Other girls loved Paul McCartney or John Lennon, but when I was in high school, I loved Hilton Kramer.┬á Kramer ÔÇö who died today at age 84 ÔÇö was, of course, the art critic of the New York Times, and one of the few critics in the (relatively short) history of art criticism to command a national reputation. His prose was crystalline and conveyed a deep knowledge of modern art,┬á not to mention a propensity for outrage that seemed in keeping with the inflamed tone of sixties dissent.┬á His detractors dismissed him as a grump and an ideologue, and in later years he was both. But he did, in truth, achieve something genuine: He infused American journalism with a sense that contemporary art matters hugely, and he brought everyone into the debate.

He hated Andy Warhol and couldnÔÇÖt forgive him for being so popular. His loyalties were with the modern movement, Picasso & Company, about whom he wrote volumes upon volumes of graceful, literate prose. Yet he seems destined to be remembered for his poison darts, for which the sixties art world provided endless targets. If a work of new art was popular, it was, in his mind, flawed, a piece of defective engineering, missing an essential part, the part that made it a work of art and not a psychedelic poster. He believed in strict boundaries, in immutable divisions; that art was either good or bad, abstract or figurative, high or low, painting or sculpture. In this sense he represents values that have come to seem too fixed and arbitrary to hold much sway today, where the best line is a blurred line and the best artists are mix-masters who understand that the concept of purity doesnÔÇÖt even work in the Bible.

I first met Hilton in 1987, at a press preview for the Frank Stella retrospective opening at MoMA. By then he had left the Times to edit The New Criterion, a magazine of cultural criticism for which I wound up writing. It eventually turned into a brick-hard instrument of neoconservative doctrine, but in the eighties, it was still unpredictable, or at least predictably irreverent in the way of little magazines. In person, Hilton had none of the inquisitional, high-dudgeony crust that defined his his critical personality. He was gentle, self-effacing, charming, and avuncular. He came to my wedding. He sent flowers to the hospital when my first child was born. The vase was adorned with a light-blue plastic sign that read ITÔÇÖS A BOY! Of course I kept it, put it in a special drawer, a reminder that sometimes a piece of plastic junk can be the best expression of a complicated emotion.┬á

A few months later, when Hilton was hosting one of regular writersÔÇÖ lunches at The New Criterion, he asked about my infant son. He and his wife, Esta, whom he adored, didnÔÇÖt have children and he confessed that he had no wish for a baby. ÔÇ£I imagine caring for a baby would be like having a drunken house guest,ÔÇØ he said.┬á

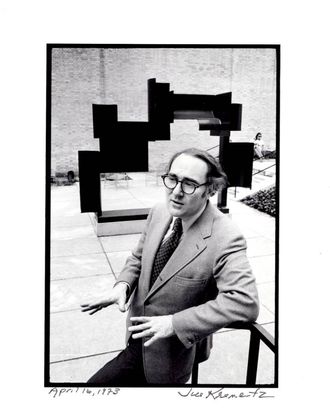

When I think of Hilton, I will probably always think of him at a museum press preview, in his glasses and tweedy jacket and a bow tie, patiently making his way through a show at MoMA or the Goog or the the National Gallery down in Washington. His default expression was one of amusement and, if you said hello to him, he was likely to regale you with a hilarious story about the latest blunder of taste committed by some art-world biggie. It never occurred to him to pull rank and see an exhibition before the other critics did, by himself, probably because the strange truth was that he liked the company of liberals and children and even bad art more than he ever let on.