Guest blogger and screenwriter Brian McGreevy is upset about the post-Twilight emasculation of vampires and is currently professionally working to re-masculate them: He is adapting Bram Stoker’s Dracula for Warner Bros. and Leonardo DiCaprio. Additionally, his vampire-themed novel Hemlock Grove is coming out in winter 2012 from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, and he is working on the film adaptation with director Eli Roth.

The old-fashioned, iconic vampire is in many ways the ideal man. Let’s call him the Romantic vampire, famously modeled on Lord Byron and best associated with Bram Stoker’s Dracula later in the century. (As opposed to the traditional vampire from Slavic folklore, a dumb and socially ungraceful specimen of peasant stock that more closely resembles the present-day zombie and whose origins could be found in plague anxiety and an impressive misgrasp of forensic science.) The Romantic vampire is a real customer, with looks, charm, style, wealth, and insatiable demonic appetite. Imagine the first bite of a perfectly seared piece of meat — to him you are that meat. Eros and Thanatos join forces in this vampire; no one else can make a woman feel this wanted or alive (for the moment).

But over the last decade, something has gone terribly wrong with the modern vampire. Take the biggest offender, Twilight. Granted there is an inescapable genius to its command of 14-year-old girl psychology; its premise is that the hot, broken guy who breaks into your house to draw you while you sleep wants to wait until marriage until he nearly screws you to death on a feather bed. Probably Stephenie Meyer’s major contribution to the vampire canon is one of her most derided: Her vampires sparkle in sunlight. But the sparkling is hot stuff; if Keith Richards were undead, he’d absolutely sparkle, and the most objectionable thing about it is setting a standard of legitimate hotness that is otherwise unmet by the series. And True Blood, meanwhile, is essentially what you would get if a Tennessee Williams play fucked The Rocky Horror Show Picture Show. Even the most vehement apologists can make no defensible argument that it’s objectively good — the great achievement of the series seems to be how mind-bogglingly, decadently not good it is. And while these two examples provide wildly disparate takes on the vampire mythology (or, at least, different levels of irony), they share two notable elements: a young female protagonist, and a vampire love interest who does not even try to eat her. Much has been made of the damage inflicted by the “male gaze” in film, but what of the female gaze? It’s taken the Romantic vampire and cut off his balls, leaving a pallid emo pansy with the gaseous pretentiousness of a perfume commercial. We are now left with the Castrati vampire: This is pornography for tweens, as well as a worrying reflection of our time.

Just as the Frito-Lay Company has created virtually nutrient-free vehicles of corn syrup and salt that make our youth fat, slow, and indiscriminate, the Castrati vampire is a confection that has the same impact on the psycho-dramatic imagination of today’s youth. Think of the message here: What is the consequence of falling in with a Romantic vampire? Death, either yours or his. What is the consequence of falling in with the Castrati vampire? Long and torturous (at least to everyone around you) conversations about feelings. This is not what really happens when you fall in with attractive monsters.

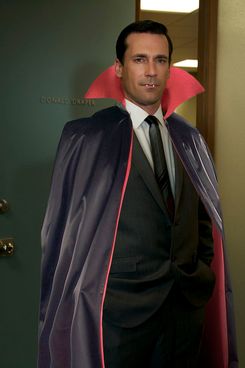

And yet, though the Romantic vampire is an endangered species, I am pleased to report it is not yet down for the count: Hiding in plain sight there is a worthy and culturally significant keeper of the flame. This existentially tormented soul has emerged from death in the guise of an ideal man, a sartorially gifted aristocrat with more mystery and poetry and primal magnetism in one fingernail than 50 Edwards or Bills. And, as it is depicted time and again with unflinching candor, falling in with this demon will inevitably yield destruction: It is you or him. Of course I refer to Don Draper on the AMC series Mad Men, the purist’s vampire of choice for our time. This one has teeth. And adding an extra layer to the mystique is his position as an advertising executive. A more elegant embodiment of the metaphor could hardly be asked for: He is an engine of want, creating the illusion of fulfillment while sucking you dry. No is not in his vocabulary. Neither is yes — yes is implicit. He knows this, he is past needing to hear you say it. He knows the private and unmentionable place that cries “yes” when the bottom drops out of an amusement park ride and suddenly you are in free fall, and, like the ideal man, he is listening.

When Mad Men first premiered, much of its appeal was attributed to novelty factor: What a different time it was, when the American male was an unrecognizable breed of scandalous, id-driven malefactor; heedless, rapacious, just waiting to slide off his doe-eyed secretary’s pencil skirt and show off his executive account. But novelty doesn’t sustain four years of cultural obsession and fascination. Modern conventions notwithstanding, the only possible explanation for the show’s continuing impact (not to mention Don Draper’s appeal to the exact demographic that should find him the most repugnant — modern women) is not what it’s saying about fashion, but what it’s saying about nature. The only thing that has changed is permission to openly admit how unbearably hot his behavior is. Granted, along with the vampire’s emasculation, it’s no secret that this is a silly time to be a man in America. It doesn’t raise an eyebrow these days to find him in jeans cut for the opposite sex (presumably to showcase how ladylike and ill-equipped those legs are for a sudden large predator attack or invasion of an enemy force), or carrying around his young in a baby carrier around his abdomen less like a female of our own taxonomy than a marsupial. Appalling. Also, a lie. Men are predators at heart. Any refutation of this is also a refutation of evolution, or the common sense conclusion of observing a typical 3-year-old boy at unstructured play, his wake of destruction the envy of a Visigoth. It is a killer’s heart that is the motive force of masculinity and predation its spirit. This is not to suggest nature is immutable, or that one ought to act in blind obeisance to it, but that “ought” is not in the vocabulary of want, and choosing is meant to have consequences.

Therein is the point of the unfixed vampire, just as it is with Draper: He is a bridge. On one side, a Locke-ian avatar who not only participates in the social contract but does so like a total pimp. At a dinner party, you pray you will be seated next to him — of course you want to be next to him. Nothing he wears is off the rack and he has the wittiest but not monopolistic anecdotes and most thoughtful gaze as if even though you just met him and it’s so funny you’re even talking about it he’s genuinely invested in that weird dream you had last night and just sitting here he is fucking killing it. Because not only is he the most magnetic and urbane person in the room, but you know that underneath it all he’s just waiting to get you alone and rip you apart with his teeth. This is the other side: a dark, hungry Hobbes-ian id machine, an ancient and unruly beast that only wants to fuck and feed and in his enthusiasm confuses the two. And this bridge is us; forget this at your own peril. Or, in the words of Roger Sterling: “We drink because it’s what men do.”