Key points

- Elizabeth I was a Tudor monarch who ruled England from 1558 - 1603.

- Despite her long reign, Elizabeth was never expected to become queen. She was last in line to the throne of all of Henry VIII’s legitimateA term used during the Tudor period to describe a person who had been born to married parents. By contrast, someone with unmarried parents was considered to be illegitimate. children.

- After the execution of her mother, Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth’s early life was full of danger, which helped shape the queen she became.

- England experienced a great deal of change during Elizabeth’s reign. Religion, society, the arts, trade and exploration were all very different by the time of her death.

Activity - who are you at the court of Elizabeth I?

Elizabeth's family

Elizabeth I was born Princess Elizabeth in September 1533, the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife.

One of the reasons for Henry’s break from Rome was that he wanted to marry Elizabeth’s mother. He created the Church of England, with himself as its head, removing power from the in Rome.

Henry had wanted a male heirA person who inherits a title or property when its owner dies. to the throne, but he and Anne only had Elizabeth. In 1536, Anne was executed on charges of treason, and within days Henry had married Jane Seymour. She would be one of four stepmothers to Elizabeth.

Elizabeth had two legitimateA term used during the Tudor period to describe a person who had been born to married parents. By contrast, someone with unmarried parents was considered to be illegitimate. half-siblings, Mary, born in 1516 to Henry and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and Edward, born in 1537 to Jane Seymour, Henry’s third wife. When Henry died in January 1547, Elizabeth was third in line to the throne.

Who was the young Elizabeth I?

Elizabeth was only two and a half years old when her mother was executed. Following the death of her mother, Henry declared Elizabeth to be illegitimate. Around a year after Anne’s execution, it was reported that Elizabeth asked why she was now being called ‘Lady Elizabeth’, rather than ‘Lady Princess’.

Despite her mother’s fate, Elizabeth looked up to her father. When she became queen, she would often proudly make reference to her likeness to Henry. She had his red hair and strong personality. Elizabeth even called herself the ‘Lion’s cub’. She wept uncontrollably when Henry died.

Like all royal children, Elizabeth spent her early years away from courtA name given to the residence of the monarch, their servants and politicians. The court regularly moved between different palaces., in palaces such as Hatfield House. Her education and development were overseen by a governess, Katherine Ashley, who would become her lifelong companion.

Elizabeth was highly educated. By the age of 14, she could speak fluent French, Italian, Welsh, Spanish, Latin and some Greek. She was tutored by Protestantism A form of Christianity that originated in the early 16th century, after a German priest, Martin Luther, published a long list of criticisms of the Catholic Church. men such as Roger Ascham, who taught at the University of Cambridge. She was described as a conscientious and talented student.

Elizabeth's journey to becoming queen

Elizabeth was 13 years old when Henry died and her brother, Edward, became king. The death of her father marked the beginning of a period of instability in Elizabeth’s life.

Elizabeth had become close to her last stepmother, Catherine Parr. Elizabeth went to live with Catherine and her new husband, Thomas Seymour.

Thomas Seymour was dangerously ambitious. He plotted to make Elizabeth his next wife if Catherine died. Edward’s government had Elizabeth and members of her household interrogated. It was believed that Seymour had plotted to marry Elizabeth so that he could then seize the throne from Edward, and make himself king with Elizabeth as his queen. Elizabeth could have been executed if she had been found to have encouraged Seymour. She protested her innocence and survived, but Thomas Seymour was executed.

When Edward died at the age of 15, Elizabeth’s older half-sister, Mary, seized the throne from Edward’s choice of successor, Lady Jane Grey. Again, Elizabeth faced danger. Mary was CatholicA member of the Catholic Church. Catholics believe in having a hierarchy of priests and bishops beneath the Pope, who is the Head of the Church. Members of the Catholic Church also believe in devotion to the saints and the Virgin Mary, Jesus' mother, and in holding Mass. , and while many modern historians believe that the majority of people in England were happy with the return to Catholicism, some Protestants did not accept it. When Mary announced that she was to marry King Philip II of Spain, who was Catholic, there was a Protestant uprising against Mary. This was led by a man called Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger, whose father had been accused of committing adultery with Anne Boleyn.

