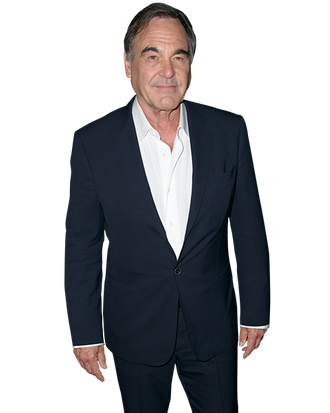

Oliver Stone’s new movie Savages — about a trio of California pot growers and the Mexican cartel trying to take over their business — is but one of the filmmaker’s many stories about how drugs affect society, history, and the individual. Stone, now 65, won his first Oscar for writing Alan Parker’s 1978 potboiler Midnight Express, about an American imprisoned for trying to smuggle hashish out of Turkey, and created a comic metaphor for eighties excess in the image of Al Pacino’s title character drowning in cocaine in Brian de Palma’s Scarface remake. Legal and illegal drugs also played important roles (onscreen and off) in other Stone pictures, including Salvador, Platoon, The Doors, and Natural Born Killers. Over the years, the director has been frank about his own ingestion of various substances, the aesthetic inspiration they’ve given him, and the legal and personal trouble they’ve gotten him into. Stone talked to Vulture about the politics and business of drugs, the casting of Savages, and his approach to filmmaking.

There’s no character in Savages that represents the “straight” point-of-view on the drug war. Why?

There’s no moralizing about the war on drugs in the movie. Prohibition is not even mentioned. That’s because to me, prohibition is a joke. It doesn’t work on any level. But my own personal views on the matter are common knowledge, and they’re outside the scope of the story that we’re telling. The setting is important, but ultimately it’s context for the working out of relationships between six characters.

You’ve visited this world before. Midnight Express, Scarface, The Doors, and in their way, Salvador, Platoon, and Natural Born Killers dealt with drugs or are often about characters that use drugs or who are flat-out addicted. Where does Savages fit into this continuum?

I don’t know if that’s true, the addiction part of what you said, because the only person in Savages who expresses any form of addiction in the movie is Blake [Lively]’s character, O, who experiences withdrawal symptoms when she’s denied marijuana. But in her case, it’s less an addiction than a concentration problem.

A lot of pot and some coke does get consumed in this movie, though, and O isn’t the only character who has a problem. Benicio del Toro’s character, Lado, who plays the cartel’s enforcer, consumes a pretty hefty amount of cocaine.

He does. But while he’s sadistic, he’s not erratic, and at the end of the day, he turns out to be a businessman. He’s not insane. Everyone changes in this movie. The only one who doesn’t really fundamentally change is Taylor Kitsch’s character, Chon, who kind of returns to where he started, and that’s because he was always psychologically grounded in the reality of the war. And the drug war is a war. I always love that theme from Don Winslow’s book of bringing the Iraq war home to roost here. If you look at the statistics, the homicide rate in Ciudad Juarez was equivalent to Baghdad in 2007 or 2008.

Supposedly there were over 5,000 drug-related murders in Mexico during the last year.

Fifty thousand since 2006. Most of the victims, according to statistics, were innocents, people in the middle. Now, we don’t know exactly if some of those people might have had a cousin or something that was involved in the drug trade. That might have been true in some cases. But in any case, it’s a reality that things are quite violent down there right now, and they are violent because there’s so much money to be made. It’s bigger than tourism, bigger than oil. Drugs are a huge part of the economy of Mexico right now. Mexico would fall apart without drug money. Over time the drug money has legitimized itself, buying a lot of malls and land, not just in Mexico but in the United States as well.

How do you think the American point of view on drugs and drug prohibition has changed since the seventies?

I don’t think America has learned much from the war [on drugs]. Sixty percent of our prison population is made up of nonviolent criminals, people who are behind bars because they ran afoul of the law by way of the marijuana trade, or the hard drug trade. We have the largest per capita prison population in the world, bigger than China, bigger than Russia, and the drug war is the reason why. We can’t afford it.

