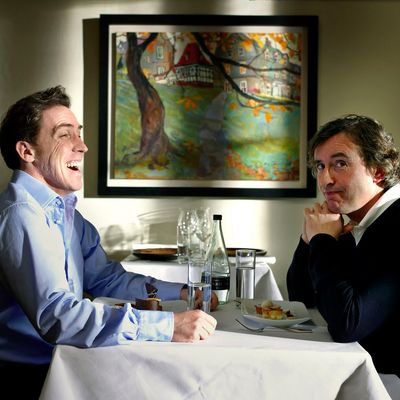

The deadpan, sporadically funny road movie The Trip is the newest chapter in the saga of British director Michael Winterbottom, and his frequent leading man, Steve Coogan, attempting to get mileage out of ridiculing Coogan’s narcissistic on-screen persona. Winterbottom cut the movie together from a six-episode, semi-improvised BBC2 series, the premise of which is that Coogan, commissioned to act as food critic by the Observer newspaper, and actor Rob Brydon, allegedly the last choice among his mates for a traveling companion, embark on a voyage to the north of England to sample the fare at various high-end restaurants. Over several days, doleful Coogan and chipper, long-faced Brydon banter, mock-insult each other (or is it so mock?), recite Wordsworth and Coleridge, and compete to do the best imitations of sundry movie stars, among them Michael Caine, Sean Connery, Liam Neeson, Al Pacino, Hugh Grant, Anthony Hopkins, Roger Moore, and Woody Allen. The film would be rather a slog without those dueling impressions. With them, there’s at least one thing to look forward to around the next bend.

You can actually watch the best part of The Trip on YouTube: Coogan and Brydon’s Michael-Caine-Off. The great impressionists — Brydon and Coogan both qualify — hear more deeply than you and I do. They don’t just understand the physiognomy of their subjects—where the sound comes from and how it makes its way from the diaphragm to the larynx through the nose and throat, etc. They also get into their subjects’ heads and convey the thinking, perhaps even the worldview, underlying that verbal attack. You listen to Coogan and Brydon’s Anthony Hopkins and hear a combative cadence you’ve never fully recognized — a rhythm that make Hopkins so “forceful” but also, once you slice through the ham, a little boring. It’s too bad that Coogan and Brydon don’t do as well with Americans, who remain alien entities. In general, Brits aren’t as attuned as Canadians and Aussies to nuances of Yank speech.

Winterbottom’s and Coogan’s larger agenda is to reveal the tragedy of “Coogan’s” life. His first choice of travel companion, his girlfriend, Mischa (Margo Stilley), helped plan the itinerary and then bowed out when the relationship hit a rough patch from which it’s unlikely to recover. Coogan trudges around the Yorkshire moors searching for places to get a cell phone signal — then stands in the fog and cold having foggy, cold conversations with Mischa, unable to tell her that he cares enough to try to turn things around. His other calls are from a Hollywood agent who assures him that the Coogan brand is still potent, even though the actor has had little luck breaking through in American movies. He sulks when the Northerners don’t recognize him — and even more so when they recognize Brydon, well known for his Little Man in a Box bit in which he makes his voice uncannily tiny and muffled. Coogan gets a revenge of sorts by sleeping with women along the way, although he’s sadder than ever in the morning, when his conquests have slipped away and he’s once more with Brydon, who has a wife and children waiting for him at home. (Brydon’s relationship with his wife has its own peculiarities, as he keeps slipping into celebrity voices on the phone — he can’t seem to find his own.)

The meals are supposedly the point of the trip, and Winterbottom shoots them with rigorous irony, cutting back and forth between the artisans in the kitchen carefully composing their vertical plates (it’s all exquisite piles and foams) and the diners receiving each course (say, a duck-fat spiced popcorn lolly) with a mixture of awe and irreverence. (“It has a consistency like snot but it tastes great.”) Winterbottom doesn’t seem especially interested in the food per se, only in the contrast between its fussy presentation and the weathered, ancient landscape. (Coogan and Brydon eat more scallops than anything — not exactly native Yorkshire fare.)

Winterbottom’s subjects express even less interest in those landscapes than they do in the food. (One of the funniest bits is Coogan’s agonizing retreat from a fellow hiker discoursing at great length on the rocks and glacial origins of a particular set of cliffs.) Travel doesn’t broaden or liberate them: The trip only brings home the pettiness and misery of their lives. It doesn’t bring them closer, either. A climax of sorts is when each composes a withering funeral oration for the other. The key influence on the final scene (Coogan staring out the window of his lonely apartment) is Local Hero, one of the loveliest travel comedies ever made. But, in that film, director Bill Forsyth showed a man truly touched and potentially transformed by another culture — even if the people in that culture were primarily interested in him as a means of escaping their poverty. Coogan hasn’t been touched by anyone or anything. His misery endures.

The Trip has a lot of good, wry moments, but it’s repetitive (maybe it works better in six parts on TV), and the bad vibes wear you down. When Albert Brooks in his classic Lost in America (the other great road comedy of the eighties) took to the highway to demonstrate his alter-ego’s inability to escape his own ego, there was an expansive spirit at the center: Here was a deluded narcissist who longed to be bigger, finer, more open. The center of The Trip is curdled. Hence the dead end.