900, nearly five percent of the UK’s population worked for railway companies. As the railways developed, so too society. Fresh food could be transported, and communication improved with post delivered three times a day, and telegraph wires built alongside railways.

But most dramatic was the effect it had on workers and families across the UK. The 1844 Railway Act required companies to sell cheap tickets, allowing working class people to travel across the country, finding work in different region, and mixing with people from all different backgrounds.

Quick transport meant national newspapers could be distributed. Spectator sports like football became nationwide – fans could travel far and wide to support their teams. And standard time – railway time – came in as a result, since a station in Bristol had to run to the same timetable as one in London. Railways made holidays possible, with coastal resorts in easy reach of workers from the cities.

So, the next time you sit relaxing on a train for a day at the beach, spare a thought for the navvies who made it possible.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn 1830, there were only 125 miles of railway lines in Britain.

Forty years later, there was 13,000 miles. (Source: Cobb, M, The Railways of Great Britain, 2003.)

This incredible expansion of the railway network was only made possibly by a large labour force that laid the rail lines, dug cuttings and tunnels, and built the embankments, stations, bridges, and viaducts that the new rail system would need.

All this was carried out by workers known as navvies.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWho were the navvies?

Navvies was a name given to the men who built the miles of railway lines across Britain. Navvie is short for navigator.

The navvies were originally paid to dig out the routes for the canal system.

After 1830, many were employed to do the hard work of laying the rails and building the embankments for the railways.

At the peak of the railway boom there were around 250,000 navvies. About a third of them came from Ireland to find employment. (Source: The Railway Archive).

The navvies worked long hours lived in camps alongside the railways as they built them. Often their wives and children would accompany them.

The wages could be good but the work was dangerous and exhausting. The work was carried out using simple tools such as pickaxes and shovels.

Living and working conditions were poor and not very safe. Thousands died in accidents at rate of around 500 men a year during the 1880s and 1890s. Source: The Railway Museum: Navvies: Workers who built the railways

Impact of the railways in Britain during the Industrial Revolution

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe use of trains to move huge amounts of raw materials, fuel, and finished goods quickly around the country underpinned the Industrial Revolution.

Beyond this, there were also many positive impacts of the railways on British people.

The railways became a major employer. From train drivers, to engineers, through to ticket office staff and train conductors, the rail companies employed thousands of people.

The rail network allowed people to move to other areas to live and find work.

People’s health improved as regular trains provided better access to fresher and cheaper food.

The use of trains by Royal Mail meant people could stay in touch easily. It also allowed newspapers to sell to a national readership much more easily.

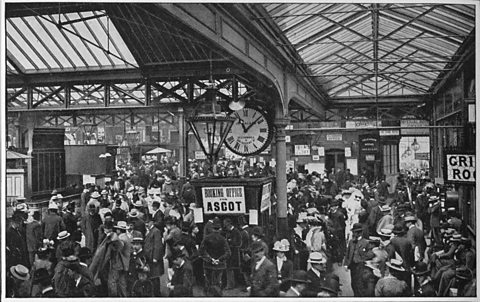

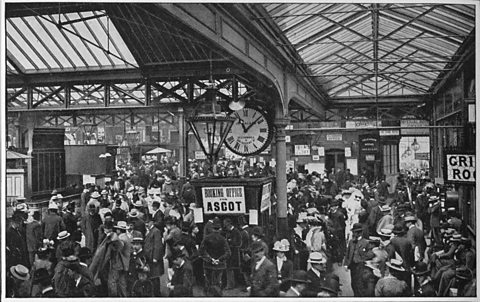

Trains boosted tourism and allowed people to travel to different parts of the country. It gave many city-dwellers access to the fresh air of the countryside.

Glaswegians would escape the city in the summer to go to seaside resorts such as Largs, Rothesay, and Lamlash on the Isle of Arran. The rail lines also made the Highlands more accessible to visit.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYRailway time

The railways also helped to introduce standardised time across the British Isles.

Before the railways, clocks in different areas could be set to different times - a clock at a train station in London might read 2pm while, at the same time, a clock in an Edinburgh station might read 2.10pm.

The railway companies introduced standardised time so that train timetables could be coordinated so that trains departed and arrived on time.

The railways and sport

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYEven sport benefitted from the railways.

Soon most towns had football and rugby teams. The trains allowed sports fans who lived outside of these towns to travel to support their team.

Affordable train travel even led to a new phenomenon - fans travelling to other towns to support their club.

Some railway companies were keen to capitalise on these new travellers and introduced cheap train tickets for football supporters. Source: Science and Industry Museum: Football, trains and the rise of the travelling fan

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYTest your knowledge

More on Industrial Revolution

Find out more by working through a topic