The culture’s currently crawling with Gatsbyesque figures, from the silicon ciphers of The Social Network to the “self-made” congressional candidates of the tea party. But anyone seeking this generation’s true second coming of the late, great James Gatz should take a trip to the Public Theater and see Gatz, a complete, six-hour-plus recitation/re-creation of The Great Gatsby, American literature’s enduring touchstone, as well as its fetishized golden calf. Gatz’s architects, the rightly revered downtown theater collective Elevator Repair Service, treat it like scripture, reading it end to end. That they do so with lusty irony takes nothing away from the holiness of their literary mission — in fact, it enhances it, exfoliating great gaudy barnacles of accumulated Gatsby kitsch, and forcing a reassessment of our deepest beliefs about ourselves, our culture, our most treasured illusions, literary and otherwise.

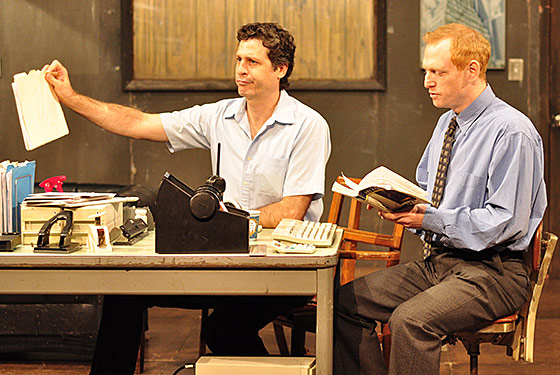

The performance is monumental, but the premise fits neatly in a manila envelope: An office drone (Wooster Group regular Scott Shepherd) enters his timelessly shabby, Charlie Kaufman–esque workplace (comically obsolete equipment, coffee-stained papers spilling from overstuffed files in huge drifts, a ground-in beigeness that pervades and depresses) and finds his desktop computer malfunctioning. Waiting for tech support, “Nick” finds a copy of The Great Gatsby on his desk and begins to read. And read. And read. Eventually, his co-workers join in, first contributing random lines of dialogue that dovetail with their never-overliteral office duties, then falling deeper and deeper into their destined roles: a big-shouldered warehouse type (Gary Wilmes) becomes Ivy League thug Tom Buchanan, a sleek front-office smiler (Victoria Vazquez) develops into Gatsby’s fatal inamorata, Daisy, and a sporty, sneakered young floater (Susie Sokol) turns into sly pro-golfer Jordan, Nick’s slippery summer squeeze.

And then there’s Gatsby (the remarkable Jim Fletcher), the last to come aboard: He’s older, odder, balder, and less beatific than the golden boy whom Central Casting has planted in our minds. Tellingly, his character is officially credited in the program as “Jim.” Tall, with a grim blond pediment of a brow, an Easter Island forehead, and an inability to fake a human smile, Fletcher’s “Jim”/Gatsby is, in aspect and awkwardness, closer to Frankenstein’s monster. To call him a downsized Gatsby would sell his strange, diffident charisma short: He’s certainly a Gatsby for a socially amputated era. But beyond that, he’s perfectly wrong for Gatsby — and I mean that as the highest compliment. Watching him stare at the green light across the bay (here a battery-status LED on a wall-mounted smoke alarm), we see no operatic yearning, only the dawn of new confusion, fresh chagrin. That’s our man: schlub Gatsby, nerd Gatsby, middle-management Gatsby. And that’s Gatz in a nutshell, returning Gatsby to earth, respectfully uncovering the text’s rich absurdities, and getting at the inherently threadbare nature of even the greatest and grandest American excesses. “He was a son of God — a phrase which, if it means anything, means just that,” reads Shepherd/Nick, and at that, he halts, five hours in, for the first time in the show. He rereads the sentence. He pauses, thinks it over. Then he gives up, defeated by the tautology, and moves on. This exquisite little moment deepens Fitzgerald’s old riddle about the vacuum at the center of American lives, stages a collision of theater and prose, and plays as a perfect gag. Then the sixth hour begins, we can see the pages dwindling in Nick’s hand, and, oddly for a bunch of people who’ve been cooped up inside a theater all day, we want nothing more than to be borne back ceaselessly into the past, so we can experience it all over again.

At the Public Theater through November 28, 2010.