Carey Mulligan is an actress of consummate control, making her a not-obvious choice to play Karin, the God-haunted schizophrenic at the center of Ingmar Bergman’s 1961 Through a Glass Darkly. Bergman’s ghostly meditation on faith and madness has been given a smart, firm, yet occasionally flat-footed adaptation at the hands of Jenny Worton, and directed with not-always-admirable restraint by David Leveaux. At the play’s depressingly stable center is another impressive performance from the wildly talented Mulligan, whose broken naïf Nina in The Seagull still exists, in afterimage, on the back wall of my mind. Her Karin, however, is another animal entirely — whereas Nina is a victim, Karin is psychonaut, a dauntless explorer of the soul’s outer-skerries, using the rubble of her wrecked life as stepping stones to the Divine. She’s also a plain old mentally ill young woman, on a beach reprieve from the asylum, caught between the four men in her life: her overbearingly solicitous husband, the man-of-science Martin (Jason Butler Harner); her chilly author-artist father, David (Chris Sarandon, adding to a career-long roster of cold fish); her angry, hormonal, Oedipally inclined teenage brother Max (Ben Rosenfield — good, but too old to be truly effective in the role); and a whispered God who beckons her from the other side of the wallpaper. What will Karin choose to believe? Does she even have a choice? Do we?

Leveaux re-creates Bergen’s high-latitude light and stages Karin’s episodes with classy pseudo-cinematic touches. (I especially liked the scrim he hangs between the main action and fissured wall in the unfinished room where, Karin feels sure, He is waiting, just out of sight.) And Worton has a crystalline ear for hypnotic dialogue. (“We spend our whole lives turning our faces away and then on holiday we have all this time to look straight ahead and stare into the abyss,” says Karin. “If you could touch a holiday, you’d put your hand straight through it.”) But neither of the show’s principal creators has an excellent grasp of Bergman’s technique of creating existential terror with empty space. Not that slavishly re-creating an auteur’s work onstage should be a director/adapter/dramaturg’s primary concern, of course — but this particular adaptation feels far more scientific and psychically remote than its source, which was, after all, conceived as an intimate chamber piece, a bedroom exorcism. (Takeshi Kata’s cavernous, barnlike, schematized beach house set feels, I’m afraid, like an abandoned Wal-Mart.) David, as superciliously embodied by Sarandon, has almost no vulnerability at all — he’s accessed all of the character’s predatory qualities but little of his skulking voyeurism and cowardice, making his implied culpability in Karin’s illness and Max’s confusion much too easy to accept and dismiss. And even Mulligan’s Karin doesn’t quite touch us the way she should: She’s plenty convincing, yet we feel her convincing us. There’s rarely much danger onstage, and this house never feels quite as haunted as it should. I sat and appreciated, and sometimes even marveled at, Through a Glass Darkly for 90 minutes, but waited in vain to see someone — Leveaux, Mulligan, or both — take her hands off the wheel, cover her eyes, and floor it.

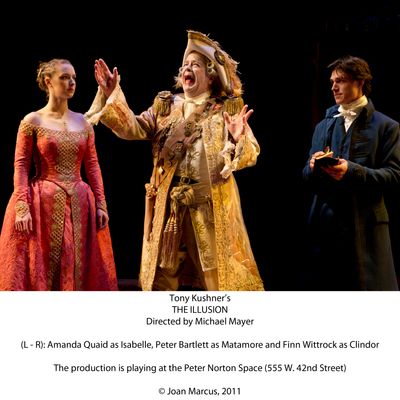

Across town, another waking dream is unfolding: Tony Kushner’s The Illusion, his 1990 refurbishment of Pierre Corneille’s L’Illusion Comique, is closing out the Signature’s Kushner season. Corneille’s seventeenth-century mise-en-abyme puts modern ironists and meta-mongers to shame with its devious matryoshka doll structure and self-annotating, genre-bending, tragicomic manipulations: Starting with a framing story about a once tyrannical, now repentant father, Pridamant (David Margulies), pleading with the cave-dwelling sorcerer Alcaldre (Lois Smith) to conjure images of his estranged son (Finn Wittrock), The Illusion quickly plunges into a maze of mirrors. As Pridamant watches his son’s life play out — first as comedy, then as romance, finally as tragedy — names keep changing, lovers revolve in and out, and his prodigal offspring proves himself a shifty character indeed, “an unholy freak of nature, outlandishly amalgamated, a veritable hippogriff.” (Kushner, a seasoned verse playwright himself, digs into the language with his customary delight.) He pings between the noble and naive Melibea/Isabelle (Amanda Quaid) and the sadder-but-wiser Elicia/Lyse (an excellent Merrit Wever), her canny servingwoman. (As Matamore, an intruding pantaloon just-in-from-the-commedia-dell’arte-and-boy-aren’t-his-gags-tired, the indefatigable Peter Bartlett nearly overturns the show more than once.) Mediating all of this is the artist-emcee Alcaldre, whom Smith reinvents as the sort of plenty-earthy, not-exactly-motherly earth-mother she’s become rightly renowned for playing, and her sometimes-tongueless assistant, the Amanuensis (Henry Stram), who’s eventually forced into service as one of Alcaldre’s illusions. Love and art are vicious, Kushner and Corneille are telling us, and director Michael Mayer underlines this with playful scene work, color schemes, and sets that evoke a bloody, bawdy graphic-novel — sometimes, the show appears to have been illustrated by Charles Vess. The themes on offer are in some ways similar to those of Through a Glass Darkly, but these visions are as lurid as Leveaux’s are etiolated. These illusions aren’t meant to be terribly convincing, and, occasionally, that’s a problem: Broad, presentational acting runs the risk of setting audiences adrift, and by the time Stram arrives, transformed into Isabelle’s pitiless father Geronte, we’ve gotten so used to the mirage, we’ve forgotten it can be solid. Stram brings us back to earth, rather brutally actually, and death finally comes to the garden — only to be banished with a quip. All’s fair, it seems, in love and theater. There were still a few rattles in the old god machine during the preview I saw, and I suspect the play’s colors will deepen as its run progresses. Like any good illusion, be it a love affair or a light entertainment, this one will improve with practice.

Through a Glass Darkly is playing at New York Theater Workshop through July 3.

The Illusion is playing at The Signature Theatre’s Peter Norton Space through July 17.