On a rainy early-spring evening, a parade of Barbie dreamgirls and gays make their way to see Nicki Minaj, the sound of high heels crunching on the pavement. It’s the first night of her run of Northeast shows on the Pink Friday 2 World Tour at the Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey. While walking toward the venue, a woman in a layered pink miniskirt, a bikini top, and Lucite coral kitten heels bumps into someone who is demonstrably not a Minaj fan: gray hoodie, jeans, a distinct lack of Big Cunt Energy. The other person doesn’t even notice, but this woman clocks the disrespect. “You ain’t a Barb,” she says mostly to herself as she hobbles along the pavement. “You an ugly bitch.”

Taylor Swift has her Swifties, Beyoncé has her Beyhive, and Nicki Minaj has her Barbz, a notoriously brutal fan base whose members will do anything for their icon. Barbz have publicized the numbers and addresses of Minaj’s critics in the media, have harassed the woman who accused Minaj’s husband of sexual assault, and have sent graphic messages to a former Barb who left the standom for disagreeing with Minaj.

In January, Megan Thee Stallion released “Hiss,” which featured a hotly contested line — “These hoes don’t be mad at Megan / These hoes mad at Megan’s Law” — that was perceived as a jab at Minaj’s husband, Kenneth Petty, a registered sex offender who was convicted of sexually assaulting a 16-year-old girl at knifepoint in 1994 when he was 16. Minaj went live on Instagram insulting Megan and making wisecracks about her late mother. The Barbz took it a step further, threatening to deface and vandalize Megan’s mother’s grave. It got so bad that the cemetery reportedly had to beef up security after Barbz leaked the location of her burial site online.

So suffice to say it isn’t the best time to be a Barb. And there is perhaps no star who interacts directly with their fans as much as Minaj. That creates its own type of parasocial relationship, beyond simply loving a musician and feeling close to them through their lyrics: If you speak even slightly ill of Minaj on TikTok, she will find it, and she will comment, even if you preface your critique with your Barbdom.

Lately, attention around standom in general has reached a new fever pitch. Donald Glover made a whole Amazon show about it, Swarm, while some artists are trying to relitigate their relationships with their stans — Britney Spears has had to tell her Instagram followers to relax and let her live, and Doja Cat has been hostile to the concept of an organized fan base. But Minaj leans in and treats the internet like a normal person who doesn’t enjoy being insulted online, as if she didn’t have 229 million Instagram followers who would join her in the response.

Is all this energy worth it? Could a Nicki Minaj show be so spectacular that it inspires this level of ugly, terrifying fealty?

Before the concert even starts, paramedics wheel away a young woman in a mysteriously wet minidress as she vomits into a paper cup. Her sister is crying — they’re going to miss the show. The crowd varies dramatically throughout the sold-out arena: plenty of Gen-Z kids too young to buy beer, elder millennials who grew up with Minaj, some Gen-X-ers who admire Minaj’s do-whatever-you-want attitude.

Joseph “Jojo” DiMaria, 16, came to the tour decked out in a floor-length off-shoulder pink gown and knee-high matching pink gladiator heels with fluffy bows and dangling heart-shaped rhinestones. He’s here with his friend and former babysitter Teresa Brennan, 24. She snaps at him to cut it out when he gawks too long at a man walking by. “You’re not old enough,” Brennan says. DiMaria bats his long eyelashes.

DiMaria identifies as a Barb and nothing less. “A fucking Barb is the one that defends Nicki Minaj no matter what. A Barb is there 24/7 for the queen.” He delivers these words like a pledge of allegiance. “I hang my Barb flags on my camp bunk at my autistic summer camp.”

Brennan nods. “Every year, since he was, like, 13.”

The Barbz live in Gag City, an inside joke between Minaj and her fans, which started in the lead-up to her fifth album, December’s Pink Friday 2, mostly in response to frenetic and inconsistent information about the album’s release date and the tour. Fans shared AI-generated art of a futuristic all-pink world, waiting for Minaj to “gag” them with the record. I ask Barbz what Gag City is. Answers vary from “I have no idea” to

“a beautiful city with abortion and gay rights” to “Gag City is everything, baby!”