And we’ve criminalized a whole class of people and created a social chasm for young people. There are ten times more blacks than whites in jail for drugs. It’s the new Jim Crow. On top of that, you’ve got all these fucking prisoners in this prison system, prisons run both publicly and privately, for profit.

And they have no vested interest in reducing the incarceration rate because it would take money out of the pockets of people who work in that industry.

That’s the bottom line. This is not a war on drugs. This is a war for money. It’s being fought in Mexico for money, and it’s being fought in the United States for money — the United States being the biggest sap of all, because we give the most. It’s an endless outflow of money and resources to Afghanistan, to Mexico, it doesn’t matter. When George Soros tried to legalize marijuana in California, his toughest opposition came from the prison guards.

The idea that this is all ultimately about commerce gets driven home in Savages in a scene where Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s character Ben goes to one of his distribution associates and tries to explain the ins and outs of the cartel trying to buy their business. He uses the metaphor of a boutique operation getting absorbed by Wal-Mart.

This is a hypothetical fiction. The kind of drug violence depicted in Savages, with people getting killed by improvised explosive devices on U.S. soil, hasn’t happened yet. That comes from Don Winslow riffing. There’s a line in the movie, “Five guys dead in the desert, that’s huge news.” Well, maybe in the United States in 2012 it’s huge news, but not in Mexico.

Winslow has written about the drug war in the U.S., Mexico, Colombia, everywhere, in the sixties, the seventies, the eighties, and he’s done a great job. This book is a whimsy. The truth is, the cartels are so big that their business is worldwide; it’s transnational. They would have very little motivation to get into a grudge match, a shooting match, in California today, legal or not. The motivation to do it might be if your cartel were getting squeezed by another cartel.

And that’s what’s happening to Salma Hayek’s character, Elena [who plays the cartel head], in the movie. She’s responding to pressure, to the perception that in business terms, she’s dead, she’s ineffective, that she can’t run the business that she inherited from her husband because she’s a woman. Her cartel is broken up. Their methamphetamine production is down. She has to take decisive action.

I want to share a quote from an article in Marie Claire titled “Mexico’s Female Drug Lords,” which seems apropos when talking about the character of Elena:

“Mexico’s increasingly ruthless drug trade is no place for a woman. The worst kind of macho, the work is gruesome: 5612 people were murdered in narco-related executions last year, many by decapitation, now a preferred technique. But in recent years, the estimated $40 billion industry has gone coed, largely because women operate more freely here—no one suspects them of such sordid business. Women now front the cafés and salons that cartels use to launder money, and ambitious gals can go even further. Two years ago, police captured Sandra ávila Beltrán, a skintight-jeans-clad stunner who lorded over the lucrative cocaine pipeline between Mexico and Colombia. Last Christmas, beauty-pageant winner Laura Zúñiga was stripped of her Queen of Hispanic America title after being busted with her beau, a suspected cartel capo, for alleged gunrunning — fresh evidence that the insatiable cartels were becoming equal opportunity employers.”

Stone: Oh, yeah. Women have always been involved in the drug trade, and there have been a few successful ones at the top. In Colombia, there was a woman named Griselda Blanco who was called “the female Scarface” who was supposedly responsible for 400 or 500 deaths … There have been some notorious female drug lords, just as there were notorious female pirates.

Salma Hayek’s character is a survivor. She’s a very conservative businesswoman, very Catholic, who inherits this business because her husband has been killed and who tries to save the remainder of her children from being killed. She hides her daughter to protect her from danger. At one point, she even says, “I am very proud that my daughter says she is ashamed of me.” She’s a very straight woman, but she’s torn, because she wants to protect her daughter, and that becomes the key to her undoing.