This was dangerous for Elizabeth because it was rumoured that that the men led by Wyatt sought to place her on the throne as a Protestant queen. Again, Elizabeth found herself interrogated and spent two months in the Tower of London, fearful of being executed. She spent the next four years of her life as a prisoner, under house arrest.

In November 1558, Elizabeth learned about the death of Mary I, and that she would inherit the throne. Elizabeth believed it was a miracle and exclaimed, “this is the Lord’s doing, and it is wondrous in our eyes.”

What issues did Elizabeth face?

Elizabeth inherited a kingdom with a range of issues for her to deal with. The main questions she would need to find solutions to were:

- Who would help her rule?

Elizabeth inherited a government filled with powerful Catholics selected by her sister, Mary. Elizabeth was a Protestant.

- How could she deal with England’s debts?

Elizabeth’s father, Henry, brother Edward and sister Mary had caused England to fall further into debt during their reigns. Elizabeth would need to find a way to pay these debts off, and also begin to raise funds.

- What religion would she want for England?

It was accepted that the faith of the monarch would become the religion of the kingdom. Yet Elizabeth was a moderate Protestant, and her sister had restored Catholicism to England. How could Elizabeth change the faith of England again and avoid opposition?

- How could she prove she was the rightful queen?

Her father had called her illegitimateA child born to parents who are not legally married to one another. after the death of her mother, although he later passed an act restoring her to the line of succession. Her mother had also been very unpopular. Elizabeth would need to prove that she was a true Tudor monarch.

- Who would she marry, if anyone at all?

In Tudor times, it was relatively unusual for a woman to remain unmarried, and there were useful alliances to be made in marriage. Yet if Elizabeth married the wrong man, he might try to seize power or start a rebellion. What could she do?

Government under Elizabeth I

England had endured a period of instability. People had suffered economic hardship, outbreaks of disease, rebellion and poor harvests. The kingdom was also in debt. Elizabeth would have to deal with these issues and decide what to do about her government, which was mainly populated by Mary’s chosen Catholics.

Elizabeth’s early life had made her careful, and as queen she became protective of her royal power. The Spanish Ambassador stated that Elizabeth gave orders and ruled her court as powerfully as her father. However, Elizabeth was arguably more involved in the day-to-day running of the country than her father had been.

The Privy CouncilA group of men, known as councillors, who provided the monarch with advice and helped with the running of the country. advised the Queen and helped run the country on a day-to-day basis. Mary typically had around 40 councillors during her time as queen. Elizabeth believed that having such a ‘multitude’ of councillors would make decision making ‘disorder[ed]’ and confusing.

She reduced the size of the council, keeping some of Mary’s councillors and adding new, loyal and capable members. This included William Cecil, who became Elizabeth's chief ministerThe most senior servant of the monarch, who held a great deal of influence over their decisions. Thomas Wolsey held this position under Henry VIII, while William Cecil was Elizabeth I's chief minister for most of her reign., and Robert Dudley, her childhood friend. Over time she replaced Mary's councillors with her own choices, who devoted their lives to helping her run the kingdom.

Who were Elizabeth's key councillors?

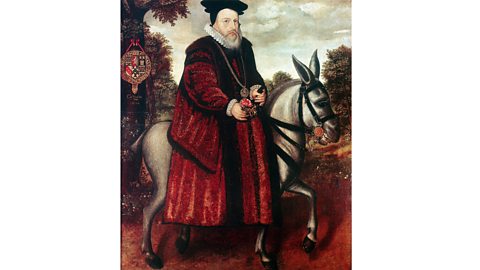

Image caption, William Cecil was Elizabeth’s first appointment. He became Secretary of State and a leading councillor. Over the course of 40 years, they developed a strong working relationship, and Elizabeth valued his opinion. Like Elizabeth, Cecil was a moderate Protestant and was not keen to go to war. He worked for Elizabeth well into old age, at which point his son, Robert Cecil, took over some of his duties.