According to them, Gag City is under attack — by nebulously defined “haters,” by Cardi or Megan fans, by a music industry that wants to deny Minaj the success she deserves. (Why no Grammys? Some Barbz consider this nothing short of a conspiracy against the queen.) But the reality is that while plenty of Minaj songs are blockbuster singles (her and Ice Spice’s “Barbie World” closed last summer’s Barbie), and while her albums are largely commercially successful (Pink Friday 2 debuted at No. 1), her online rants and complicated personal life appear to have irreversibly impacted how she’s perceived. Barbz see Minaj as sweet, sensitive, and generous — they cite unspecific examples of her supposedly paying for Barbz college tuitions on X — but beyond her own stans, she’s more frequently viewed as cruel, virulent, and unhinged.

Whatever Gag City is, getting there is expensive. Ajadi John, 19, and TJ Harris, 20, both flew to Newark for the show — Harris from Virginia and John from the Virgin Islands. Those flights and tickets and new outfits aren’t cheap: The concert experience is costing John around $3,000. “It sounds crazy,” he concedes. (Harris didn’t even realize his friend had spent so much; he gapes at him when he shares the grand total.)

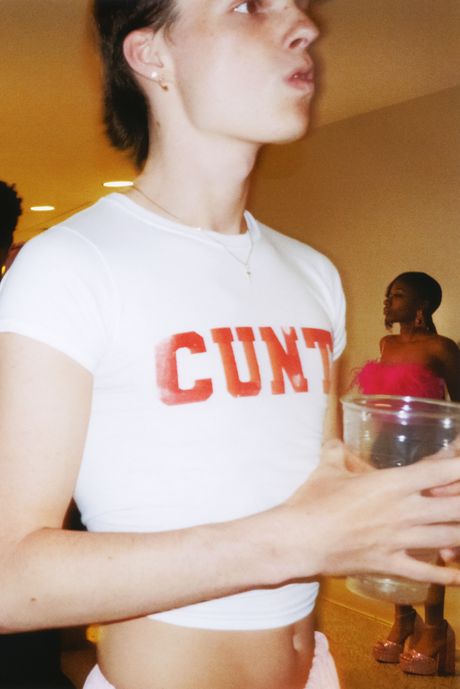

The two are among the more muted Barbz here, even though they’re dressed for peak Barbdom, Harris in clear pink sunglasses with silver stars, John in a bright-pink Kirby letterman jacket and white Louis Vuitton sneakers. Most of the crowd got the same memo about the dress code — high-femme Barbie queer Harajuku futuristic Madonna-and-whore pink girlie cunt fantasy. This show isn’t just a chance to see Minaj perform. It’s a chance to be seen by other Barbz, to show off your dedication based on presentation, to prove your allegiance by dropping a few hundred at the steadily emptying merch table. At one point, DiMaria bolts away from me and Brennan and after a group of 20-somethings rapping “Roman’s Revenge” in order to join in. Everyone should know how well he knows these words.

Mary Tapican, 23, a Starbucks supervisor, and her boyfriend, Dante Saunches, 24, flew in from Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, for the show. Tapican is a fiercely devoted Barb and an immigrant from the Philippines — Minaj was the first female rapper she ever heard. A breakup when she was 13 coincided with 2014’s The Pinkprint. “That Pinkprint era just spoke so many words to me: I don’t need you to love myself,” she says. This isn’t just Tapican’s first Minaj concert; it’s her first live show ever.

Saunches is doing what a lot of men here are doing — playing Ken to all these Barbies. He likes Minaj’s music, though he wouldn’t categorize himself as a Barb, despite the matching black-and-pink motorsport-inspired outfit he’s wearing with his girlfriend. The Nicki fervor, he says, is far louder in person than he understood from afar. “People are actually ride or die,” he says. “It doesn’t matter where she goes or what she does; she’ll always be the sunlight in the darkness for everybody here.”

