Theatergoers get their choice of tainted hellscapes this week, one from the canonical past, one from the contaminated near-future. First up, Manhattan Theatre Club and trusty retainer Doug Hughes bring us the durable Ibsen fist-shaker An Enemy of the People, in an earthy new adaptation by British phenom Rebecca Lenkiewicz. (Little known on this side of the Atlantic, Lenkiewicz became — in 2008 — the first living female playwright to debut an original at the Royal National Theater’s Olivier Stage.) Ibsen famously stated he wasn’t sure if Enemy, with its impassioned speeches, self-mythologizing Über-hero, and huge tonal swoops, was comedy or drama.

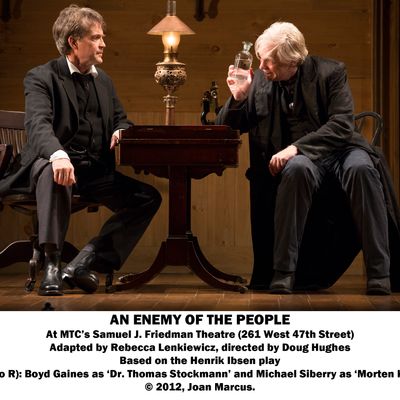

Hughes doesn’t seem sure either, so he’s covered his bases. The result is a stilted collision of interpretations — the well-made play knocked together with a few planks of crooked ironic timber — that reflects but doesn’t really react to the lack of critical consensus on Ibsen’s great polemic. Is Doctor Stockmann (Boyd Gaines), dramatic literature’s original whistleblower, a great man, a great fool, or a slightly monstrous, Nietzschean hybrid of the two — a forerunner of Solness and Borkman? Don’t worry, there won’t be a quiz: It’s impossible to get a grip on the big ideas in Hughes’s brisk, dutiful, ephemeral production, which exists mostly to showcase a just-this-side-of-hambone performance from the always-arresting Gaines.

Enemy, a social-realist barnburner in its day, was out of fashion by the fifties, when it was famously (and rather chest-thumpingly) reclaimed by Arthur Miller. Since then, several others (including Richard Nelson and Christopher Hampton) have grappled with Stockmann, a middle-aged crusader for science and reason who naïvely believes he’ll be universally exalted for cramming an inconvenient truth down the throat of his one-industry town. When he discovers that the waters of the new local health spa are rife with bacteria from a nearby tannery, Stockmann believes he’ll be lauded for preventing an epidemic: Visions of parades and parties dance in his head. Instead, he ends up ostracized, as the entrenched interests — personified in his saturnine brother, the mayor (Richard Thomas) — take him apart. The process shocks Stockmann, but will be familiar to anyone who’s followed the climate-change debate, the fracking flap, or any other mind-bendingly exigent modern confrontation between the health of the polity and the health of the economy. The capitalists simply refuse to concede to scientific fact; the working men are easily incensed against the henny-penny elitist know-it-all who wants to stopper job-growth and raise taxes; and the press is reliably craven and opportunistic. “The most dangerous public enemy is the majority!” concludes the apoplectic Dr. Stockmann. “Who forms the majority? The wise or the foolish? You have to concede that idiots outnumber geniuses. Are you telling me the average man should rule over the great?”

Now we’re getting somewhere: It’s Idiocracy, 1882! From Schopenhauer to De Tocqueville to Ibsen to Mike Judge, the fear of lumpen little-men with lumpen little-minds and easily marshaled armies of ignorance who mass at the drop of a hat (or a web-video) to defend the indefensible has always been a wonderful source of dramatic hysteria. Stockmann’s towering master-rage at the great gaping peasantry — you don’t need a doctor, you need a veterinarian, he tells them — was precisely the aspect of the play Miller tried to downplay in his adaptation. But, as Gaines divines, it’s also Stockmann’s most interesting trait. Without it, he’s little more than a preening ingenue with a touch of ADHD. With it, he’s fully human: Stockmann, betrayed by a “solid majority” who transform into a savage mob the moment they hear news they don’t like, abandons the facts he worships just as quickly as his opponents. Threatened, he wishes nothing less than extermination on his boneheaded attackers.