Image caption, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was a childhood friend of Elizabeth. Like her, he had also been imprisoned under Mary I, and had seen family members executed. Dudley was a more radical Protestant than Elizabeth, and he pushed for military action against Catholic Spain. He put himself forward as a potential husband for Elizabeth, and there were constant rumours of a romance between the two.

Image caption, Sir Francis Walsingham became a key councillor after serving Elizabeth as a Member of Parliament and ambassador. He was a radical Protestant and extremely critical of Catholicism. Along with William Cecil, he ran a sophisticated spy network across Europe to ensure Elizabeth’s safety. He had spies everywhere, including in the Vatican, where the Pope lived. He uncovered many plots against Elizabeth and regularly allied with Dudley on matters of religion.

Image caption, Sir Christopher Hatton was highly educated and became Lord Chancellor in 1587. He was a moderate Protestant and felt some sympathy towards Catholics. He was loyal and hardworking and organised Elizabeth’s progresses, which were summer journeys around the country to visit her people. Hatton also helped Elizabeth to control her Parliament.

Image caption, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, was the stepson of Robert Dudley. Like his stepfather, he was a radical Protestant and a skilled soldier. He was also quick to anger and overly ambitious. He made a name for himself fighting against Spain, but Elizabeth fell out with him when he failed to crush an Irish rebellion on her behalf. He also fell into rivalry with Robert Cecil, William Cecil’s son. In 1601, he was executed after attempting to rise up against Elizabeth’s government.

1 of 5

The question of marriage

Tudor England was a patriarchyA society in which men rule and hold power over women. society. Women were perceived to be physically and emotionally inferior to men. They were also thought to be less intelligent. Women’s lives were controlled by their fathers, and later by their husbands.

Women were considered to be unfit to rule without a man’s help. Everyone expected Elizabeth to marry as part of her duty as a woman, but also so that she would provide an heir to the kingdom.

However, as some of Elizabeth’s female relatives discovered, marriage could also prove to be dangerous in Tudor times.

After the death of Edward VI, Elizabeth’s cousin Lady Jane Grey had been forced to marry Guildford Dudley. She was then forced by her father-in-law, John Dudley, to claim the throne of England. This led to her being executed when Mary I took the throne from her. Mary married King Philip II of Spain. This marriage dragged Mary into disastrous wars against France, and led to rebellions from people fearful of Philip seizing control of England.

If Elizabeth married an Englishman, he would automatically be of lower status than her. However, marrying a foreign prince could mean dragging her kingdom into foreign wars. Even worse, he could try to seize power.

Despite these dangers, Elizabeth’s ParliamentElected members of the House of Commons, and the House of Lords, who helped the King to pass laws. and councillors tried to convince her to marry. Many suitors asked for her hand, including Robert Dudley, her childhood friend.

Elizabeth said no to all of them. She chose to rule as a lone queen and used powerful speeches to warn Parliament and her councillors not to force her to wed. She even told Parliament that she would rather be thrown out of the kingdom in only her petticoats than be forced to marry.

Elizabeth used her decision not to marry to her advantage, portraying herself as devoted to the kingdom and married to her people.

Religion under Elizabeth I

- Elizabeth's father, Henry VIII, had broken from the Catholic Church in Rome. His main motivation for this was to get his marriage annulled and have a male heir: it was an argument about power and the successor to the throne, not a definite move towards Protestantism. Henry remained a Catholic until the end of his life.

- Edward VI built on the changes that his father had started, and became a devout Protestant.

- Mary I restored Catholicism to England, attempting to make the country's religion the same as it had been at the beginning of Henry's reign.

- At first, Elizabeth I attempted to forge a 'middle way' for religion in England. She wanted to create an inclusive Protestant Church that allowed her to be in a position of authority, while enabling former Catholics to feel that they could follow the new approach to religious worship. Later in her reign, however, she persecuted Catholics, and by the time she died England was a Protestant country.

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement

Elizabeth faced an incredibly difficult situation. One of the reasons Henry established the Church of England was to marry her mother, and she had been raised as a Protestant. In fact, many of the Protestants who had fled the country during Mary’s reign returned to England when Elizabeth became queen. But at the same time, Elizabeth had inherited a largely Catholic government and Parliament, and she needed to work with them for the good of the country.

