The American Folk Art Museum is abandoning its building on 53rd Street and retreating to its old Lincoln Center cubicle. My colleague Jerry Saltz knows exactly whom to blame: the architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, and the critics who enabled their ÔÇ£utter lack of imagination and hubristic mess of starchitectural vanity.ÔÇØ Jerry and I discussed this building once before (in a portion of this conversation that was edited out), and so with his enthusiastic assent ÔÇö ÔÇ£Bring on the pain!ÔÇØ he e-mailed, when I offered to argue with him in print ÔÇö I pick up our spirited debate again.

LetÔÇÖs start with the obvious: In order to construct the building that opened in 2001, the museum crippled itself with $32 million in debt and has defaulted on the loan. ThatÔÇÖs not an architectural misdeed; itÔÇÖs terrible fiscal stewardship. Blaming the designers is like faulting Mercedes-Benz for making such lovely cars that minimum-wage workers go bankrupt buying them.

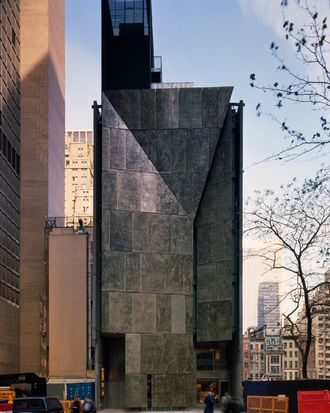

Jerry hates the exterior with such passion that he produces the old ÔÇ£Kleenex boxÔÇØ simile that others have regularly lavished on the vainest starchitect of them all, Frank Gehry. More cruelly still, he compares it to a ÔÇ£miniature suburban professional building,ÔÇØ a phrase that to my mind brings up something more like this. I have always found the Folk Art MuseumÔÇÖs facade an alluring exception to the tough sleekness of midtown (and of the Museum of Modern Art down the block). The folded metallic panels have a textured, tactile, handmade feel, just like much of the art inside.

The odious term ÔÇ£starchitectureÔÇØ gives the impression that Williams and TsienÔÇÖs design self-indulgently overwhelms the contents. Hardly: The little museum that couldnÔÇÖt was largely made inconsequential by the presence of MoMA, which is gobbling up the entire block and monopolizing attention. What tourist or art-world regular, emerging from four hours spent wandering among Pollocks and Picassos, has the fortitude to say: ÔÇ£Hey, why donÔÇÖt we duck into that cute little Folk Art Museum next door?ÔÇØ

JerryÔÇÖs critique of the interiors is potentially more damning, but his objections focus mostly on the paucity of horizontal space and the profusion of staircases. I understand those frustrations, but in midtown Manhattan, 30,000 square feet of broad, open galleries represent an imperial scale of luxury. MoMA can afford that; the Folk Art Museum never could, which is why it bought a small lot and asked its architects for a vertical museum. Williams and Tsien created not just one up-and-down, take-it-or-leave-it pathway, but a set of vertical itineraries that rise toward the sun filtering through the skylight at the top. The architects didnÔÇÖt just do the best they could; they did far more than anyone had a right to expect.

But no architectural finesse can compensate for inadequate management, overreach, poor timing, or bad luck. The American Folk Art Museum ÔÇö like New York City Opera, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and arts institutions around the country ÔÇö has found that a bad economy is unforgiving and that the wages of fiscal imprudence are drastic artistic sacrifices. Misfortune doesnÔÇÖt strike evenly. Even as the Whitney starts construction on its new headquarters, the Met plans to annex the old Whitney, and MoMA keeps desperately trying to satisfy its cravings for more space, Jerry foresees a period in which museums start tearing down the products of their own building binges, and he may be right. But blaming Williams and Tsien, or their lovely little building, for a nationwide epidemic of museum obesity amounts to clubbing an innocent bystander.