Other than Wilco’s panic-attack-addled, experimental maestro Jeff Tweedy and the perpetually inebriated yet strangely affecting torch singer Greg Dulli, there are few eccentrics left in rock. Even “alt-rock” is crowded with well-groomed, inoffensive retro bands like the Hives, Franz Ferdinand, and Jet. Pop critic Jon Savage’s description of the British rockers the Jam circa 1977—“their image is of strict uniformity/blandness … White shirts/ black ties/suits … cold, regular”—seems like an eerily apt summation of rock’s current conservatism.

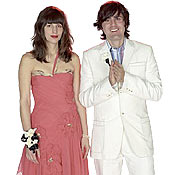

The Fiery Furnaces—a New York–based band led by siblings Eleanor and Matthew Friedberger—are anomalous among the rock dandies. They make music that, though heavily steeped in the past, is neither cold nor regular nor retro. On their 2003 debut, Gallowsbird’s Bark, the Furnaces romped through blues, ragtime, electronic music, and rock like brilliant buskers. They didn’t reference different eras for the sake of irony or to display their savviness about pop history; instead, they were passionate curators who immersed themselves so deeply in the past that they brought it to life.

On Blueberry Boat, the Furnaces’ second album, the band take their experimental ethos even further without sacrificing the emotional power of their debut. The album’s eleven-minute opener, “Quay Cur,” has the Friedbergers trading verses about a boat that’s gone ashore, backed by music that shifts from squishy-sounding, almost aqueous drum-machine beats to galloping guitar playing. This could come across as precious and overly whimsical, like Jon Brion’s Beatles-esque productions for Aimee Mann, if not for the intense back-and-forth between the Friedbergers. Their exchanges—as well as the radical transformations of the music backing them—keep the song from collapsing into quirkiness.

The traditional songs of Blueberry Boat maintain the tricky balance of “Quay Cur.” On “My Dog Was Lost But Now He’s Found,” the Friedbergers upend the song’s simple premise with odd phrases like “I went to the Super K have you seen any recent stray” and music that’s gloriously, kaleidoscopically shape-shifting.

Even when it threatens to get carried away by its own eccentricity, Blueberry Boat is held together by Eleanor’s vocals, which range from a scratchy, vulnerable yelp to a kind of breathless gulp as she tries to keep up with the band’s rambling, Dylan-esque lyrics. It’s a voice that’s reminiscent of the forceful female voices of the seventies, like Carole King and Stevie Nicks, not the passive wispiness of the singer-songwriter set today. Indeed, when the band played the Brooklyn club Northsix a few months ago, Eleanor held the audience rapt, though she barely addressed it. She has that same effect on Blueberry Boat—almost improbably strange, remote even, but with a humanness in her voice that keeps you with her.