With the help of William Cecil, Elizabeth began to reinstate a more moderate form of Protestantism in England. She used Parliament to pass laws to create the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. This settlement made England Protestant, however it compromised on certain areas of religion in the hope of keeping England’s Catholics within her new Church. As a result, Elizabeth’s settlement has also been called the ‘middle way’.

- As part of her Religious Settlement, Elizabeth was titled Supreme Governor, rather than Supreme Head, of the Church of England. She might have chosen this title to appeal to those who thought that a woman could not be head of the Church, or that only the Pope could be head of the Church.

- All clergy and royal officials were required to swear the Oath of Allegiance to the new Church of England, or they would lose their jobs.

- All churches were to be uniform, or look similar. Any Catholic paintings were replaced with a royal coat of arms. Everyone was required to attend the new Church, whether they were Catholic, Protestant or Puritan. If they did not, they would be fined.

- A new Book of Common Prayer, written in English, was to be used by all. It had been written in the hope that it would satisfy both Catholics and Protestants.

- Church music was allowed, as it had been in Catholicism.

- Priests were to wear vestments, or special clothing, which radical Protestants hated. Protestant priests were also allowed to get married.

How successful was Elizabeth's Religious Settlement?

Throughout the 1560s, the response to Elizabeth's settlement was generally positive, with Elizabeth largely able to bring stability to England after a period of huge religious upheaval.

Historians might argue that the settlement was a success for several reasons:

- The majority of priests agreed to take the oath of allegiance.

- Of 9,000 priests in England, only 250 lost their jobs.

- Many very devout Catholic bishops resigned, so they did not represent strong opposition to Elizabeth's new approach.

- Elizabeth did not strictly enforce the fines that Catholics were to pay if they refused to attend church.

- The Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker, was a widely respected moderate Protestant.

Despite this early success, it is important to remember that opposition to the settlement increased over time. By the 1570s and 1580s, Catholic opposition was growing, and some Puritans tried to adapt aspects of the settlement in light of their own beliefs.

Elizabeth's foreign policy

Europe

Elizabeth initially wished to maintain a peaceful relationship with other European countries. War was expensive and England was in debt. Elizabeth ended the war that Queen Mary of England and King Philip of Spain had begun with France. Elizabeth, though Protestant, also sought to build a positive relationship with Catholic Spain, and Philip, but this did not last.

Philip controlled a vast empire, stretching from Spain through the Netherlands to the Americas. There was a strong Protestant population in the Netherlands. From the 1560s to the 1580s, Protestant rebels rose up against Catholic Philip’s control of the region. Elizabeth eventually bowed to pressure from men like Robert Dudley and provided support to the rebels. Earlier in her reign, Elizabeth had rejected Philip as a possible husband.

All of this angered Philip; he was also horrified by the execution of Mary Queen of Scots, in February 1587. In 1588, Philip sent a large number of ships, known as an Armada, to invade England. It was defeated by a combination of storms and the English having ships that were better suited to the conditions. However, the war against Spain would continue into the reign of James I.

The beginnings of the British Empire

The origins of the British Empire can be traced back to the foreign policyA monarch or government's approach to interacting with nations abroad. of the Elizabethan era. In 1585, the first English colony was founded in North America when Sir Walter Raleigh organised a small settlement at Roanoke, in what is now the US state of Virginia. Although Roanoke failed, a permanent colony called Jamestown was set up nearby in 1607. Historians are unsure as to whether the name ‘Virginia’ comes from Elizabeth’s nickname, the ‘Virgin Queen’, or whether it's a word from the language of the native Algonquin people.

During her reign, Elizabeth supported several privateersPirates who sailed to raid foreign ships with the permission of their monarch from around 1560-1856.. These men were effectively pirates that were supported by the monarch. They stole treasure from Spanish ships, whose crew had generally previously stolen it from Latin America. This led to some privateers becoming rich, and Elizabeth made money from their activities. Some of these privateers, such as John Hawkins and Francis Drake, were involved in trading enslaved people from West Africa. However, it wasn’t until after the Elizabethan era that England became one of the world’s largest traders in enslaved Africans.

