Saltz: The MetÔÇÖs ÔÇÿRegarding WarholÔÇÖ Has Nothing to Say

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is unsurpassed at presenting more than 50 centuries of work. I go there constantly, seeing things over and over, better than IÔÇÖve ever seen them before. Yet even we who love the Met know that with notable exceptions it has pooh-poohed, misconstrued, or messed up the art of the second half of the twentieth century pretty much since it was made. Now itÔÇÖs doing it again ÔÇö but worse.

ThereÔÇÖs a shallow, pandering fecklessness to the pseudo-extravaganza ÔÇ£Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years.ÔÇØ Its underlying idea is so shopworn and flighty it can come as a surprise only to the Met: Andy WarholÔÇÖs art and what curators Marla Prather and Mark Rosenthal deem ÔÇ£the Warhol phenomenonÔÇØ are really, really influential. Prather wonders, ÔÇ£Is there anyone whoÔÇÖs had a bigger influence?ÔÇØ Rosenthal offers, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm starting to think of WarholÔÇÖs impact like a meteor striking the Earth.ÔÇØ To prove what anyone whoÔÇÖs looked at art in the past 40 years already knows, they brought together about 50 artworks by Warhol, then installed them with approximately 100 works by other artists. Nearly all the other artists are usual suspects from the ┬¡aesthetic-economic auction complex, blue-chippers like Damien Hirst, Takashi Murakami, Jeff Koons, Richard Prince, John Currin, Douglas Gordon, Anselm Kiefer, and Francesco Vezzoli. (All of whom just happen to show with Gagosian Gallery. Why not subtitle the show ÔÇ£LarryÔÇÖs Got TalentÔÇØ? Or ÔÇ£Comfortably Numb.ÔÇØ)

ÔÇ£Regarding WarholÔÇØ has the unusual distinction of being a very bad show with very good work. The exhibition takes fantastic advantage of the MetÔÇÖs space and reach. Almost every Warhol is first-rate and in excellent condition. Yet you wish instead of sections about celebrity and appropriation, the show had taken on more abstract but far deeper Warholian content like hoarding, neediness, and disembodiment. After all, this is the artist who said, ÔÇ£Sex is so abstract.ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs barely anything here about some of his favorite tools, like the tape recorder and the Polaroid instant camera. Why not have the courage of your own convictions and include Martha Stewart, who utterly followed AndyÔÇÖs footsteps around the businesses of d├®cor, branding, and endorsement? The show avoids great but problematic work like WarholÔÇÖs ÔÇ£cock drawingsÔÇØ (or the Brigid Polk print of Jasper JohnsÔÇÖs penis owned by Warhol). Nor does it focus more on the 50 to 100 portrait commissions he did annually for around $50,000 apiece. Instead, everything looks crisp, way too crowded, and predictable: This is more like an auction sales room or a high rollerÔÇÖs private museum than an exhibition.

