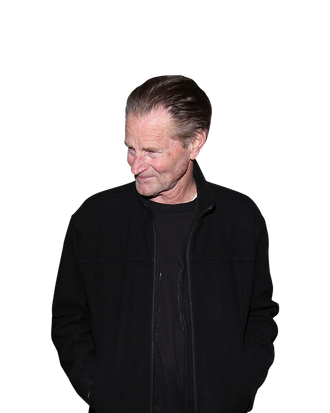

Sam Shepard is calling from somewhere on the road between East Texas and New Orleans. That may sound romantic, but right now heÔÇÖs just trying to make sure the phone line doesnÔÇÖt go dead, and he apologizes in advance for the possibility that it might. The kinds of roads Shepard has charted in his work bear a surprising similarity to the road traversed by his character in the lovely and elegiac new Western Blackthorn, which is one of the highlights of this yearÔÇÖs Tribeca Film Festival. The film marks the welcome return of the actor-playwright-director and all-around Renaissance man as a leading man, playing an aging, grizzled Butch Cassidy hiding out in the mountains of Bolivia under an assumed name. Directed by Mateo Gil (perhaps best known to American moviegoers as the Spanish screenwriter of the Alejandro Amenabar films The Sea Inside and Open Your Eyes), Blackthorn is, like much of ShepardÔÇÖs own work, deceptively complex. Vulture spoke with Shepard about the film, his love of Westerns, and his hidden talent: Singing.

Blackthorn plays on a lot of themes youÔÇÖve explored in your own work. The relationship between fathers and children, for example. Throughout the film, Butch Cassidy is writing a letter to what sounds like the Sundance KidÔÇÖs child.┬áÔǼ

I think thatÔÇÖs one of the things I was attracted to in this film. I loved the script. I really responded to these relationships and to this sense of alienation; it was right along the lines of my interests. This is so different from the original Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. ItÔÇÖs not a buddy movie. ItÔÇÖs really a story of estrangement. ItÔÇÖs about Butch trying to get back home. The guyÔÇÖs really lost out there. Plus, itÔÇÖs interesting, because the kid heÔÇÖs writing to I think might be his own, although he signs [his letters] ÔÇ£uncle.ÔÇØ I liked that innuendo. ItÔÇÖs probably his own child heÔÇÖs writing to. So heÔÇÖs still unable to fully connect.ÔǼ

ÔǬ

Plus, thereÔÇÖs this notion of a character thatÔÇÖs lost out in the wilderness. ItÔÇÖs like an alien landscape out there. You think, Damn, that guyÔÇÖs never gonna get out of there.

Exactly. ThatÔÇÖs good that you got that impression from it; we were shooting for that. That sense of him being very isolated up there.ÔǼ

ÔǬ

You shot much of this film on the Bolivian High Plateau, which sounds like a tough place to shoot.ÔǼ

It was arduous, for sure. The locations were very remote. We were working sometimes at 15,000 feet, and a lot of people got sick because of oxygen deprivation. That certainly geared us up for the movie. The production was threadbare. Plus, there was a language thing going on, too. I speak some Spanish, but not really enough. The director didnÔÇÖt really speak any English, so the screenwriter kind of acted as a go-between. That kind of isolation really helped, actually.ÔǼ

You sing a number of songs on the soundtrack. YouÔÇÖve done music in the past, especially in your early years drumming for the Holy Modal Rounders, but this was the first time I heard you sing. You sound a bit like a young RamblinÔÇÖ Jack Elliott.ÔǼ

Hah! I know RamblinÔÇÖ Jack! [Laughs.] I havenÔÇÖt seen him for years, though. For years, I was afraid to sing, and once I got over it, all of a sudden it opened up this whole other channel for me. IÔÇÖve got a young son, whoÔÇÖs in a band called the Dust Busters. He sings like crazy. We sometimes sing together, and heÔÇÖs got a great voice. IÔÇÖd like to do more singing. It was one of the things that attracted me to this movie, actually, that there was singing involved in the role.ÔǼ

ÔǬ

You also got to act opposite Steven Rea, with whom youÔÇÖve worked with onstage over the years.ÔǼ

ÔǬIt was my suggestion to cast him. I thought he was perfect for that kind of character. I think he really anchors the film. He was fantastic in it. IÔÇÖve known him for a long time. I first worked with him in 1973 in London ÔÇö we did a lot of theater together, before either one of us ever did film.ÔǼ

ÔǬThe Western has been a genre youÔÇÖve been closely identified with. Why do you think we see so fewer Westerns nowadays?ÔǼ

ÔǬI donÔÇÖt really know. I love Westerns. True Grit ÔÇö I think they did a much better job with that than the John Wayne version. And the people that I hang out with still love Westerns. IÔÇÖm a horseman myself, and a lot of horsemen that I hang around, they just adore Westerns as a form. But IÔÇÖm not sure how widespread that is. You know, back in the day when I grew up, the whole country watched Westerns. Hopalong Cassidy and Roy Rogers and The Rifleman. TV was just loaded with Westerns.

ÔǬ

It seems sometimes that foreign directors, like Mateo Gil, understand the Western form better nowadays.

ThatÔÇÖs true. ThatÔÇÖs exactly true. IÔÇÖve worked a lot on Westerns with foreign directors. ThereÔÇÖs one not a lot of people saw, but itÔÇÖs a handy little film called Purgatory that I did some years ago. It was a quirky Western with Randy Quaid and Eric Roberts, and it was done by a German.