We bring to old movies everything we know about their stars’ and directors’ careers and lives, and everything we know about movie history since the making of the one we’re watching. In the case of the 1957 Paths of Glory, playing in a glistening new black-and-white print at Film Forum December 2 through 8, this context adds to the pleasure and stinging irony of this elegant yet blunt production.

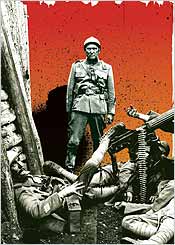

Set primarily in the trenches of World War I’s western front, Paths of Glory stars Kirk Douglas as the French Colonel Dax, a principled soldier faced with an impossible order. Leading a small group of exhausted, underequipped soldiers, he is commanded to take “the Ant Hill,” a heavily fortified patch of land occupied by seemingly vast numbers of German soldiers. The goal is hopeless from the start; the French are quickly driven back in a bloody rout. But the reaction of Dax’s superiors seems even more cruel: Colonel Dax is ordered to pick three of his men to stand trial on grounds of cowardice; they are to be made examples of, and executed. Why? Because, as the airily distanced General Broulard, played with superbly blithe insouciance by Adolphe Menjou, says, “These executions will be a perfect tonic for the entire division … One way to maintain discipline is to shoot a man now and then.” Dax is placed in a morally vexed position but carries out the order, and three luckless soldiers are selected.

Adapted by the potboiler king Calder Willingham and pulp-novelist supreme Jim Thompson from a best-selling novel, Paths of Glory could have taken an alternate title from Thompson’s greatest hit, The Killer Inside Me: Nearly every character in Paths of Glory, from General Broulard to Colonel Dax to the hapless sacrificial soldiers, grapples with the implications of killing and dying, but never at the expense of cinematic hustle and flow. Never again would director Stanley Kubrick—who’d succumb immediately afterward to auteur languor and excessive perfectionism—be so concise as he was in the editing of this stark 86-minute film. The long tracking shots of Douglas, his upper body an inverted triangle of muscle and forward-momentum energy, striding swiftly through the trenches of his troops’ encampment, will give you goose bumps of anticipation. If bullets and shells explode around him, Douglas gives off an equally explosive power. Watching him, I thought, This is what his son Michael would look like with better posture and more charisma.

Paths of Glory is all about that greatest of all movie subjects: power. Menjou’s General Broulard and his even more arrogant cohort, General Mireau (the sneering George Macready), occupy impossibly ornate palaces as command headquarters—to them, soldiers are like the grains of salt they spill on silk tablecloths. They think the anguish expressed by Douglas’s Colonel Dax isn’t genuine, that he seeks a promotion (i.e., more power) rather than a reversal of their absurdly maleficent execution order. (They are, of course, wrong: Douglas’s famous clenched jaw, expressing enraged frustration, was never put to better use.) The condemned men—played by Joe Turkel, Timothy Carey (the merciless murderer in Kubrick’s previous thriller, The Killing), and Ralph Meeker (who’d already been Mike Hammer in Kiss Me Deadly)—are entirely powerless, pawns with varying degrees of dignity.

Kubrick is quoted in Norman Kagan’s 1972 book The Cinema of Stanley Kubrick as saying that war is “one of the few remaining situations where men … speak up for what they believe to be their principles.” Recent war films ranging from Three Kings to the documentary Gunner Palace—as well as Kubrick’s own final work in the war genre, 1987’s Full Metal Jacket—suggest just the opposite: that men and women are systematically stripped of their principles by their government and are sent off to die without much in the way of moral, motivating inspiration.

In Paths of Glory, General Broulard proclaims his patriotic motives to bray, “There are few things more fundamentally encouraging and stimulating than seeing someone else die.” He was talking about reviving the bloodlust ardor of his warriors. Viewing Paths of Glory in this century, you may be jarred you into thinking about how little the “stimulation” of waging war has changed. We and our leaders, like Broulard, rarely glimpse the thousands of troops who die serving their country. Yet while the distancing effect of long-range modern weaponry may cut down on the hand-to-hand combat World War I soldiers are shown engaging in here, there are still plenty of close-up, bloody confrontations endured by soldiers on the ground (shock and awe now seems a rather distant memory).

But, in other ways, Kubrick’s comment shows how different our moral battlefields look from Verdun or the Somme—present-day wars afford only those at the highest levels of command to “speak up for what they believe to be their principles.” The rest of the participants are now far more like Kirk Douglas’s Dax, compelled to attempt and doomed to fail at idealized dream scenarios of victory.

Kubrick’s perfectionism was legendary—he reportedly shot 68 different takes of the accused soldiers’ last meal in Paths of Glory, forcing the on-set chef to cook up order after order of roast duck. Jack Nicholson would later jest, “Just because you’re a perfectionist doesn’t mean you’re perfect.” And though his eye was always distinctive, it was also always divisive. Critic Louise Bruce denounced him thus: “Those who have admired the motion-picture work of this erstwhile still photographer will regret that in Paths of Glory camera angles seem to preoccupy him less than political ones.” To which Kubrick might say, “Louise who?”

Paths of Glory

Directed by

Stanley Kubrick.

Film Forum.

Through December 8.