Saltz on the MoMAÔÇÖs Inventing Abstraction

Early-twentieth-century abstraction is artÔÇÖs version of EinsteinÔÇÖs Theory of Relativity. ItÔÇÖs the idea that changed everything everywhere: quickly, decisively, for good. In ÔÇ£Inventing Abstraction, 1910ÔÇô1925,ÔÇØ the Museum of Modern ArtÔÇÖs madly self-aggrandizing survey of abstract art made in Europe, America, and Russia, we see the massive energy release going on in that moment. Organized by Leah Dickerman, the show is jam-packed with over 350 works by 84 painters and sculptors, poets, composers, choreographers, and filmmakers. The sight of so much radical work is riveting.

Yet art of this kind still poses problems for general audiences. They look on it warily. Indeed, even we insiders sometimes donÔÇÖt get why certain abstraction isnÔÇÖt just fancy wallpaper or pretty arrangements of shape, line, and color. It can take a lifetime to understand not only why Kazimir MalevichÔÇÖs white square on a white groundÔÇöstill fissuring, still emitting aesthetic ideas todayÔÇöis great art but why itÔÇÖs a painting at all. ThatÔÇÖs the philosophical sundering going on in some of this work, the thrill built into abstraction. Insiders will go gaga here. But I wonder whether larger audiences will grasp the way this kind of art thrust itself to the fore in the West, coaxing artists to give up the incredible realism developed over centuries by the likes of Raphael, Caravaggio, Ingres, and David.

For 400 years, starting in what we now call Italy round 1414, a highly codified form of picture-making took hold in Europe. It was based rigidly on perspective, and all subject matter was soon depicted in the same perspectival space. Surfaces got smoothed out; traces of process all but disappeared. Thus came into being one of the greatest picture-making cultures of all time. By the nineteenth century, decadence was setting in. You could see it, painfully clearly, in the sea of stylistically similar salon paintings: frolicking children, middle-class life, society ladies, romantic views of nature and animals, and lots of voluptuous nude women seemingly worn out from masturbating. Constable, Corot, Courbet, the Impressionists, the Post-Impressionists, C├®zanne, and others loosened the pictorial stranglehold. Yet by the early-twentieth century their painterly perestroika was no longer enough. A total break had to happen. Even Cubism, as radical as it was, wasnÔÇÖt enough to do the trick: As the painter Robert Delaunay put it, ÔÇ£C├®zanne broke the fruit dish, and we should not glue it together again, as the Cubists do.ÔÇØ

Which brings us to the first work in ÔÇ£Inventing Abstraction.ÔÇØ This being MoMA, I donÔÇÖt have to tell you that itÔÇÖs by the museumÔÇÖs macho honcho Picasso. ItÔÇÖs Femme ├á la Mandoline, an intriguing, dusky-colored 1910 work with cubistic compartments, shapes, and slants. Apart from a curve that could be from a mandolin or a hint of hip, there are almost no defining real-world features. This is Picasso coming this close to pure abstraction. Then he blinks. ÔÇ£There is no abstract art,ÔÇØ he stated. ÔÇ£You must always start with something ÔǪ even if the canvas is greenÔÇöso what? In that case, the subject matter is greenness!ÔÇØ HeÔÇÖs right, of course. Even so, the rest of the show is dedicated to artists who didnÔÇÖt blink.

Some sights that follow overwhelm. A wall of nine 1915 Malevich paintings wows with its all-out commitment to form, shape, and color arranged in ways that will never look like intellectual wallpaper. Back up, so you see these punctuated by BrancusiÔÇÖs rough-hewn Endless Column, and youÔÇÖll witness astral geometric visions through some metaphysical Teutonic timberland. The sight of these two artists going for broke is unforgettable. As is the alcove of eleven Mondrians that lets us witness this Dutchman taking Cubism beyond the nth degree, transforming it into one of the most instantaneously recognizable and clear visual styles since the ancient EgyptiansÔÇÖ. Starting with a 1912 rendering of bowing trees, Mondrian moves through fields of waterlike marks to crosshatched grids of wavering space, all the way to pure geometry. Absorb yourself in his infinitely rendered edges; see how your inner eye perceives pings of light (visible, but not painted; theyÔÇÖre all in your retina and your mind) where MondrianÔÇÖs lines cross. This isnÔÇÖt just abstraction. This is the movement of visual elements, micron by micron, in ways not seen since Van Eyck.

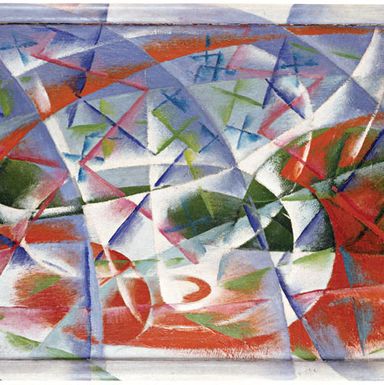

A large Picabia from 1912 is so deadpan, ironic, and visually aggressive that you see in it future artists like Polke, Kippenberger, and Oehlen. Not far from there, seven different-colored geometric shapes, each on a white ground, by Russian Ivan Kliun radiate calibration and nuanced surface, and point directly to artists like Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, and Robert Mangold. The British painters (Wyndham Lewis, David Bomberg, Lawrence Atkinson) all surprised me by looking better than IÔÇÖve ever seen them. TheyÔÇÖre still self-conscious to the core, contriving every effect, much as recent British artists do. Even the Futurists like Giacomo Balla and Francesco Cangiullo, whose cartoony ideas about movement can be annoying, look good confined to a small space in small numbers. Their posters and diagrams far outshine their paintings.

