When Duncan and Griffin Cock Foster met Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss last year, it was inevitable that they would have a lot to talk about. Both sets of siblings are twins. Both had been rowers. Both had founded companies to make money in the world of blockchain technology. In other words, both are literal, actual tech bros.

“We were telling them this story about how we realized we could get a lot more out of teaming up as twin brothers working together,” Griffin recalled of the Cock Foster–Winklevoss summit. “And they were like, ‘Oh yeah, we hear you on that.’ ”

The Winklevosses — Mark Zuckerberg’s Harvard schoolmates, immortalized in The Social Network, who famously sued him for stealing Facebook and later became bitcoin billionaires — were then about to buy the 24-year-old Cock Fosters’ start-up, Nifty Gateway, through their own cryptocurrency company, Gemini. Part of the acquisition payment was to be, naturally, in bitcoin.

“The funny part,” Duncan added, “is [in high school] we went and saw The Social Network, and everyone was like, ‘Wow, you guys kind of look like those twins from that movie; you guys should row too.’ And that’s how we started rowing. I mean, we didn’t make it to the Olympics.”

It was a recent morning, and the brothers, 25, were sitting in the Soho apartment they share. “We were, like, okay at rowing,” Griffin added.

“I was pretty good,” Duncan said.

We are now at the stage in the internet’s evolution when the low-hanging disruption fruit has been plucked. Coding prowess and world-beating ambition may no longer be enough. The remaining opportunities may be lucrative, but they can be dauntingly esoteric. The brothers, who grew up in Seattle with parents who knew lots of people at Microsoft, began coding in sixth grade. “Most of what we do these days is explain ‘nifties’ to people,” Griffin said, as he and Duncan tried to explain nifties to me.

“The elevator pitch I always give,” offered Duncan, who wore glasses and had slightly less buoyant hair than his brother, “is that a nifty is a fundamentally better digital good.”

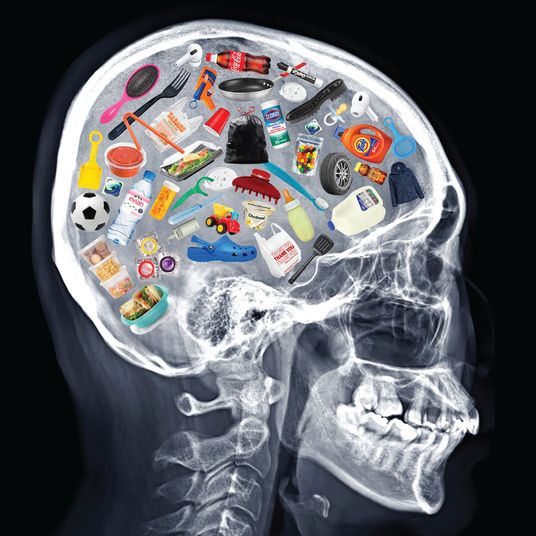

This is helpful if you already understand what a digital good is: a virtual object made of ones and zeros that you can see only when it’s rendered onscreen. Based on the same blockchain technology as cryptocurrency, nifties are a departure from that. Short for NFTs (non-fungible tokens), they are unique digital objects you can buy, own, and sell. The brothers’ go-to analogy is that nifties are like “digital Air Jordans.” “If I own a pair of shoes and Nike shuts down, I don’t expect that my shoes would just disappear,” Duncan said. “We expect our items to behave a certain way, and past digital items have not.”

The Cock Foster twins started Nifty Gateway to mainstream what had been a highly technical subculture by, among other things, allowing civilians to buy nifties (on the Nifty Gateway website) with credit cards. Last summer, when they sold the company to Gemini, the Cock Fosters’ lives underwent a dizzying change. Their company was less than a year old, and they were suddenly able to move from a small apartment in San Francisco, in which they shared a bunk bed, to a spacious two-bedroom in Manhattan, which they have nicknamed Cockfosters. “It’s a canonical Soho loft,” said Duncan, gesturing at the high ceilings, scuffed wide-plank floors, and dangling Edison bulbs in the living room, which overlooks Mercer Street. “I love the word canonical,” he added.

The Cock Fosters see big things ahead for nifties. The brothers’ stated mission is to have 1 billion people collecting them. They talk about how nifties could one day be paired with physical assets, so you could use a digital token to prove your ownership of a piece of, say, real estate. But in these early days, the use cases can seem generationally exclusionary. The first nifty to go viral was CryptoKitties, a game featuring a digital feline you can collect and breed. A single CryptoKitty has sold for a record $170,000, and venture capitalists including Union Square Ventures and Andreessen Horowitz have put money into the company behind the game. “CryptoKitties was the thing that got my attention,” Duncan said. “The amount of money people were spending on CryptoKitties was remarkable.”

Moving to New York made sense for the Cock Fosters for a couple of reasons. Becoming part of Gemini, which has its headquarters in the Flatiron District, gave them instant access to the heavy-duty technology required to safeguard users’ digital assets. Equally appealing was the fact that New York is the center of the art world, because the brothers see nifties’ first mainstream application being rare digital artworks and collectibles. MLB has already launched Champions, a line of bobbleheadlike crypto-collectibles, and the NBA has a similar collection in the works.

On an L-shaped configuration of tables in one corner of their loft, the twins had set up a gallery of five flat-screen monitors, each displaying a different Nifty. The first was Crypto Punk 4445, one of a collection of 10,000 unique pixelated cartoon heads with earrings, mohawks, and the like, and owned by Duncan. The next was a Cryptokitty, named Cheeky Achoobah, owned by Griffin. The third Nifty on display was titled “Shiny Cameron Winkelvoss #1.” With spiky blond hair, an earring, and a t-shirt, it didn’t look much like its namesake, but even the employees of Gemini needed to have Nifties explained to them, so the Cock Fosters had made a lunch presentation to the staff during which they gave away fifty digital Winkelvii renderings, which Duncan had designed himself using an online kit.

This month, the brothers are launching what they call Nifty Gateway 2.0, which includes a marketplace to buy and sell nifties along with several nifties by noted artists with whom they’ve partnered. The brothers sketch a vision of a fully niftified world: “We want Supreme making nifties,” Duncan said. “We want some CryptoPunks in the permanent collection of MoMA.”

It’s a world, in their sunny view, where nifties could one day be more valuable than physical art. “If you critically rate what makes art valuable as an asset, which is authenticity, liquidity, and longevity,” Duncan said, “then nifties blow traditional art out of the water in all three of those categories.” The room we were sitting in was hung with a handful of spattery, Jackson Pollock–esque oils on canvas, and I pointed out that nifties would never be able to offer the physical textures of real-world art. “We’re actually working on a 3-D nifty display screen,” Duncan said — an app to run on existing hardware, which would enable creators to make holographic art. “I’m a big fan of my friends’ art,” he said, “but I don’t know if I want to display any more physical art from a certain point going forward.”

Last June, the brothers toasted the sale to Gemini by throwing a big dinner party at their loft. They gave out party favors to their 34 guests, a QR code leading to a limited-edition nifty they’d commissioned from an artist friend. Starting at 7 p.m., it shows a nighttime version of the apartment, and at 7 a.m., it switches to daytime. (Exactly what they could do with it beyond calling it up online, to gaze at when the mood strikes them, is one of the less developed areas of niftydom so far.) “The only way to get it was to attend that dinner party,” Duncan said.

“The dinner party was a proof of concept also,” he added. “I like to think that in ten years, everyone will be commissioning artists to create nifties to give away at a dinner party.”

*This article appears in the March 2, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!