Towards the end of her reign, Elizabeth granted a charter to a group of London officials, merchants and investors to send ships to an area that was then called the ‘East Indies’. This eventually became the East India Company, which went on to colonise much of India.

How did Elizabeth deal with rebellions?

Elizabeth faced several rebellions against her during her reign. These largely centred around religion and her Catholic cousin, Mary Queen of Scots.

In 1568, Mary Queen of Scots was forced to flee Scotland. This was because she was rumoured to have been involved with a plot to murder her second husband. Though she was Catholic, the powerful men in her kingdom were Protestant. Mary fled to England in the belief that her cousin would support her.

In England, Mary became a focus of Catholic plots and rebellions against Elizabeth. The first of these was the 1569 Revolt of the Northern Earls. Nearly 5,000 men in the North rose up to return England to Catholicism and place Mary Queen of Scots on the throne.

Though this rebellion was crushed by Elizabeth’s forces, three further plots to place Mary on the throne followed. After being personally implicated in one of the plots, Mary was convicted of treason and executed in 1587.

Overall, Elizabeth faced fewer rebellions than previous Tudor monarchs, and those that did occur were never quite serious enough to prevent her from putting her new policies and ideas in place.

Why did Mary Queen of Scots become a threat to Elizabeth?

Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scots at first had a mutual respect for one another, although they never met in person. Despite this, Mary later became a threat to Elizabeth. This was because Mary was also descended from the Tudors, as the great-niece of Henry VIII. As Mary was Catholic, many Catholic people and foreign rulers supported Mary as an alternative monarch to the Protestant Elizabeth.

Elizabeth and Ireland

In the 1540s, King Henry VIII had announced himself ‘King of Ireland’. The Tudor monarchs attempted to enforce English law and governance across the country. This led to uprisings as the Irish pushed back. In 1593, Irish leader, Hugh O’Neill, challenged English rule in Ireland, raising a large army and fighting English soldiers sent to the island. O’Neill wanted to end English attempts to rule Ireland. While he achieved many victories against the English, he was eventually defeated. His rebellion ended after the death of Elizabeth.

O’Neill’s rebellion also contributed to a rebellion led by Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. Robert Devereux was sent to Ireland to crush O’Neill’s rebellion. Instead of fighting, Devereux signed a treaty, which infuriated Elizabeth. On his return to England, Devereux was sent away from court. He began a rebellion against Elizabeth in London, claiming he needed to take control and overthrow the men around her, such as Robert Cecil, his rival.

Who was Hugh O'Neill?

Hugh O’Neill was born into the powerful O’Neill family but was fostered by an Anglo-Irish family after his father was assassinated.

He initially cooperated with Elizabeth, but after he became the head of the O’Neill family he began to fight the English openly.

His win at the Battle of the Yellow Ford, in Ulster, sparked a general uprising against the English, which spread across the whole of Ireland. The Pope sent Spanish troops to help O’Neill, who was Catholic, but he wasn’t able to defeat the English completely, and free Ireland from their control.

In early 1603, Elizabeth asked the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Sir Charles Blount, to start negotiating with O'Neill and the rebels. As Lord Deputy, Blount was Elizabeth's representative in Ireland. When Elizabeth died, Blount did not tell O'Neill, and waited until the negotiations were over to reveal the news. O'Neill eventually surrendered on 30 March 1603, six days after Elizabeth's death.

He kept his lands in Ulster, but his status and independence had been seriously weakened. In 1607, O’Neill, the Earl of Tyrconnell and about 90 followers left Ulster and travelled to Rome. Outlawed by the English, O’Neill spent the rest of his life in Rome, where he died in 1616.

Test your knowledge

GCSE exam dates 2025

Find out everything you need to know about the 2025 GCSE exams including dates, timetables and changes to exams to get your revision in shape.

More on The Tudors

Find out more by working through a topic

- count4 of 5

- count5 of 5

- count1 of 5

- count2 of 5