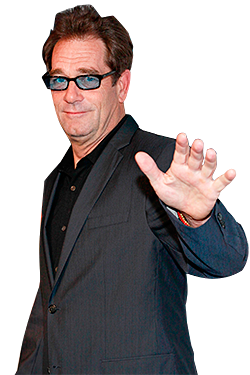

Along with his homeboys the News, Huey Lewis has been dormant since 2001’s Plan B. But now Huey Lewis is back! A few weeks ago, the band released Soulville, a Stax cover album that features Huey’s vocal takes on classic cuts from the likes of Solomon Burke, the Staple Singers, and Joe Tex. Vulture recently got Lewis on the phone to talk about musical influences, Detroit vs. Memphis, and, of course, Back to the Future.

What about soul music resonates with you?

Originally my dad was a big band jazz drummer, who played Bennie Goodman, Basie, and Ellington around the house a lot. He didn’t like singers very much, mostly just big band jazz stuff. And my mom oddly enough, was a bohemian artist-type and got right into the psychedelic stuff. So I think it was the one kind of music available to me that my parents didn’t like. It was my way of rebelling, if you will.

How’d you end up focusing on Stax?

We didn’t strictly, to be honest. The Pickett songs, for example, were on Atlantic, and the Joe Tex record wasn’t a Stax record. But we wanted it to be that kind of Stax, Memphis music, as opposed to Motown. Things are completely different, and it’s not for everybody, this music. It’s fairly primitive and raw. It’s the way I’ve always liked it.

So why the Memphis stuff over the Detroit stuff?

The Motown stuff was great, but for some reason it was a little too much for me. I didn’t like the strings. The Stax stuff, it’s so primal. And I think the appealing part is the singer is out there more and it’s about the commitment. The guy sings whatever it is he’s singing, and you believe it. He’s not faking, it was urgent and primal. I started out as a blues harmonica player, and it’s the same thing. It’s a commitment thing. There’s something about those singers that says, “We’re not kidding, this is life or death.”

Which songs on the album stick out to you the most?

One that was important is the Otis Redding tune, “Just One More Day.” If you’re going to do a tribute to that period, you got to do an Otis Redding track. We chose a song that not everyone knows, and it seemed perfect. I was frankly more than a little worried that I could pull it off. I mean Otis had an unbelievable voice and personality. But actually what happened, interestingly, we cut everything live, with no fixes or overdubs. And when we listened back it sounded pretty good. It was as if the soul gods said, “It’s okay boys, go ahead. You’re okay.” We were being anointed somehow.

This is the first album you guys have put out in nearly a decade. What made you feel that now was the right time for a new album?

It was a piece of cake, and a fun project. I don’t personally think about the commercial aspect of anything anymore. Fortunately I don’t have to. That’s a fortunate thing. And I try to make my choices all creative.

You guys also reunited with Jim Gaines, the co-producer of Sports. What was it like working with him 25 years later?

It was excellent. The real reason we chose him [for Sports was] the first album didn’t do anything. So at that point, we had the vision, but we obviously needed a hit. There was no Internet, FM radio was already programmed, it was our second album, and if we didn’t have a hit it was see you later. So if anyone was going to draw the line between commercial and credible, we figured it ought to be us. We were no spring chickens to begin with, we’d been in a few studios, Mutt Lange had produced a couple of records. So we convinced the record company, my manager went to bat for us, that we could do it ourselves. So we needed an engineer and we had tried Jim Gaines previously. And Gaines was just a funky Stax guy, and I love that. He’s just a laid-back country guy. So I said, “Let’s get Gaines in.” At the moment he had quit the music business after making a Steve Miller record.He’d been demoing and said screw it and moved to Oregon, where he was repairing windshields. So I literally got him back in the business to do it. Then we made Picture This and Sports. I let him go and he went on to produce Journey, Santana, and all this other stuff. Then he retired to Memphis, so when we had this idea, because he’s from there and he was originally a Stax manager, we said, “We’ll just get Jimmy.”

We can’t let you go without talking about Back to the Future. How did you originally get involved with the film?

Steven Spielberg told us “We’ve written this film, the character is Marty McFly, and his favorite band is Huey Lewis and the News. How about writing a song for the movie?” I was flattered but didn’t much fancy writing a song called “Back to the Future.” They said, “That’s okay, we don’t need that title, we just need a song.” I said, “Well, I’ll tell you what, I’ll send you the next couple things we send out.” It’s funny because we’re here doing this little reunion, and Zemeckis remembered stuff that I didn’t, which is I guess we sent him this song that wasn’t going to work. It was kind of a minor key thing or something. I hadn’t seen the film yet or read the script. Then he explained to me on the phone, no it’s a real upper and blah blah blah. “Okay so you want something with a major chorus,” he claims I said. I don’t remember that, but he said yeah. So the next thing we wrote was “Power of Love,” and we just sent it down. I was nervous because there’s no overt love interest in the film, and I wasn’t sure it was going to work. They said, “We’re going to come up and hear it.” So he, Bob Gale, and Michael J. Fox flew up and came to the studio, and we played the song for them, and they loved it.