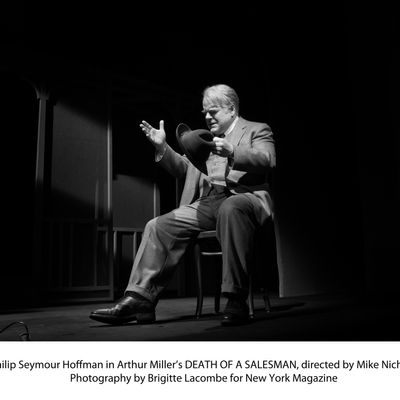

Of all Willy Loman’s famous heartbreaker lines in Death of a Salesman (“Isn’t that remarkable?” “He’s liked, but he’s not well-liked”), it’s a less-heralded snatch of dialogue that Philip Seymour Hoffman chooses to colonize with his signature Hoffmanness: “I’m fat,” Willy says, sighing like a flat tire, producing some of the most uncomfortable laughs I’ve ever heard. Hoffman seems, almost in response, to seethe and deflate all at once: Hostility and self-loathing blend perfectly. “I’m very — foolish to look at, Linda,” he confides to his long-suffering wife (Linda Emond). “I’m not dressing to advantage, maybe.” Upstairs, Biff (Andrew Garfield) — his son, his sinewy inverse — paces his childhood bedroom. Thirty-four, beautiful, and shattered, he’s a living rebuke to Willy’s polestar mythology of “personal attractiveness” and likability as all-purpose existential insurance policy. Biff’s working his way up to the play’s epiphany, the flinging-away of Willy’s dreams, and Garfield concentrates his power in his rangy, dangerous limbs, which operate as perfect extensions of his rangy, dangerous voice. Meanwhile, Hoffman, as Willy, grows more gaseous, more entropic, more psychologically atomized.

In Mike Nichols’s thunderous new production of Arthur Miller’s Salesman (really a meticulous reproduction of the 1949 original) — a suite of perfectly staged funeral games, down to the smallest role — the main attraction is this titanic grapple between American gods, embodied by two actors who know a parable when they see one and know how big a performance it calls for (i.e., oversize). Salesman is now in its early sixties, about as old as Willy himself, and attention has never ceased being paid, in classrooms and community theaters even more than on Broadway. And why not? Our economy remains dream-based, delusion still flickers in every striver’s eye, and past and present continue to smear together in a shimmery haze of nostalgia. Leave it to Nichols, our greatest living anti-stylist — nobody avoids the briar patch of “concept” like him — to point this up by resurrecting Elia Kazan’s original mounting, down to Alex North’s wind-through-the-crabgrass leitmotif and Jo Mielziner’s skeletal scenic design. Many directors approach canonical work by studiously avoiding the iconic, shaking the old shale to release untapped energies within. Nichols does the opposite. He treats the script like the scripture it is, entrusting those mile-high-written-in-flame words to actors of size and skill and voice.

Cripes, what a cast. Emond gives a disciplined, deceptively conventional performance that builds to a startling climax. The Broadway newcomer Finn Wittrock, as Biff’s neglected younger brother, Happy, infuses a character often played as a boorish dullard with a subversive sexual ambiguity — never enough to be distracting or cartoonishly revisionist, but enough to fix our attention (and ensure his invisibility to his father). Fran Kranz makes a lasting impression as the Loman boys’ nerdy foil, Bernard, and Bill Camp, as Bernard’s father, Charley, radiates disgust and empathy in perfect balance. The card-game scene, where Willy splits his attention between compulsively insulting Charley and conversing with the mental apparition of his late adventurer brother Ben (John Glover, spectral and diabolical), is a perfectly conducted trio: a dead dream, a defiant dreamer, a rejected reality. And Molly Price, with little more than a shrill giggle and a poignantly hapless shimmy, makes The Woman more than just a woman.

But the play belongs to Garfield and Hoffman, as it must. Both know how to weaponize language. (Garfield, especially, has used his Brit’s ear for High Brooklynese to great declamatory advantage: He treats Miller like Shakespeare, finding the rhythms, then secreting them inside a natural reading.) And both are performers of demon strength who are always on the razor’s edge of succumbing to their own “technique,” but, miraculously, don’t. Hoffman’s habits as an actor are, of course, better known, and may register occasionally as habits; sometimes too good a fit can be as distracting as a bad one. This is, of course, the great challenge of Willy: to play a small man larger than life. Hoffman meets that challenge fiercely, dressed to perfect disadvantage. Isn’t that remarkable?

Death of a Salesman is at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre through June 2.