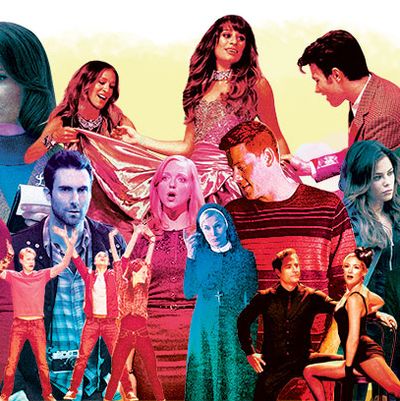

Ryan Murphy is the king of the Bad Relationship show. The affair is volatile and frustrating, and there are long stretches when you don’t get much from it and feel like a sucker for becoming involved; but then, just when you decide you can’t take it anymore, the show does something so wonderful and surprising that you fall in love again. I’ve gone through this range of reactions while watching Murphy’s nightmare soap American Horror Story, which just started its second season, and his high-school musical Glee, which is now in its fourth. I almost bailed on AHS midway through season one, when it seemed as though it was making things up as it went along, and I’ve announced publicly that I was done with Glee at least three times. Yet here I am, still watching both. Why? Because Murphy’s shows—made in collaboration with writer-producers Brad Falchuk (Glee, AHS) and Ian Brennan (Glee)—represent TV’s virtues and faults in their most heightened form. Scripted TV can be as tonally elastic as literary fiction, cinema, and pop music; it can be “realistic,” exaggerated, even figurative or fantastic, within the space of one episode. Yet few shows indulge that freedom, going anywhere their imagination takes them, and accepting the fact that the results will be hit-and-miss. The short list includes Louie, Wilfred, Portlandia, Community, and anything by Murphy, TV’s most polarizing, problematic showrunner. For all its trashiness and willy-nilliness, Murphy’s work gives me potent highs that neater, more measured shows don’t—ones that derive from his prizing exuberance over consistency, and the juxtaposition of beautiful moments with mediocrity, which makes the great bits pop like flowers in a junkyard.

Season four of Glee, which sent McKinley High School graduates Kurt (Chris Colfer) and Rachel (Lea Michele) to study musical theater in New York, is a great example. I quit watching near the end of season three following a run of episodes that were half-assed even by Glee’s standards. I came back this year after friends (enablers?) told me it had gotten good again. I could spend this whole column citing this season’s missteps; at the top of the list would be the scenes with McKinley’s new freshmen, who feel like dull replacements for the aged-out original cast, and anything with glee-club coach Will Schuester (Matthew Morrison) and his fiancée, guidance counselor Emma Pillsbury (Jayma Mays), who’s been so underused recently that I keep forgetting she’s on the show. But I’d rather praise the New York sequences, which invigorate Glee even as they beg us to believe unbelievable developments, such as tight-assed Rachel transforming into a Broadway trouper, and the greenhorn Kurt’s instantly becoming the confidant and creative sounding board of his boss, a superstar Vogue editor (guest Sarah Jessica Parker). But I’m willing to live with Glee’s irritants because, at their most raw and calculatedly naïve, the New York scenes remind me of what it was like to be on the cusp of twenty: sensitive and horny and ambitious; wanting to hold on to the person that you were, even as you strive to become the person you think you’re meant to be.

The fourth episode, “The Break Up,” was Glee at its most excessive yet assured. When it became clear that it was going to bust up not one, not two, but four couples in an episode—Kurt and Blaine (Darren Criss); Rachel and her old high-school sweetheart Finn (Cory Monteith); Will and Emma; and Brittany (Heather Morris) and Santana (Naya Rivera)—I laughed out loud at its Glee-ness. But overall this was a somber installment, with unusually stripped-down musical numbers, the best of which were set in a piano bar called Callbacks. Finn, visiting New York after an aborted stint in the Army, watched Rachel duet with her fellow student and suitor Brody (Dean Geyer) and realized he’d made a horrible mistake by going into embarrassment hibernation and not calling her for four months. Then Blaine sat at the piano and performed an on-the-edge-of-tears rendition of Katy Perry’s “Teenage Dream,” the song with which he’d serenaded Kurt two seasons earlier. Both numbers were about the pain of realizing that geography and maturity have opened an unbridgeable gulf in a relationship that once seemed perfect.

