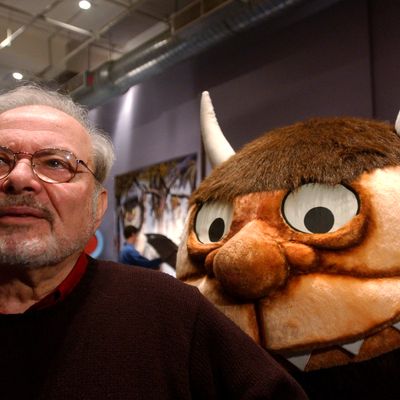

Here we are, eight days into May, and already the score is two-zero in favor of Death — which is more or less always the score, give or take several orders of magnitude. Four days ago, we lost Adam Yauch, one of the men behind the Beastie Boys. Today, we lost Maurice Sendak, who was, in his own way, also a man behind a lot of beastie boys. Max, Martin, Mickey, Pierre, and countless more, all of them running around in their naked, scowling, raging, rampaging, gleeful, gloating, havoc-wreaking (and, eventually, home-seeking) glory. Now they have become what, at least in the books, they always were: fatherless.

Sendak, who died this morning in Connecticut at the age of 83, left behind some twenty books of his own, scores more that he illustrated, various film and TV productions, a children’s opera co-created with Tony Kushner, and the darkest, most interesting, most ragged-edged hole in the history of children’s literature. Born in 1928 on a dining-room table in Brooklyn to Polish Jewish immigrants, his childhood was shaped by the Depression, his adolescence by the Holocaust. Poor, Polish, Jewish, gay: From his earliest days, Sendak understood fear, marginalization, and peril. As an adult, he extended the terrifying courtesy of that understanding to children everywhere.

History — in the form of the Caldecott Medal, umpteen other literary prizes, 17 million circulating copies of Where the Wild Things Are, and probably about that many Max costumes sold or made every Halloween — has proved Sendak right. You can grow up as coddled and suburban as you please, and still the dark will come for you: once a day, in fact, and specifically at night, the hour of bedtime and fear and (not unrelated) the time we are read to. “Whatever became of the moment when one first knew about death?” Rosencrantz wonders in Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. “There must have been one. A moment. In childhood. When it first occurred to you that you don’t go on forever. Must have been shattering. Stamped into one’s memory. And yet, I can’t remember it.” Me either. But I know the fear it brought came back to me every evening, in that dreadful, symbolic moment when my parents turned off the light and shut the door.

That’s what Sendak understood about me, and about kids in general: that, when it comes to the dark stuff, we already knew. It is also how I feel about Sendak. How could something so dark and scary and tremendous have come into my life without leaving an entry wound? Yet I can’t remember a time before I could recognize his work. Nor can American literature. Look at pre- and post-Sendak kids’ books, and you’ll see what I mean: He has burned his way into and through us all.

By chronology, geography, and background, Sendak is a contemporary of Philip Roth and Woody Allen, and it shows. Like them, he was dark, death-obsessed, and savagely, neurotically funny. His characters look like immigrants; in vain will you search for a blond, blue-eyed child in his books. (The exception is the stolen baby in Outside Over There, whom Sendak modeled on the kidnapped Lindbergh child — proof positive, in Sendak’s own youth, that not even WASPiness could ward off death.) Roth once wrote that “Jews are to history what Eskimos are to snow.” That sentence is a perfect example of brilliant Rothian nonsense: very Jewish, very funny, very ridiculous (what, being chosen by God wasn’t enough?), weirdly true-ish feeling, less convincing the longer you look at it. And yet it suggests a useful corollary. For Sendak, kids were to families what Jews were to history: marginal, misunderstood, less powerful than those around them, psychologically and morally required to rebel.

This is why, without exception, the kids in Sendak’s books are in trouble, in danger, or both. In Where the Wild Things Are, Max throws a temper-tantrum, gets a time out, and literalizes it: He steps out of time and travels alone, for days, months, years, to a land of dangerous creatures. (That temporal stretching is characteristic of Sendak’s work; time and scale, like everything else, is seen from kids’ vastly more plastic perspective.) In Bumble-Ardy, we are confronted on the first page with a pig whose family frowns on fun, refuses to celebrate his birthday, and then, injury to insult, gets eaten. In Outside Over There, a child lapses in her babysitting duties for a moment, leaving her little sister to be stolen away by goblins, who look like pint-size grim reapers (or, more disturbingly, like child refugees, albeit apparently from Hades). In Pierre, the eponymous protagonist is eaten by lions.

I love those lions — all the recurring lions, and there are many — as much or more than anything else in Sendak’s work. They are Patience and Fortitude with impatience and attitude, grinning and grrrrrrring their way across his pages. That a child both must and can hold his own against such creatures says a lot about the Sendak ethos. Kids, to him, are witnesses to, but not mere passive victims of, life’s terrors. Indeed, sometimes (and this is the only respect in which his books take the adult’s perspective), the kids are the terrors. Nearly every Sendak story is a kind of picaresque novel for the under-12 set, a tale in which a roguish protagonist roams the world before returning home wiser — or at any rate, calmer, hungrier, and sleepier. In Sendak’s world, the monsters are half-children, and the children are half-monsters. (Picture Max in his wolf costume, tail trailing behind like a vestige of an animal not yet fully evolved.) The children are also half-Hobbesian — nasty, brutal, and short — and half-Lockean, naked and innocent as … well, as a naked innocent baby, going for a midnight dip in a bowl of milk.

This mixedness is everything; it is why Sendak is so great. His kids perform sublime self-confidence but are intermittently, secretly terrified. They pretend not to care, like Pierre, but secretly they care desperately. They are tiny masters of petulance and rage, gloating, grinning, drawn to violence (all those great homemade swords!), desperately needing love: in short, human.

What is unique about Sendak stories, though, isn’t that kids are both difficult and charming. You can get that from Amelia Bedelia or Beatrix Potter or Madeline. It is that they invent and then survive their own horror stories. In Where the Wild Things Are, the misbehaving Max is sent to his room — which, however much it might seem like punishment, is also the predecessor to a great adventure. The implicit moral, and certainly the fact of the matter, is that our rooms are where we all must go, alone, to nurture a sense of imagination and identity and courage. Sure, Sendak’s kids are sometimes slighted or ignored by parents, but the most terrifying situations they survive are the ones they create for themselves. Well, welcome to life.

And farewell to it, Mr. Sendak. The king of all the wild things is gone now. And let’s not kid ourselves, there is no happily ever after in a Sendak story. In Very Far Away, the cat, the sparrow, and Martin “lived together very happily” — “for an hour and a half.” Sendak achieved his happiness in the here and now, not the hereafter, and he achieved it not pure but mixed — delight shot through with darkness, like the sheen of a rainbow on a slick of oil: upsetting to parents, mesmerizing to kids. He is gone, and unlike the boomerang characters in his books (his one concession to childhood innocence), he will not return. One wants to send him off like a foreign king, in a boat on the water, fires blazing from floating lanterns all around, on a day when New York, seen squinting through the rain, could almost be made of bottles and kitchen mixers, with monsters and kids and former kids now mostly grown-up streaming along in a strange, joyful, mournful, noisy parade behind him: all of us together, helping to send Maurice Sendak, so to speak, to his room.