Over the past week, protests and riots in response to the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis have been met with increasingly menacing calls to restore order. But chaos isn’t going anywhere soon. Order, in this context, just means forcing chaos back where it belongs. There are positive signs for the near future, especially if one understands the dissent as aimed primarily at reducing police violence. Public sentiment is on the side of the dissidents; a recent Monmouth poll found that more than half of Americans thought the torching of the Minneapolis police’s Third Precinct station on May 28 was at least partly justified. Repudiations of Floyd’s manner of death, under the knee of now former officer Derek Chauvin, have been mostly bipartisan. Minneapolis schools have kicked out the police department, and the city council has announced it may rebuild the force from the ground up.

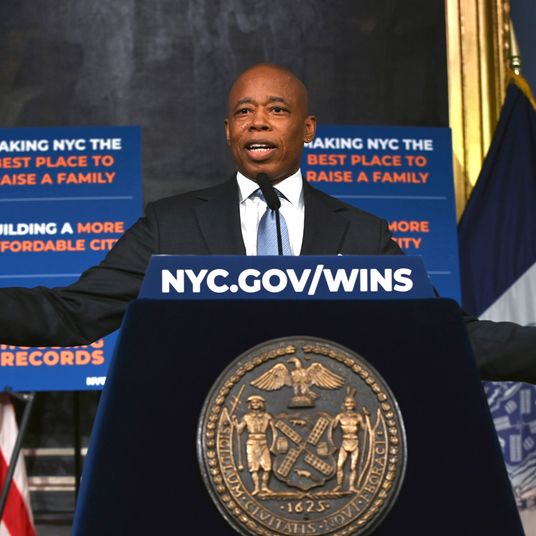

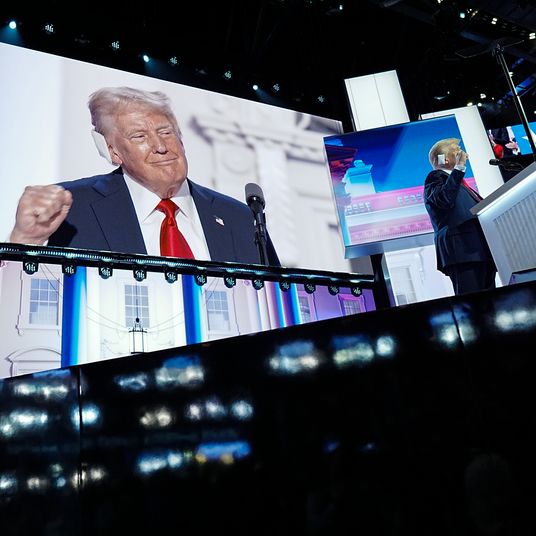

Yet when President Trump came out of hiding on June 1 to demand in a conference call that America’s governors “dominate” the dissidents, and threatened to deploy the military to their cities if they couldn’t, he could also claim to be speaking for most of the country: In one poll, nearly 60 percent of Americans said they supported dispatching soldiers to help local police quell the unrest.

This may seem like a contradiction. To support the protests but endorse their policing by light infantry looks like ideals at odds and could suggest anything from a polling quirk to a refusal to contemplate the contradictions of one’s political impulses. But the split is plausible through a particularly American understanding of order: Disruptive tension is put down by violence without being properly resolved, even when its causes are deemed worthy in principle. What qualifies as “disruptive”? That differs by person and era, but the word rioting is a constant across generations. This fits its social function. A riot is not a tactic to gain widespread sympathy but an expression of how inadequate other efforts have been. The same standard is routinely applied to more peaceful protests, though, and is used to make appeals for order, which then becomes the prerequisite for resolving dissenters’ grievances. First order, then reform — as though the structure of order weren’t the very thing that protesters demand reforming.

One result is that the social problems civil-rights activists sought to rectify more than 50 years ago are still urgent ones. To some, the events of the past week have echoed the struggles of the past. To others, it looks like the beginning of the future.

But history suggests that, more often than not, grievances like these are addressed piecemeal, if at all, because the choice as originally presented was a lie: Order was never required as a building block for good-faith negotiations; it was a pretense for rerouting chaos back into the lives and communities of the dissenters, where it could be contained. And just as this dynamic has endured into the Black Lives Matter era and beyond, so too has its enforcement tactics. Sending combat troops into American cities to contain protests would mean another dramatic escalation of the violence that is already being used widely by police and that, in the past week, has expanded to include targeted beatings of unarmed protesters, their detainment on specious grounds, the use of chemical weapons, and even the killing of dissidents. To understand how much more toxic this dynamic can get, we need only be patient.

