Jerusalem is, among many other wonderful things, a feast for the nose. Jez Butterworth’s half-rejectionist, half-heraldic drinking song of a play is perfumed with blood, beer, and badger shit, not to mention Butterworth’s earthy Albionese. Quotation can’t do justice to the confabulated speeches from its crook-backed central figure, the druid-in-chief Johnny “Rooster” Byron (Mark Rylance); his tale about being born of a virgin mother involves adultery, a gunshot to the “love bells,” and a well-timed public tram — and can’t be excerpted with any justice to its musky poesy. But the smell you notice up front is best described as green. It’s the aroma of actual vegetation, trees and grass, growing onstage. (There’s even a live chicken or two, though the birds are mercifully unsniffable.) “Wild garlic and the May blossom” is how Rooster assesses it: The scent whisks us to the woods a boulder’s throw from Stonehenge, where Rooster — a gin-blossomed ex-daredevil who delights and terrorizes the locals with outrageous behavior he terms “rural display” — serves as stumblebum steward of a trailer-park Arden. He sees himself in a long tradition of Britain’s cheerful lords of misrule: Falstaff, Jack-of-Green, Robins Hood and Goodfellow, all shifty garden gods of predation and protection both, who flout the faddish morality of mere mortals and hew closer to natural law. That’s Rooster’s version, anyway. According to local authorities, he’s just another deadbeat drug dealer who supplies speed and liquor to minors and hosts wild midnight bacchanals. But then, as Rooster points out, “What the fuck do you think an English forest is for?”

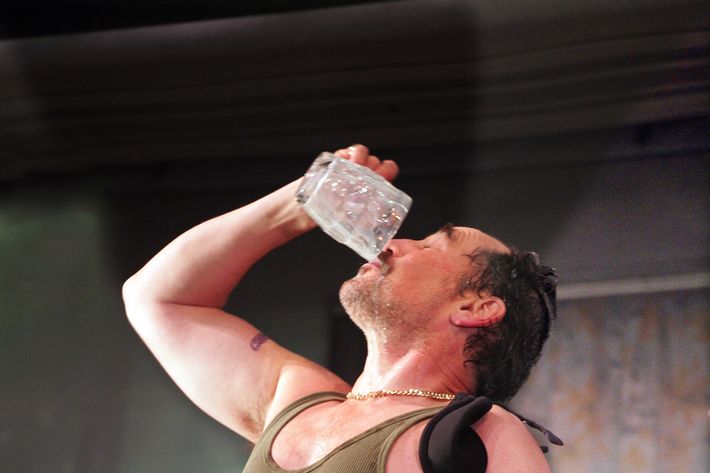

Stumping along in a broken body that looks reconstituted from expired beef jerky and animated solely by gypsy oaths and crank, Rylance’s Rooster is a (barely) walking reply to consumerism and conformity. He’s merry without being happy; beneath his roars of protest, he knows his England will always deny him, always fail him. Butterworth, communing with the spirit of William Blake, can’t help overromanticizing his hero-monster. Past a certain point, the playwright simply refuses to push Rooster any deeper into the moral bracken. (Coiled in the grass is a smoldering subplot about a missing runaway and what Rooster may or may not have done with her.) In the end, this isn’t really Fagin or Falstaff we’re dealing with. Occasionally, Robin Williams seems a closer relative than Robin Hood.

Rylance, renowned for his use of buffoonery as a martial art, refuses to ask for our love, nor for that of his onstage fellows. The supporting characters here never get close to the real action, even when they’ve been lavished with stage time. Most of them are mere accent pieces. (And speaking of accents: Some are more stable than others, as the Yank actors — added since the transfer from the West End — struggle with the gummy Wessex dialect.) Only the glorious bag-of-bones Mackenzie Crook, playing an aging forever-hometown boy in a tragic hoodie, even gets close to getting close to Rylance’s Rooster. But even he can’t hold Rylance’s eye line for long. He knows the local kids simply use him for amusement. He seems to intuit his future: Hal threw Falstaff under the bus, and his fate will be that of all the great, green-gilled gormandizers of the realm. And so, setting himself boldly and a little coldly apart from his fellows, and from his audience, Rylance remains impertinent, impenitent, and impenetrable to the last, adding another savage clown to his gallery.

Is Jerusalem expressing more than mere discontent with a modernity we all agree is thoroughly depressing? That’s unclear. But the show is testament to the ever-expanding voice and vision of Butterworth, whose mighty verbal broadsword just freakin’ sings. Having loosened his belt since the dominance games of The Winterling and his 1995 breakthrough, Mojo, he’s now written the chav equivalent of a great, sprawling August Wilson mystic incantation. As a play, Jerusalem may be merely impressive; as a rite, as “a rural display,” it’s a bona fide bustle in your hedgerow and not to be missed.