When is a revival less dated than the day it opened? When it is Rent, Jonathan Larson’s rock-musical retelling of La Bohème, now bonsai’d to Off Broadway dimensions and playing at New World Stages — once a half-price second-run cinemaplex, now a three-quarter-price second-run theaterplex. (Neighbor shows include Avenue Q and the soon-to-open Million Dollar Quartet, both fun-size if not exactly fun-priced: Orchestra seats are still $85 and up, and “premium” seats — whatever those are — run up to $175.)

Rent’s vision of New York City (and, by extension, “America at the end of the millennium”) is unmistakably late-Reagan, with hints of early Giuliani: AIDS, heroin, tent cities, street crime, and starving artists living hand to mouth in Alphabet City in unheated lofts that are still unaffectedly industrial. Larson began work on the show in 1989; when it opened in 1996 and instantly became the college theater-geek equivalent of a Pulp Fiction poster, Rent was already an artifact. By the late nineties, the East Village was functionally closed to any young artist without a trust fund, and the lives of creative types in the big, dirty city were already being defined less by disease and drugs and blight, and more by merit badges of hipness: bands name-checked, Zeitgeist novels referenced, old movies and TV shows nodded to. Rent, compared to the increasingly ironic world around it, was painfully sincere, and that’s probably why it succeeded. There’s only us / There’s only this / Forget regret / Or life is yours to miss. Who doesn’t need to hear that every once in awhile, especially if it’s borne on the back of a majestic anthem?

Rent may be made of cheese, but that doesn’t make its score any less tremendous or gratifying. There’s something fresh and urgent and involving in just about every single number. Sure, the textures and orchestrations feel a little dated; same goes for Hair, same goes for Company. But what, in ’96, felt like forgivable Broadway jet lag (pop musicals being, on average, ten to fifteen years behind actual pop music) now comes across as cutting-edge eighties nostalgia. And not a moment too soon: In case you haven’t noticed, it’s not a bad time to revisit urban fantasies backgrounded by economic collapse, opportunistic right-wing rapine masquerading as “austerity,” and the wholesale abandonment of an entire generation. The tent cities may be razed for farmers’ markets and the drug cocktails may be keeping the virus at bay, but if you’re looking for picturesque (or not-so-picturesque) social de-cohesion, it’s likely just a flash riot away. There’s still plenty of darkness to raise a song against.

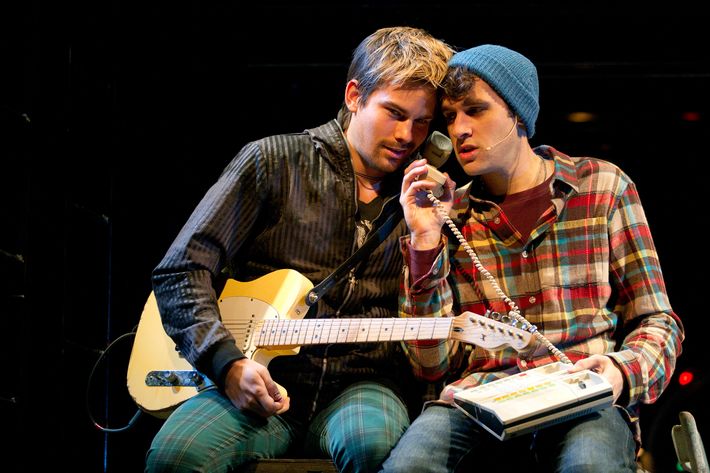

Aw, who am I kidding? It’s freakin’ Rent! Not Angels in America! Though there is an ethereal drag-queen named Angel (reinvented for the Age of Gaga by the silky MJ Rodriguez) and everyone rattles on quite a bit about America. Our camera-toting Virgil, Mark (Next to Normal’s Adam Chanler-Berat), has lost his Harry Potter scarf and his trademark hipster glasses, but retains his slightly plastic passion. A highly athletic Mimi (the startlingly beautiful Arianda Fernandez) swings around Mark Wendland’s dense tenement jungle-gym set like a lemur; she’s a searing stage presence, even when she can’t negotiate all of her notes. Her beloved, tortured rocker Roger (Matt Shingledecker) has a similarly slippery relationship with pitch, and their relationship, designed as the romantic heart of the show, doesn’t resonate. Shingledecker, especially, feels slightly miscast — torture, for him, seems as foreign as Gitmo. You can’t see him on a street corner; he’s so clearly a creature of Foursquare, radiating prosperity and complacency and entitlement. All of which may accurately describe the target audience of Rent, but which cannot, under any circumstances, be allowed to pollute the show’s snow globe of wintry angst. Otherwise, the whole thing shatters.

Luckily, Rent is like a sea sponge: It can live without a single heart because it’s got a thousand little chambers, each of them suffused with musical pleasures and gift-wrapped performances. It’s not a show; it’s a colony. Among its most distinguished residents: Annaleigh Ashford’s Maureen — a daffy AC/DC performance artist and the kind of bed-hopping bi-girl who set loins aflame in the nineties — is a wonder to behold. Ashford, whose comic timing is as tight as her diamond-cut voice, looks like she’s vying to be the next Kristen Chenoweth, and there’s every indication she’ll succeed. She’s well-matched with Corbin Reid’s smoldering Joanne (a part that usually ends up on the dowdy side of Butch Mountain), who matches her flubbery inamorata note for note and step for step. Nicholas Christopher’s Collins — a part originated by that ebullient papi Jesse Martin — is a quieter, more contemplative sort, a retiring, romantically starved MIT nerd who just happens to be a black gay anarchist. (Just typing that sentence makes me realize why I love Rent: Its character-loglines, like its themes and dreams, are so sweetly, unapologetically ridiculous.) His relationship with Rodriguez’s more poised, more androgynous, more fashion-plate-y Angel takes on a refreshing new vibe when it’s less clear who wears the pants.

So: Will you miss the old Rent crew, most of whom have gone on to relative superstardom? Sometimes you do, most of the time you don’t. The producers made much of their YouTube-ish open casting call, and all of the young stars who made the cut do have a touch of the Glee generation in them — some, more than a touch. Their voices, individually, are solid enough, but don’t compete with their forebears. There are weaknesses and bald patches here and there, and there’s clearly been a general brief to stress the interior over the presentational in all things, vocal projection included. But the choruses are hauntingly beautiful and often ravishing in their power and purity. After all, the real star of Rent is now and has always been Larson, whose often transcendent pop score (and yes, it’s pop, not “rock,” let’s be clear) holds up remarkably well. What you may miss, if you’re a starving student, are the subsidized front-row seats that helped make the show a youth sensation, despite all economic headwinds. Today … $85? Too damn high!