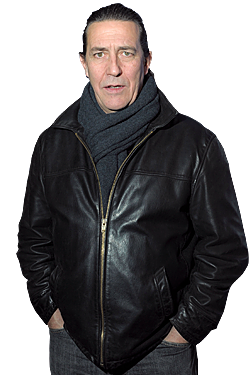

ItÔÇÖs initially a little disorienting to see Ciaran Hinds in Irish playwright and director Conor McPhersonÔÇÖs The Eclipse, which opens this week. WeÔÇÖve gotten so used to seeing the actor play domineering figures ÔÇö whether itÔÇÖs Julius Caesar in the HBO series Rome, King Herod in The Nativity Story, or a pissed-off FBI honcho in Miami Vice ÔÇö that the idea of him playing a mopey woodworking teacher and literary-festival volunteer feels like a bit of a stretch. But damned if this offbeat bit of casting doesnÔÇÖt work: ThereÔÇÖs something quietly riveting about Michael Farr, a downbeat widower and father struggling with the recent death of his wife, as he goes about his day. ThereÔÇÖs more to Farr than just submerged guilt and quiet desperation, of course: HeÔÇÖs also convinced heÔÇÖs seeing ghosts, and this is driving him into the arms of a visiting writer (Iben Hjelje), who has written a book about them. So is The Eclipse, which was a hit at last yearÔÇÖs Tribeca Film Festival, a thriller? Not quite. As Hinds himself explained to us, itÔÇÖs more of a psychological drama with the occasional terrifying jolt. The actor talked to us recently about the difficulties of playing an ordinary guy, his long collaboration with McPherson, and the challenges of taking on a role in the new Todd Solondz film.

We always hear about how characters in films have to be active and not passive, but your character in The Eclipse certainly has some passive qualities. How do you play such an internalized role?

It can be deceptively difficult, of course, because you have to make a character interesting, but in some senses I had more to draw on for a character like this. Because in reality I am much more like Michael Farr than I am like, say, Julius Caesar. There is a temptation to give a character like this a lot of quirks and things to make him lovable. But we wanted him to feel very truthful, and the best way to do that was to just go through these emotions as myself. When I first read the script, it was very delicate and short and mysterious. But because Conor and I had worked together before, I knew there was so much more there, that he would really help me bring a psychological detail and depth to this part.

Similarly, the supernatural, thrillerlike qualities of the film also present an ambiguous and unorthodox situation. We never quite know if they are real or just psychological apparitions.

You never really know, do you? ConorÔÇÖs work often has these supernatural qualities to it, but I suppose this one really is quite a mixture. TheyÔÇÖre not so much about shock, but rather manifestations of the anxiety and desperation that we all feel sometimes. ItÔÇÖs like a panic attack, this sudden jolt of fear. In that sense, the film is really about these characters, and about the pain and guilt that theyÔÇÖre suffering. If you donÔÇÖt believe their pain, then those thriller elements will not work. So I think that even though thereÔÇÖs something open-ended about those elements, thereÔÇÖs an honesty there, too. ItÔÇÖs all about the emotional turmoil that the character is feeling. ItÔÇÖs really about the fragile state that we all find ourselves in sometimes.

YouÔÇÖve spent so much of your career playing these commanding figures ÔÇö Julius Caesar, Herod, the President of Russia, the famous writer, etc. But here youÔÇÖre a guy who is basically the opposite of those things.

I suppose itÔÇÖs strange. ItÔÇÖs hard to say sometimes why youÔÇÖre cast, isnÔÇÖt it? Because these are other peopleÔÇÖs choices. Sometimes a casting director likes the cut of your jib, or likes the way you wear a costume, and before you know it youÔÇÖre playing the Emperor of Rome and the President of Russia. Personally, the disorientation goes the other way for me: IÔÇÖm wondering how the heck I ended up playing those roles. It would be great to be that at home, but it doesnÔÇÖt work that way. Like I said, IÔÇÖm more like Michael Farr. I suppose in a way IÔÇÖm more skittish, really. But basically, my job is to try to honestly go somewhere, and to do that I have to open a lot of myself in those situations.

It works, though. Because youÔÇÖre an actor who is often deemed to have ÔÇ£presenceÔÇØ ÔÇö and as a result, even though Michael is an everyman figure, we canÔÇÖt quite take our eyes off him.

ThatÔÇÖs right. HeÔÇÖs doing the dishes now; heÔÇÖs driving a car now; heÔÇÖs watching someone give a speech now. In film, itÔÇÖs usually the camera that detects what you watch. But I like ConorÔÇÖs style of filmmaking ÔÇö he allows the audience to watch people in full-length, in a landscape that opens up as well. He lets his characters do what theyÔÇÖre going to do, and he watches them, without having all these close-ups or jump cuts or whatever. YouÔÇÖre watching the whole human being ÔÇö how their bodies react, how embarrassed they are, how comfortable theyÔÇÖll feel. I love that way of working. ThereÔÇÖs something very magnanimous about it

So much so that the landscape in this film sometimes feels like a character as well.

Yes. Having looked around at a lot of locations, Conor was very fortunate to find Cobh, in County Cork, there at the bottom of the Ireland, in this inlet. It was one of the TitanicÔÇÖs last stops, so it has a bit of history. And because the story had a lot of religious connotations and guilt, he felt it was possible that we are surrounded these things that we donÔÇÖt even know sometimes.

YouÔÇÖre also in the new Todd Solondz film, Life During Wartime, which is a sequel of sorts to 1998ÔÇÖs Happiness. And youÔÇÖre playing the role of the pedophile made famous by Dylan Baker in the original film.

I am indeed. Ten years down the line. It was a very lonely part ÔÇö apart from meeting Charlotte Rampling briefly in a bar, and the last scene I have with my son, where I ask him for forgiveness. I was playing a walking shadow of a man, a man who has gotten out of prison. HeÔÇÖs served his time, but really, heÔÇÖll be serving that time forever. Working with Todd was lovely, though, and I just saw it for the first time the other week in Dublin, and it was a really brave piece of filmmaking.