Gaines, cherub-cheeked and sharp-elbowed, is having a ball. His Stockmann is a righteous child, a more charismatic Al Gore minus the late-career humility. When he finally arrives at a working theory of himself and his place in this fallen, foolish world — to be Good is to be Better, and, as a consequence, to be Alone — it’s a cosmic joke. Stockmann will fight for and against the World by himself, supreme and singular, a superman-vigilante. (Was this withering mock-heroism what gave Hughes the idea to commission a strange, synth-driven John Carpenter–meets-Vangelis score from David van Tieghem?) But Gaines really is alone up there: Stockmann’s chief antagonist is his brother the mayor, whom Thomas presents as an odd, toddling wind-up toy with a marionette’s painted smile. Thomas is showing us the strings, apparently with Hughes’s encouragement, but his scenes with Gaines feel fundamentally mismatched: Two men from two different universes, talking past each other. A lip-curling Michael Siberry, as Stockmann’s amoral father-in-law, fares better, in two delectably sour little scenes where he punctures the good doctor’s bubble of self-satisfaction. This Enemy is full of caricatures at war with other caricatures; everyone’s highly animated, but do we ever feel the fate of Toontown hangs in the balance? Not really.

Whereas visceral peril is ever-present in Adam Rapp’s Through the Yellow Hour, his latest postapocalyptic pensée. Five minutes in, the guts of a gibbering drifter (Brian Mendes) have already been sprayed across the back wall by a nervy nurse named Ellen (Hani Furstenberg), and we come to realize we’re in a New York–turned-Mogadishu, a collapsed city under constant siege from a suspiciously well-equipped radical-Islamist militia colloquially known as the Egg Heads. (They wear giant, Storm Trooper–ish helmets that are very, very funny to look at, though we’re not given full permission to guffaw.) Because a modern American city abandoned to the Taliban isn’t near catastrophe enough for Rapp, we’re also given to understand that much of the population has been decimated by biowarfare, the men have been castrated, and the women tagged like livestock by some Orwellian authority. (The debt to Alan Bowne’s Beirut is noted.) The Egg Heads and their brutal Sharia hijinks, it’s whispered, are just a front for something even darker and more homegrown, an eugenicist plot emanating from the American heartland. This being Ellen’s story, a bug’s eye view, elaboration is not required: Rapp just wants us to sense the contours of his nightmare, a pungent blend of various Gothamite paranoias. (Culture-war loathing towards the White Other, terror-war insomnia attached to the Brown Other, etc.)

It’s all not-so-vaguely ridiculous, of course. Rapp’s incontinent egregiousness, once his calling card, now amounts to self-parody. (One lengthy description of a torture scene is so detailed, so granularly grisly, so protracted, it finally slips from Euripidean horror to B-movie hilarity: Halfway through, I started hearing it recited by Samuel L. Jackson.) And his weakness for poetic pretense in the midst of urgent drama cries out for some kind of literary intervention. He asks his brave, flawlessly focused castmembers to drop trou in every show — must he also force them to say stuff like this? “During the Yellow Hour [the daily cease-fire] sometimes I go to the East River and just watch the sun coming up,” burbles Maude (Danielle Slavick), who’s just been forced to strip naked, at gunpoint, when Ellen demands to see if she’s carbuncled with plague under her Terry Gilliam apoca-wear. After a half hour of terse, hollow-point dialogue, Maude gives us this little rhapsody: “The sickly water going surprisingly silver … the rare seagull … So still in its flight it looks somehow pinned to the sky … It’s amazing to me that there are still seagulls … ”

It’s amazing to me there are still Adam Rapp plays — at least, this particular species of them, where the gothic and the adolescent seem to congeal at the bottom of the playwright’s Netflix queue — but boy, can he direct the hell out them. Rapp’s skill as a director has increased in indirect proportion to his persuasiveness as a playwright. He has a weakness for the cinematic that he’s turned into a strength, and Through the Yellow Hour carves camera-ready moments out of darkness. (He’s assisted by Andromache Chalfant’s bombed-out set — a study in depths, in every sense — and the deliciously ill-tempered, Se7en-ish lighting design of Keith Parham.) Rapp has proven a skilled visual editor of his own work; I wonder what would happen if he began that process on the page.

AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE is playing at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre through Nov. 11

THROUGH THE YELLOW HOUR is playing at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater through Oct 28