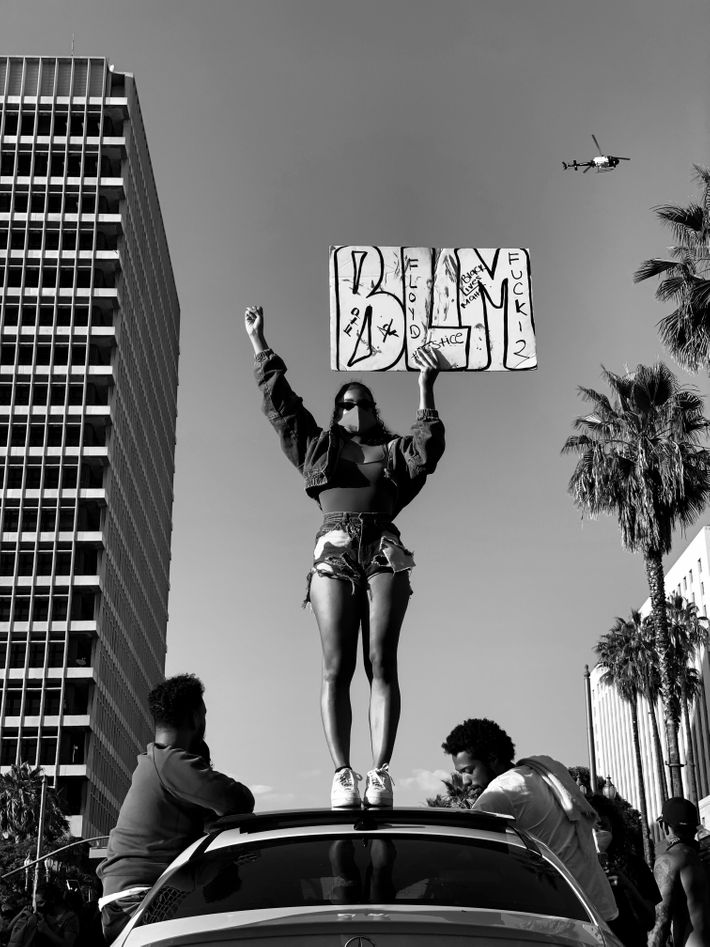

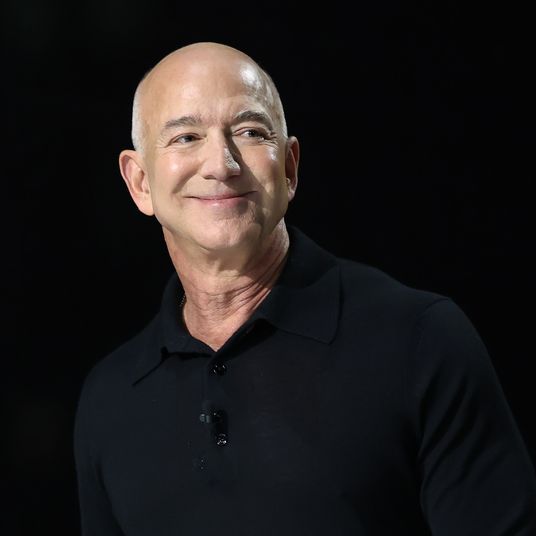

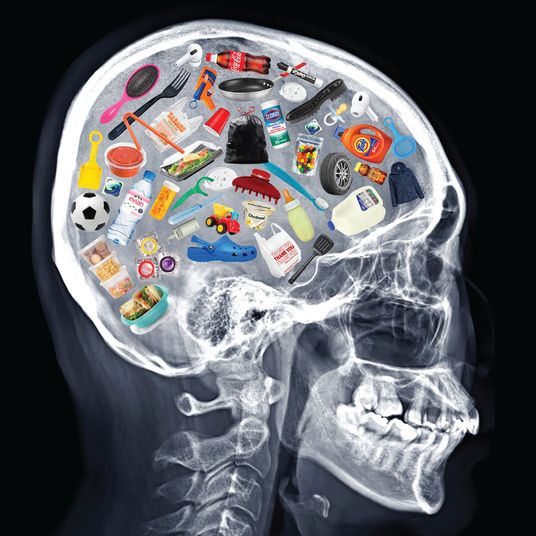

In the meantime, nonviolent BLM protesters demanding an end to racist policing are in the streets alongside black-bloc vandals, even as the less ideologically aligned set fires in anger and pillage stores out of desperation for goods long denied or, in other cases, in an opportunistic loot-grab sanctioned by the lawlessness of the law’s enforcers. What unifies these and other factions is the force that antagonizes them: a governing order that demands their submission while reveling in their destruction. The black people and young people who compose the lion’s share face not only police violence with regularity, in the case of the former, but among the most dire generational economic prospects in modern U.S. history, all in the midst of a world-stopping pandemic. These are rendered starker by the ballooning assets of the country’s billionaires — a 15 percent overall wealth increase since March, even as millions of Americans have lost work. The near future stands to see a compounding of the resultant phenomena. Food lines, coronavirus-safety measures, the simmering desperation of the unemployed, all are poised to become the purview of armed agents of the state in some form, if they aren’t already.

This will seem outwardly as if order is being kept. But people who are harassed, detained, arrested, beaten, and killed by law enforcement and the military do not hurt in a vacuum; these encounters reverberate outward in the form of work lost owing to jail time spent, fines and fees levied by the state as restitution for disobedience, psychological damage, medical bills accrued, families destroyed because of lives lost. For many Americans, this will be viewed as acceptable because it targets groups they think deserve it.

Even so, these protests may well produce more just and less violent law enforcement, at least in some places. But the degree will depend on Americans controlling their impulses — meaning less the demonstrators than those who support parachuting a military occupation into cities to crack down on protesters at the behest of the most erratic, unhinged president in recent memory. They’ve had an inauspicious start. While polling suggests some people do support reform, it also suggests reform with preconditions, namely, recontaining through violence the chaos of human lives that are already under siege. We’ve seen where that kind of escalating state brutality gets us. The challenge today is to try something whose failure isn’t already assured.

*A version of this article appears in the June 8, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!