Tapican is one of very few Barbz here willing to admit to fighting online in defense of Minaj. Her latest spat was in the YouTube comments of one of Cardi B’s music videos. “Someone was like, ‘Oh, she wrote this.’ But I was just like, ‘Did she, though?’ ” she says. (Cardi is often accused of using ghostwriters for her lyrics.) For Tapican, showing up to see Minaj live is one way to support her fave; going at it with Cardi fans is another. “Of course, I’ll pick Nicki’s side, but it has to have some kind of truth to it,” she says.

Online, Barbz will often eat their own if it means defending Minaj, but at this concert, there’s a little room to be critical. “She’s always late,” says John, the Virgin Islands teen, talking about Minaj like she’s his annoying friend who’s always pulling up to brunch when the bill comes. “I spent $3k! You can’t be coming out late and stuff. As soon as it hit eight, you gotta be there!” (Minaj wouldn’t hit the stage until around 10 p.m.) Most of the Barbz I spoke to said that they’re not a big fan of Minaj’s husband but add that it’s not their place to judge. “I don’t know the whole story,” says William Marcjanik, a fan from Bergen County wearing an “I am Kenough” pullover. “No one knows the guy. They’re all gonna be like, ‘Sex offender? Write him off.’ Maybe he’s actually a great guy but he fucked up 20 years ago.” DiMaria doesn’t want to talk about Petty, but Brennan does. “He’s not great,” she says, wincing. DiMaria takes a few steps back from me and my recorder. “You gotta take that out,” he says. “Nicki sees this interview, she’s not going to be hugging me.” He warns me, with a wink, against writing a negative review of the show or of the Barbz, pressing a pink-gloved hand on his chest in terror. “They’ll find your family. They did it before. They’ll do it again.”

A lot of these Barbz are still listening to Cardi and Meg — just quietly. Several of them said their greatest wish is for a drama-free era: If only the girls could just get along, record a super-hit, and let us all live in peace. When Barbz do, in brief moments, criticize Minaj, they do it while looking around nervously at other fans in the venue. What if someone hears them? What does a citizen’s arrest look like in Gag City?

The Barbz here seem to agree, though, that there’s almost nothing Minaj could do to put them off. The only two good reasons to stop being a Barb? Homophobia or murder. “She would never,” Brennan says to DiMaria, who nods deeply. Marcjanik says “not even cannibalism” would stop him from being a Minaj fan. “She’d have to kill her baby,” Debie Silpa, 54, told me. “If she cuss someone out, I don’t care. They probably deserve it.” Silpa respects Minaj’s strength, her boss attitude, and the fact — and Barbz do treat this as undeniable fact — that Minaj writes her own raps. “I think she’s very gentle inside. She just has a strong personality like us,” Silpa says, motioning to her and her very tall friend, head-to-toe in pink and rhinestones and lashes. “We don’t put up with no shit either.”

When Minaj finally takes the stage several hours late, she receives applause so thunderous it feels like the arena might rip clean in half. Rumors of Minaj’s poor live performance have been grossly exaggerated. She raps almost every word, rarely using a backing track. (Her guest, Fivio Foreign, did his entire minutes-long performance with one.) Her performance is crisp and boisterous and funny and sexy. She pulls people out of the crowd and asks them to sing, snatching the microphone away in mock disgust when they’re not operatic enough. She hurls T-shirts into the crowd with a velocity that you might reserve for a snowball fight. (“Sorry,” she says absently when she hits someone in the face.) The crowd loves being shit on by their queen. She doesn’t really do choreography, and the stage production is limited compared to, say, the Renaissance World Tour, but she doesn’t need to do too much; Minaj is ruling a kingdom for two hours every night of this tour.

As she raps “they need rappers like me / so they can get on their fucking keyboards / and make me the bad guy,” from “Chun-Li,” the crowd screams it back at her. “Thank you, from the bottom of my heart, for never leaving me,” she tells them.