The show will still leave general audiences in the dark about why abstraction came into being. But careful observation reveals how powerful abstraction can be, how it is still a tool that circumvents language, disrupts identification, dissolves narrative, delays the crystallization of meaning, and becomes a reality unto itself. These days, abstraction is normal, not shocking, the expected thing in schools, galleries, and museums. Too many artists still ape the art in this show, throwing in Abstract Expressionism, post-minimalism, or surrealist twists and tics, adding things their teachers have told them about. Their work is as boring as it is derivative. The exciting news is that artists are doing away with purist cant, getting rid of academic dogma, dumping Clement GreenbergÔÇÖs rigid nonsense about ÔÇ£flatness.ÔÇØ Artists are polluting and expanding abstraction in fabulously impure ways, bending its armature into whole new configurations. And abstraction, old and new, can still leave us floored. These days, I am stunned by Uri AranÔÇÖs sculptures, which conjure the logic of imaginary maps with objects laid out on tabletops, and by the painter Lisa Beck, who hangs pairs of canvases in corners, one with a mirrored surface that reflects the other; somehow the parts meld, become a whole that seems to act as a telescope into unknown dimensions.

At MoMA, itÔÇÖs great that Dickerman allows masterpieces to share the stage with lesser-known works. She smartly puts stained glass, needlepoint, wood carving, posters, photos, and illustrated books on equal footing with painting and sculpture. For MoMA, which rarely mixes and matches media in its permanent collection, this is a big, praiseworthy step. Yet even with much to love, thereÔÇÖs something demented, even dangerous about this show. Only an institution this besotted with its own bellybutton would title a show ÔÇ£Inventing Abstraction, 1910ÔÇô1925.ÔÇØ Abstraction wasnÔÇÖt invented in the West in those years. Abstraction has been with us since the beginning. Westerners discovered it, or rediscovered it. In many cases, it soon became insular and overpurified. Consciously, conceptually, purposefully, fervently. Abstraction is there in the caves. ItÔÇÖs been practiced ever since, all over the world. All two-dimensional art is abstract, in that itÔÇÖs a representation of something in the world rather than the thing itself. Neolithic stone sculpture and Chinese scholar rocks are as abstract as BrancusiÔÇÖs Column and Vladimir TatlinÔÇÖs tower monument. Missing at MoMA are visionaries like Adolf W├Âlfli, whose manic abstraction can make Kandinsky look tame; George OhrÔÇÖs biomorphic ceramic configurations; Rudolf SteinerÔÇÖs cosmic diagrams; and Olga Rozanova, who was making Rothkos and Newmans of her own. What about Antoni Gaud├¡, whoÔÇÖs about as out-there abstract as it gets, on a giant scale? All would have dovetailed perfectly with the wild-style work here by Nijinsky. The American sculptor John Storrs is MIA. Ditto Hilma af Klint, who was making fantastically abstract paintings as early as 1906. The deeper you dig, the worse it gets. ThereÔÇÖs an empty gallery devoted to music by Stravinsky, Debussy, and others: Fine. But thereÔÇÖs no Scott Joplin! No Dixieland, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, or Jelly Roll Morton. All are as original and as ÔÇ£abstractÔÇØ as these Europeans.

Really, the title of MoMAÔÇÖs show could be ÔÇ£High Museum Abstraction: History Written by the Winners.ÔÇØ Or ÔÇ£White Abstraction.ÔÇØ On some level, this show is MoMA talking to itself, looking for ways around its ever-present deluded, limited narrative. If it doesnÔÇÖt open up this story line soon, MoMA will be doomed to examine the imagined logic of its beautiful ┬¡bellybutton, alone and forever.

Inventing Abstraction, 1910ÔÇô1925. Museum of Modern Art. Through April 15.

*This article originally appeared in the January 14, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

A view of Morgan RussellÔÇÖs Synchromy in Orange: To Form (1913ÔÇô14).

Photo: Christopher Anderson/ Magnum Photos/Christopher Anderson/ Magnum Photos

László Moholy-Nagy, Nickelplastik (1921)

Photo: Digital Image ? MoMA, N.Y.

Giacomo Balla, Velocità Astratta + Rumore (1913ÔÇô14)

Photo: Giacomo Balla/?? Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Veni...Giacomo Balla, Velocità Astratta + Rumore (1913ÔÇô14)

Photo: Giacomo Balla/?? Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

Gino Severini, Mare = Ballerina (1913)

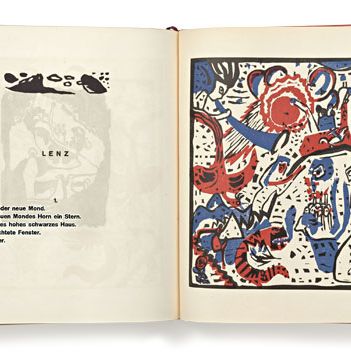

Vasily Kandinsky, Grosse Auferstehung, from Klänge (late 1912 or 1913)

Photo: Robert Gerhardt/Digital Image ? 2008 MoMA, N.Y.