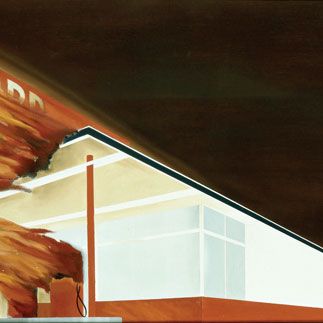

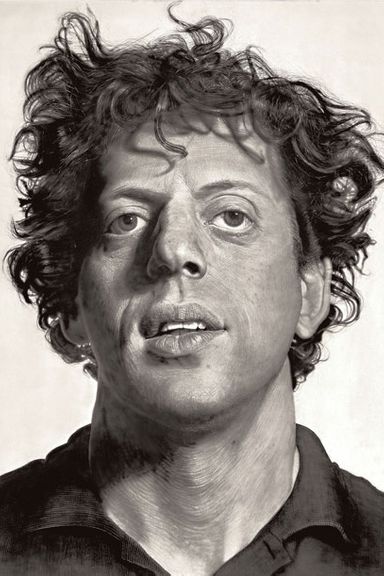

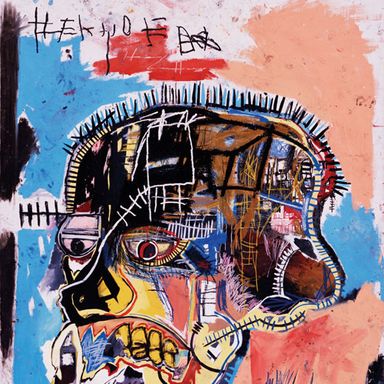

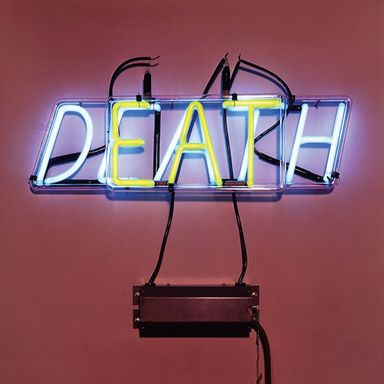

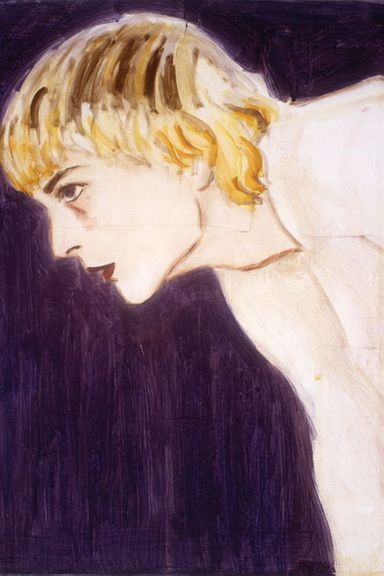

The show defangs everything. A Bruce Nauman neon work flashing the word DEATH, included because Andy also dealt with death, comes off as a bauble. A Basquiat skull-head is on hand, because skulls equal death, too. A Matthew Barney setup photo of someone with a gun? Yup, death again. So it goes, for ten long galleries. In the section grouped by celebrity, or maybe celebrity lips, near WarholÔÇÖs portraits of Elvis, Marilyn, and Brando, we see sexy lips in portraits by Chuck Close, Elizabeth Peyton, and Karen Kilimnik. Cindy Sherman is great, but the only reason sheÔÇÖs here (other than the fact that dull curators canÔÇÖt do a show without her) is that sheÔÇÖs made a few pictures where she looks like a movie star, and Andy liked those sorts of people too. One gallery shows art of cars and gas stations. Ed RuschaÔÇÖs burning Standard station is near John BaldessariÔÇÖs painting of a car and a Barney picture of five cars. By the last galleries I was so dispirited IÔÇÖd look at the first work IÔÇÖd see and predict what would come next. Cory ArcangelÔÇÖs floating-clouds video? WarholÔÇÖs floating silver clouds. MurakamiÔÇÖs flower paintings? Flowers. (HowÔÇÖd ya know?) I donÔÇÖt think I stumbled on a single surprising juxtaposition or one that deepened meaning.

By reducing everything this way, ÔÇ£Regarding WarholÔÇØ completely negates ┬¡AndyÔÇÖs radical way of making art, his astonishing ideas about color and skidding images, how he made art seem easy and being gay great, the ways he transformed commercial art into high art and high art into mass entertainment, how he turned himself into an icon, an anti-hero, and an ambience. The rest of the artists fare no better.

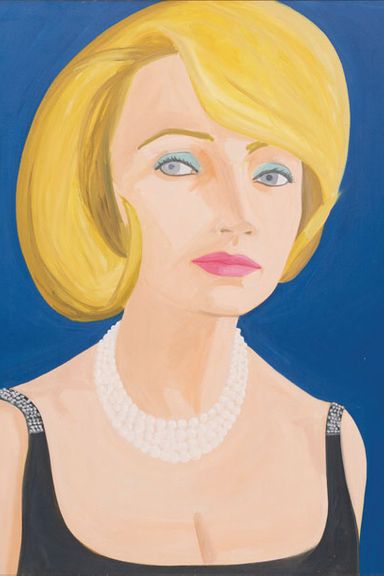

Everyone agrees that Andy is in the air we breathe. Yet artists whose work seems to resemble his also breathed other air. A number of the artists here defy the showÔÇÖs conceit and insist that they werenÔÇÖt influenced by Andy. Alex KatzÔÇÖs early ideas about color and figures on flat grounds precede WarholÔÇÖs. In the catalogue, Katz jokes, ÔÇ£Good artists steal, and [Warhol is] a good artist.ÔÇØ Vija Celmins says she was ÔÇ£not interestedÔÇØ in what Warhol was up to back when she was making her own early black-and-white images of subjects like race riots from magazine covers. Though Chuck Close says Andy ÔÇ£was a great painter,ÔÇØ Katz says he was ÔÇ£a terrific graphic artistÔÇØ but ÔÇ£he couldnÔÇÖt paint.ÔÇØ

Last week, the Andy Warhol Foundation announced that itÔÇÖs selling off its huge holdings of AndyÔÇÖs work, converting itself from an estate into a cash fund that will give artistsÔÇÖ grants. ItÔÇÖll effectively be doing what the Metropolitan purports to be trying here: making real, meaningful connections between WarholÔÇÖs legacy and new, vital work. Meanwhile, up at the Met, what weÔÇÖre left with is a cynical gimmick to bring in the crowds and spruce up the museumÔÇÖs image. Warhol, who loved commerce, will give it all away, whereas the Met, which is supposed to be above it all, will be raking it in. In the future, every museum will do fifteen Warhol shows.┬á

Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Through December 31.

*This article originally appeared in the September 24, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.

Ai Weiwei (2010)

Jeff Koons (1988)

Ed Ruscha (1966)

Alex Katz (1964)

Photo: Digital Image ? The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY / ? Artres

Chuck Close (1969)

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1981)

Bruce Nauman (1972)

Elizabeth Peyton (1995)