American Horror Story, which I’ve described elsewhere as Glee’s evil cousin, turns some of the alienating qualities of Murphy’s shows—short attention span; uninterest in character consistency; an eagerness to get a rise out of viewers—into strengths. Early in season one, I was put off by the show’s fast-forward pace and lack of dramatic connective tissue. Every few minutes there was a Big Moment—a rape by a black-rubber-suited ghost, a deranged monologue by Jessica Lange in Tennessee Williams freakazoid mode—and the horror classicist in me rebelled. But over time it became clear that this was the show’s aesthetic, and that, whatever issues I had with it, it was something new: all-highlights horror; a glossy, soapy, trailer-ized version of a ghost story, possibly derived from the experience of watching films in ten-minute segments on YouTube.

And in retrospect it became clear that the show was more meticulously constructed than I’d thought. For the most part, the pieces fit, the whole thing working as both black comedy–domestic satire and horror-tragedy. In the final stretch—a slide-trough to hell that showcased operatic gore worthy of Dario Argento—American Horror Story killed off every recurring character. Amazingly, that was okay, because the biggest of the show’s big surprises had to do with the format: All this time you thought you were watching an ongoing series, but you were actually watching a mini-series, one that would reboot itself with a new plot, a new location, and much of the same cast filling new roles.

We’re just three episodes into the second season of American Horror Story, which is set at a Catholic-run mental hospital and subtitled Asylum, but already it feels like an improvement on the first. The jumpy energy and jaunty perversity are still there, but the period setting (1964) gives the story more resonance, classy pop music, and a semblance of context. Just as Glee makes a point of satirizing and sentimentalizing society’s misfits and outcasts, alternately bullying and embracing them, Asylum is about the pain of not fitting in. But the stakes are greater here. The powers that be don’t just want to shame misfits but imprison, torture, even murder them. The choice of time period is as significant here as it always is on Mad Men. Climactic social change is afoot, and the Establishment is starting to panic. There are maybe a half-dozen ongoing subplots on Asylum. All are about repression—not just the private, individual repression of “impure” thoughts, as represented by Lange’s Sister Jude, a nun who wears a red negligee under her habit, but the systemic repression of then-taboo behavior. One asylum inmate (Chloë Sevigny) is there because her cheating boyfriend committed her for having retaliatory sex with an array of lovers and admitting she loved every minute of it. An interracial couple secretly marries in violation of an anti-miscegenation law, and then gets brutally separated by what could be an alien abduction or a kidnap-murder. James Cromwell’s Dr. Arthur Arden is the show’s stand-in for the patriarchy, a surgeon who delights in performing experiments on trussed-up patients, and who might secretly be the serial killer known as Bloody Face. Sarah Paulson is a nosy lesbian journalist who starts out trying to expose the asylum’s secrets but—thanks to panicked betrayal by her lover, a “respectable” schoolteacher—ends up trapped there.

As giddily naughty, vulgar, and demented as Asylum is, it’s a serious piece of work, and the product of a singular (if rarely neat) sensibility. I’m hopelessly in love with it at the moment, but don’t be surprised a few weeks from now when I declare that I’m done with it, or next year, when I write a piece about how I love it again. I really should rip the Band-Aid off my relationship with his shows, but I can’t bring myself to do it, because the only thing worse than Murphy at his worst is knowing that if you stop watching, you might be missing Murphy at his best. And in case you’re wondering, yes, I have watched his latest series, the Modern Family–esque sitcom The New Normal. I despised the first two episodes and swore I’d never watch again, but sure enough, as I type away on deadline, trying to finish this article, a friend e-mails to tell me I should give it another chance.

American Horror Story: Asylum, Wednesdays at 10 p.m., Fox.

Glee, Thursdays at 9 p.m., Fox.

*This article originally appeared in the November 5, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.