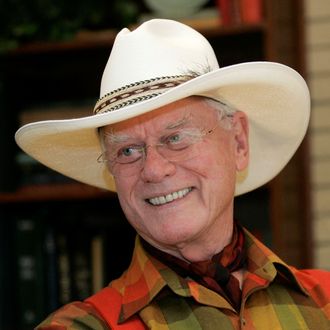

Larry Hagman, who died Friday of cancer at 81, wasn’t just a gifted actor. He was a great star who pulled off one of the most unlikely reinventions in American TV. Whether playing the befuddled Major Anthony “Tony” Nelson on I Dream of Jeannie or raising hell as J.R. Ewing on Dallas, there was always an alertness and joy in his acting, but the breadth of Hagman’s talent becomes undeniable when you put those key roles next to each other.

On Jeannie, a sprightly, casually sexist 1960s sitcom about an Air Force officer and his gal-Friday-in-a-bottle, Hagman was Cary Grant transformed into Ralph Bellamy by a fairy tale contrivance, disentangling himself from mishaps while preserving scraps of dignity. J.R. was as powerful as Nelson was powerless — a cartoonish prime-time version of a Shakespearean devil figure, treating Texas as an immense stage upon which he could mount any drama his greedy mind dreamed up. As J.R. pitted rival against rival and relative against relative, pausing to dress down inferiors and undress big-haired women, there was a dark wisdom in Hagman’s performance — a sense that J.R., like a Shakespearean bad guy, saw himself as both a dramatist and a character in the drama, and that he held the other characters in contempt because they lacked that awareness. He was the puppet master, and the rest of those idiots didn’t even know they had strings.

That the same actor could play a harmless, essentially decent goofball on a smash hit comedy, then return to prime time less than a decade later and inhabit such a loathsome yet charismatic antihero, was impressive at the time – the sort of trick that made other TV stars think, “I didn’t know you could do that!” and call their agents. As I wrote in my review of the TNT reboot of Dallas, “he pulled a Bryan Cranston before anyone had heard of Bryan Cranston.” Hagman’s innate likability made the transformation possible. It made us enjoy J.R. and live vicariously through the character even as we felt faintly ashamed for enjoying his wickedness. Hagman’s chokehold on the audience’s affection enabled him to negotiate a huge per-episode fee for Dallas and made him one of TV’s richest actors. Supposedly the 1980 “Who Shot J.R.?” cliffhanger — the conclusion of which made the cover of Time and earned the second highest rating for a scripted series episode after the 1983 M*A*S*H finale — was partly driven by CBS trying to scare Hagman into dropping his demands for more money. We all know how that turned out: J.R. lived, and Dallas ran ten more years with Hagman as its star.

Hagman played many roles before and after his run of hits in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The son of actress Mary Martin and lawyer Ben Hagman, Hagman was born in Ft. Worth, served in the Air Force during the Korean War, and did a year at Bard College before becoming a professional actor. After Jeannie, he starred in two short-lived sitcoms, NBC’s The Good Life (1971-72) and ABC’s Here We Go Again (1973). He had memorable supporting roles in films, including 1974’s Harry and Tonto (playing Oscar-winner Art Carney’s son) and 1978’s Superman: The Movie (as a sleazy general). But Dallas was his defining work, and after the series left the airwaves in 1991, Hagman played at least three more roles powered by the residual aura of J.R., in Oliver Stone’s 1995 epic Nixon, Mike Nichols’ 1998 adaptation of Primary Colors, and Ryan Murphy’s FX series Nip/Tuck.

In the former, Hagman played the film’s only purely figurative character: a mysterious Texan who seemed to represent the capitalist powers that secretly ran the country alongside the military-industrial complex. To fill a role that mysterious and chilling, Stone had to cast an actor who radiated menace, someone so strong that he could plausibly intimidate Anthony Hopkins as Nixon. What better choice than the man who played J.R.? Hagman’s Nip/Tuck character Burt Landau was like J.R. gone to seed: a rich venture capitalist who bought the plastic surgery clinic McNamara-Troy, got implants to replace the testicles he lost to cancer, forced Dr. Christian Troy to have sex with his young wife Michelle to help her achieve orgasm, and eventually suffered a stroke brought on by erection pills. Hagman’s Primary Colors character, Gov. Fred Picker, was basically a good guy: a well-liked former Florida governor, and the only man who could take the Democratic presidential nomination away from the film’s Bill Clinton-esque hero, Tennessee governor Jack Stanton (John Travolta). Hagman makes us believe that he could be an electrifyingly folksy politician, the kind of man that voters would follow into Hell, and that he would truly hate himself for letting drugs destroy his potential for greatness. In the film’s most haunting scene, Stanton confronts Picker with campaign research confirming that Picker once had a cocaine habit that destroyed his marriage, and that he had a casual gay affair (Picker describes it as “a coke thing”). Hagman plays the scene simply, giving Stanton credit for “doing the honorable thing” when in fact he’s forcing Picker to drop out of the race or be scandalized. The character is in the position of one of J.R.’s victims, a good man outflanked by a master manipulator. “You know, I was really so successful at everything I did,” Picker confesses. “Business, politics, hell, I could handle anything … except cocaine. Only I didn’t know that, because of cocaine!”

Hagman struggled with substance abuse himself. He was a heavy drinker and smoker throughout his adult life. He eventually recovered and quit alcohol and cigarettes (he became an anti-smoking activist in the ‘90s and appeared in “Great American Smoke-Out” ads), but years of hard living had taken their toll. In 1992 he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver and came out as a problem drinker. Three years later, doctors found a malignant tumor on his liver, and he had to have a transplant. Afterward, Hagman became an organ donation advocate and volunteered at a hospital to comfort cancer patients. Hagman was easily the best thing on the reboot. His advanced age (and wild old-man eyebrows) deepened the character. J.R. was worried about his legacy now, and his retinue of women was just for show – an expression of financial rather than sexual potency. Hagman seemed to draw on his own age and health problems as he acted the part. He moved more slowly now, conserving his energy like an old cobra who could only strike once a day. J.R. was still Richard III, but was turning into King Lear; that he was the only character who seemed to know this added a poignant dimension to his evil plots, and connected the new Dallas to the old.

The producers of the new Dallas, which returns for a second season in January, said Hagman had already shot six of a scheduled 15 episodes, and that the character will die on the show and be given a grand send-off. Hagman may have already contributed a key image to the funeral episode. “I know what I want on J.R.’s tombstone,” he said in a 1988 interview. “It should say: ‘Here lies upright citizen J.R. Ewing. This is the only deal he ever lost.’”