Sometime around the end of summer, it dawned upon most Democrats, and the elite of both parties, that they — okay, we — inhabit a different political universe than does the rest of the country. In our world, Donald Trump is a surreal authoritarian buffoon whose presidency is too nightmarish to contemplate, except perhaps as an abstract intellectual exercise to bolster whatever argument one wishes to make about larger trends in American society. Hillary Clinton is deeply familiar, liked by some, loathed by many, and caught in a vortex of mutual paranoia with the news media that leads her into errors of secrecy. But her flaws, as the conservative but Clinton-endorsing pundit P. J. O’Rourke put it, lie “within normal parameters,” and disagreements within the elite feel small in the face of Trump. Envisioning him as the actual president of the United States seems to us like a category error, as if a Game of Thrones character were to show up on Veep.

But as the first of the presidential debates looms, the hard numbers simply do not bear out this reality. The website FiveThirtyEight gives Trump more than a four-in-ten chance of actually, for real, winning. The Upshot, the New York Times’ forecaster, puts it at a slightly more comforting one in four, which sounds low except that, as the model’s authors point out, this makes the odds of a Clinton victory about equal to an NFL placekicker’s chances of making a 49-yard field goal. Also, the kicker has pneumonia. Citigroup recently warned that investors are underappreciating the significant risk to the economy of a Trump victory. A Trump presidency has felt unimaginable all summer long for the same reason Brexit couldn’t pass in England and Trump couldn’t win his party’s nomination: We refused to believe what the numbers were telling us.

In Washington, it is an open secret that many, probably most, leading Republican officials consider Trump dangerously unqualified. After the liberal journalist Ezra Klein called Trump “the most dangerous major candidate for president in memory,” among other insults, a “very conservative” Republican member of Congress (who has publicly endorsed Trump) called to praise him, off the record, of course, for speaking out. When Trump selected Mike Pence as his running mate, former Bush-administration official Dan Senor tweeted that Pence had once “commiserated” with him that Trump “was unacceptable.” A recent McKay Coppins story in BuzzFeed quotes a series of Republican operatives anonymously confessing their preference for Clinton. “It’s terrifying. He’s not qualified … and it’s a massive problem,” said one. “It would be terrible for America, and for the world,” warned another.

Somehow, this understanding of Trump has not filtered down to the electorate. The battle lines do not resemble those of a race between a regular politician and a freak-show buffoon. They reflect the normal Republican coalition, minus heavy defections from college-educated white women, against the normal, slightly larger Democratic coalition, minus the usual enthusiastic youth support. At the official level, public GOP defections are confined mostly to a handful of blue-state politicians and prestige print pundits. The party’s political and messaging apparatus, from Fox News to talk radio, remains pro-Trump, albeit often with muffled reservations.

The Republicans who hope to inherit their party’s leadership after Trump are trying to signal disagreement just loud enough for insiders to hear without being audible to their mostly pro-Trump voters. When Trump praised Russian dictator Vladimir Putin as a strong leader, the most recent affirmation of his long-standing belief that strong leaders are those who crush their opposition, Marco Rubio replied, “My sense is those views will probably change once he understands better who Vladimir Putin truly is — that’s my hope.” Yes, surely Trump’s authoritarian impulses will be tamed once he commands the Executive branch of the United States government.

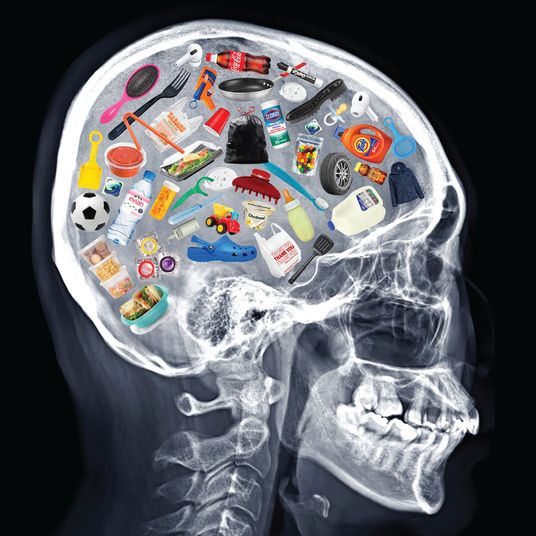

The view of Clinton that has been refracted to the electorate may be even more distorted than the image of Trump. The generation-long psychodrama pitting Hillary Clinton and her husband against the media has played out in the contested margins of propriety and legality. The Clintons habitually push the boundaries, collecting speaking fees from sources they should be shunning, refusing to disclose information, and so on. Voters with clear memories of the Clinton administration understand news reports about her blunders within this context — it’s all just more exasperating corner-cutting.

Voters too young to remember the first Clinton presidency have come away with a very different impression. Many of them received their introduction to Hillary Clinton through Bernie Sanders, who presented his opponent as the “bought and paid for” representative of a “rigged” system. Sanders has always used hyperbolic terms like this in expressing his left-wing indictment of the power of entrenched wealth, but the metaphor may have been lost on young voters who came away regarding the Democratic nominee as literally a criminal. Polls show that voters under 30 loathe Trump but have not given Clinton anything close to the margins enjoyed by Barack Obama in either of his two elections.

The conventions of the political media have deepened this impression. Campaign coverage at a newspaper or a television network is structured like so: A set of reporters is assigned to each candidate, and they report on their assigned candidate more or less independently of each other. The arrangement works reasonably well in normal elections. In 2016, it has broken down. The Trump reporters have spent months drinking from the fire hose of Trumpian outrage, which they have attempted to funnel into a digestible stream for their audience. Clinton-assigned reporters have produced their own stories focusing heavily on the emails and the Clinton Foundation, some taking her to task fairly and others laden with insinuations of guilt even though the facts suggest otherwise.

Suppose one decided to disregard the mountains of evidence against Trump — his racism, misogyny, bullying, love of dictators, fraudulent business practices, constant lies, complete ignorance of policy, etc. — and focus a comparison entirely on those grounds where Clinton herself is most vulnerable: disclosure and financial ties. Even in those areas, Trump’s misdeeds dwarf hers. His refusal to share his tax returns is without modern precedent. He has used his foundation for personal profit and political bribery. He has stated that if he were elected, his children would run his company, which is based mainly on licensing his name — a recipe for flamboyant corruption on the scale of post-Soviet kleptocracy. And yet the parallel scrutiny of both sides has yielded a portrait of two nominees who, from a hazy distance, seem flawed in roughly equal measure. Clinton’s net favorable rating (negative 15) is just a bit better than Trump’s (negative 20). In polls, she clings to a narrow lead.

The probably fortunate news is that there is a mechanism in place to prod the public into judging the candidates against each other: the presidential debates. In fact, they are likely the last chance to alter the trajectory of the campaign. Four years ago, Barack Obama’s poorly received first debate performance and subsequent recovery created the only real drama in an otherwise steady race. The Trump-Clinton debates may matter even more. Trump will bring certain advantages. He has an adolescent bully’s instinct for zeroing in on his target’s most evident weakness (often a physical trait) that has been honed over years of training. On the other hand, he knows nothing about public policy, cannot be bothered to learn, and faces a foe with an encyclopedic knowledge of all subjects foreign and domestic. It is not too much to suggest that the fate of the republic might hang on Clinton’s rising to the task.

*This article appears in the September 19, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.