There’s also a sense she is not your typical movie drug lord precisely because she is a woman. Elena can be just as ruthless as a man in business dealings. But you don’t see her lounging around the pool with a bunch of hunky young guys, or in any other situation that would seem like the movie was just taking all the usual clichés of the movie drug lord and flipping the genders.

It’s difficult for her because no matter how strong she is, she has to be constantly on guard, because of the culture of all these men who work for her. Their code. Their expectations.

Machismo.

That’s right. Elena’s not a drug user, either. She’s a very conservative woman. She tells O, “Your love story is all fucked up, baby.” She can’t imagine being in a sexual and romantic relationship with two men at the same time [like O is]. O’s position is that it’s fine. From her position, it works. The movie is told from O’s perspective, so the movie shares her point of view.

In typical cop movie terms, every single character in this movie could be coded as a “bad guy.” They could be a character that the DEA or cop hero is trying to bring down.

Well, Ben is a good guy. And O is a good guy. I mean, she’s a bit of a bunny, but she’s not a bad person. I mean, over the course of the movie she changes, and Ben does, too, against his will.

My point is, in movie terms, for a long time, with few exceptions, anybody involved in the drug trade has been presented as the bad guy, or in the process of becoming a bad guy, or a party to evil.

Here they’re all human. Even Lado. He’s a sadist, but he’s also businessman, so he’ll take a deal. [Imitating Benicio del Toro.] “My money, gimme my money.” He’s a fascinating character.

There’s a scuzzy little character moment between John Travolta’s DEA character and Del Toro that’s like something out of seventies drama. Lado drops in on Dennis. Dennis has just made himself a grilled cheese and tomato sandwich. Lado takes the sandwich away from Dennis, but before he eats it, he takes the tomato slices off and tosses them away.

[Laughs.] Yeah, that’s Benicio. Only Benicio could come up with a detail like that. He’s that way, very instinctive. To take the sandwich was probably enough, but Benicio pushes it further and makes it funny.

What did you know about Blake Lively, Taylor Kitsch, and Aaron Taylor-Johnson before you started production?

I didn’t know any of them personally when I started. Aaron was the first to get cast, in London. I liked him in Kick-Ass. I offered him either lead male role. I’d bought the book, but the script hadn’t been written. He committed to me, and he turned down two or three big films to be in this during the six-month interim that it took to get him a script. He stayed loyal to me, and I stayed loyal to him. There were a couple of points where I was tempted to cast somebody else because some bigger bait expressed an interest, but I felt like Aaron was the right guy, so I didn’t waver.

The moment I found Taylor, he’d just come off of Friday Night Lights and Battleship. To play Chon, I needed a foil for the character of Ben, somebody who was stronger than Ben and could back him up. Aaron and Taylor are both great-looking guys. They look sexy onscreen together. Kind of a Newman-Redford, Butch and Sundance thing. Aaron as the talker, the brains of the operation, Taylor as the quiet killer.

Blake was the last one of the three main roles to get cast. She wasn’t the character in the book, or even the character in the original script. The character [as written] had more of a punk-rock, Girl With the Dragon Tattoo kind of feeling, a Gothic nihilism. For whatever reason, there was a lot of that kind of female type around in films at that moment — Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, Sucker Punch, and so forth — so I didn’t want to do that again. Then Blake walked in. She had that kind of Southern California feeling. She looked like the beach. But Blake has her own point of view. She’s a very tough young woman, very smart, street smart. She had a lot of ideas about the script. Of all the main actors, Blake, Benicio, and Salma probably gave me the most input. They wanted to change things, and in a lot of cases they did talk me around to their points of view.

Did you feel a particular affinity for Kitsch’s character Chon? I ask because you and Chon have some biographical details in common. You were a decorated Vietnam veteran, then you came home and slipped into this counterculture scene. It’s a different era, but Chon’s on that wavelength. In real life, if you saw that guy walking on the beach smoking a joint, you might not guess that he knew twenty ways to kill you.

