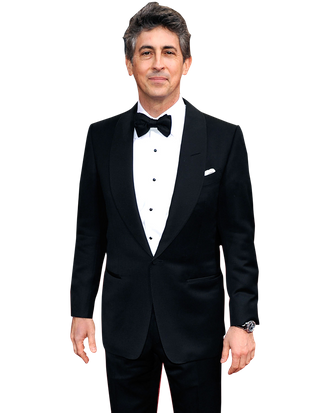

Alexander PayneÔÇÖs The Descendants, which hits Blu-ray and DVD this week, just won him his second Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay (heÔÇÖd also won for his previous film Sideways), cementing his status as one of AmericaÔÇÖs most reliable adapters of literature. But in many ways that status is a bit misleading, because it has been PayneÔÇÖs sensitive yet understated directing style that has truly brought these stories to life. Either way, though, with an unbroken string of acclaimed films under his belt, Payne is now one of our most consistent popular artists. He spoke to Vulture recently about his cinematic influences and the nature of adapting a novel.

One thing IÔÇÖve noticed in almost all your films: You seem to do monotony very well. Your characters when we first meet them always seem to be treading water, living somewhat unremarkable lives. And yet you somehow manage to make that cinematic. How do you pull that off?

Next question! [Laughs] I have no idea. Sorry, IÔÇÖm not trying to be disingenuous or John Fordish with that answer. I donÔÇÖt know. I just write and cast and direct and edit and hope it all works out. I guess maybe I try to make movies that are closer to real life than are many Hollywood movies. But I still try to stay within a commercial narrative, a contemporary American vernacular. And yet to have some resemblance to the rhythms of real life.

But at the same time youÔÇÖre able to introduce elements of broad comedy into these films, without necessarily disrupting their very human tone. It reminds me a bit of Italian cinema, of these very humanistic comedy directors like Pietro Germi and Ettore Scola.

Well, IÔÇÖll take that as a compliment, because IÔÇÖm a great fan of Italian cinema of the fifties and sixties. And Scola, as you know, was a screenwriter as well for many other great Italian directors. I seek a lot of inspiration from those films. I always wanted Sideways to be like a great 1960s Italian film. It was influenced in part by Il Sorpasso, by Dino Risi. I like in those films just what youÔÇÖre saying ÔÇö that rich, rich sense of humanity, and a warm sense of the absurdity of life underneath all the proceedings.

In some ways, The Descendants brings into sharper relief your journey as a filmmaker: ThereÔÇÖs been a progression from nihilistic satire towards something more optimistic.

Well, I still reserve the right to be pessimistic and sarcastic and nihilistic. [Laughs] Maybe what youÔÇÖre seeing as a progression is more my being able to survey more of American life ÔÇö or the world I see around me as I get older ÔÇö as I develop a more confident film technique. But IÔÇÖll be honest with you, IÔÇÖm also really dying to make a straight comedy again.

What was the hardest part of adapting The Descendants? Was there anything that was tough to discard?

Nothing was hard to discard. IÔÇÖm happy to discard things, and pluck out that which I think is directable, that which I personally can already relate to, or relate to in an interesting way. But some of the challenge of this adaptation was stretching the narrative to something that could be cinema. ItÔÇÖs a very internal novel. There werenÔÇÖt a lot of showy incidents that were going to automatically translate to a great movie scene. I had to take this very calm prose and yank it into cinematic narrative. That took some thought. But all that said, itÔÇÖs an extremely faithful adaptation to the book.

But in the past you have discarded large chunks of your source material. Famously, About Schmidt bears very little resemblance to Louis BegleyÔÇÖs novel.

Oh yeah. Well, that movie was very sui generis. The more I worked on that story, the more I wound up discarding the book and then going back and revising a previous script of mine, which was the first script IÔÇÖd written straight out of film school. So then what I did was I basically stole a couple of ideas from Mr. BegleyÔÇÖs book to help me get out of some narrative problems. Now, that was a very unique case, but itÔÇÖs also a fact that I could only ever get involved with an adaptation where I had complete freedom to change as much as I need to or want to. I could never do a Da Vinci Code or a Harry Potter movie, where you have a loyal fan base that essentially wants to see a filmed book on tape. I would be hard-pressed to do that. I think, like Stanley Kubrick, a director has to assume a rich dialogue with the source material, so that by the end of the process both the source material and the directorÔÇÖs voice are served.

Speaking of changing things, have you seen the Japanese adaptation of Sideways?

Oh, God, itÔÇÖs unwatchable. I watched the first 25 minutes, and thought, ÔÇ£Are they kidding?ÔÇØ But I made some money off it, so I canÔÇÖt complain too much.

Have you been following the contraception and abortion debate going on in the news? ItÔÇÖs totally absurd. I keep thinking it could be something out of Citizen Ruth.

All I know is, the Republicans are digging their own stupid grave. And the Democrats are just gleeful. ÔÇ£Oh, you want to bring up abortion and contraception? Please, go ahead!ÔÇØ There was just an article in the Sunday Times about that, about how Obama has to seize on that. But you know, Citizen Ruth was more an anti-politicization movie. It assaulted everyone, on both sides. But yeah, this whole thing is totally absurd.