But in Chon’s case he’s coming full-circle. He’s home from Iraq, but this is a world he’s familiar with. He’s a beach guy. He came from that area. But yeah, I did feel a connection. There’s a dichotomy there. That’s something I get into in a lot of my work. In a way, these characters, Chon and Ben, are continuing ideas from Platoon. Chon is Barnes; Ben is Elias. Barnes is force; Elias is negotiation. I like that contrast between Ben saying, “Let’s negotiate,” and Chon saying, “You don’t negotiate with savages.”

I bring this up because the tone of Savages is pretty striking considering how long you’ve been doing this. You’re 65 now. The characters are in their twenties. But this movie doesn’t have the kind of rueful, melancholy, “If I knew then what I know now … ” kind of feeling. It’s not what I call an “Old Man Movie.” You’re not looking back at a youthful past. It feels like the storyteller is in the house with these three young people, like Oliver Stone is the invisible fourth roommate.

The three actors did that to me, just by being so damned attractive. I like to photograph good-looking people. I always did. But Aaron and Blake and Taylor also kept me young just by being themselves, by bringing their own points of view. There were a lot of points where they’d want to change dialogue because they didn’t like a particular word or didn’t think it would sound like what a person in their twenties right now would say.

In terms of the whole movie, people ask me, “Why was it shot this way?” and I answer, “Because I think of myself as an actor-director.” You know the kind of actor I mean? One who, every time he does a movie, he becomes that character. He takes on that role, but then you see him later in real life and he doesn’t resemble that role. I think that goes on with me, too. Every time I do a movie, I try to become that movie. I immerse myself in research, so much that it soaks through me. The styles of the movies reflect that. I don’t think you could call me a stylist who repeats the same thing over and over — at least not in the same way that, say, Hitchcock had a definite style, and that Kubrick did.

Oh, you have a style. You might not be aware of it, because it’s you behind the camera. But your films have a particular energy, a particular vocabulary, that’s very recognizable.

[Laughs.] A political vocabulary!

Sure. But also visually. Technically. No, it’s not exactly the same every single time you make a film. But there are periods where you’re working in a certain mode. Then, over time, it evolves into something else, without losing that Oliver Stone–ness, however the viewer might choose to define that made-up word.

Well, yeah. It changes from movie to movie. This year, I’m into this particular story, Southern California meets Mexico noir, or whatever you want to call it. Last time I was into a Wall Street style in Wall Street 2, a bit more classical, maybe, but looking for ways to visually communicate the phenomenon of what happened to the U.S. when the financial system collapsed. A year or two before that, I was immersed in the world of President George W. Bush with W. — a world unto itself, within America. And so that film reflected the kind of flattened worldview of that president. You saw Alexander — all my travails with Alexander! — and there’s an Alexander style, too. There’s something that seeps into my mind-set each time and transforms what ends up onscreen.

Can you describe what it feels like to go through that process?

It’s very intense, and ultimately very painful. I’ve actually done some acting, but I’m not talking about that. I’m using acting as a metaphor. For me, filmmaking is like acting, in the way that it takes over you. It becomes part of you. The role, the lines, the personality of the character — it’s all in you. It’s in your dreams. You think about the character without meaning to, in your sleep. I compare the process to acting because of that quality of immersion, that attempt to internalize the material and become the story. If the attempt is successful, the result is a good or at least an interesting film. But once it’s done, it’s over, and the actor goes back to being himself.

When you interviewed me a couple of years ago, you may not have known it, or had any way of knowing it, but you were not just interviewing me. You were interviewing the residue of the last movie that had consumed me. The person you’re interviewing today has gone through the same process, but with different material, and ended up in a different place. I have to detach. I have to move on. I have to keep looking ahead to the next thing. If you see me again next year, I won’t be the same person. The actor in me will have forgotten the last role, the lines. If I ever get to do another feature film, God willing, or God forbid, it’ll be the same process.