Saltz: The MetÔÇÖs Matisse Exhibit Is Intoxicating, Possibly Dangerous

Midway through the Metropolitan Museum of ArtÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Matisse: In Search of True Painting,ÔÇØ I ran into the painter Alex Katz. He looked at me, agog, and said, ÔÇ£I thought I was going to faint when I saw these paintings.ÔÇØ He gestured at two Matisse still lifes from 1946. Already in a stunned state of my own, I followed his lead and gulped at the revolutionary pictorial power and radical color radiating off these two powerhouses, one dominated by a celestial red and an arrangement on a table. In the foreground were either a dog and cat chasing each other or a pair of animal-skin rugs.

Then I looked at the painting next to it. I saw the same still life depicted on the same table with the same vase, goblet, and fruit. But this version was totally different. Where the dog and cat were, thereÔÇÖs an ultraflat still life within the still life. ItÔÇÖs so categorically compressed that it looks less than two-┬¡dimensional ÔÇö maybe one-half-┬¡dimensional. I thought I, like Katz, might pass out.

What makes this show so ravishing is, improbably, that itÔÇÖs arranged like an art-history-class slideshow time line. Paintings from the same period hang in pairs and trios, according to subject matter and theme. The revelations produced by this back-and-forth viewing make these 49 paintings blossom anew ÔÇö this after a lifetime of being overwhelmed by the swarming multiplicity of MatisseÔÇÖs paintings. At the Met I saw new optical fatness, freshness, experimentation; hidden levels of MatisseÔÇÖs ever-unfolding opulence. ÔÇ£In Search of True PaintingÔÇØ lifts up an always-present veil of reticence and perplexity in MatisseÔÇÖs art. His decisions come into focus, and their effects are shocking.

The show starts with several jolts. In two still lifes from 1899, we can watch the late-┬¡blooming 30-year-old assimilate Impressionism in one painting. In the second 1899 still life, he moves beyond it, grasping C├®zanneÔÇÖs flattened planes and shards of space. Through these two works Matisse travels a painterly lifetime. In a pair of 1904 landscapes, he turns himself into a great Post-Impressionist, a couple of decades after the fact. Then come two sailor portraits from 1906. One has Pointillist dots and daubs. Disorganized, patchy, impatient, this is an artist saying good-bye forever to following other peopleÔÇÖs isms. The other sailor, done the same month, is so visually riveting I surmise it could hang next to Vel├ízquezÔÇÖs epic portrait of Leo X and survive. The sailor undulates in space. HeÔÇÖs a rag doll, a cutout puppet, something from folk ceramics, an almond-eyed alien. His arcing left leg crosses in front of the right, then somehow bends behind it again. The torque of the body is almost Egyptian: in profile and dead-on at the same time. Matisse was on fire.

By this point it seemed like the back of my head was, too. Having seen only a handful of pairings, IÔÇÖd slipped into a chasm: I saw myself seeing Matisse, getting glimpses of how intentional each decision was, feeling very close to his pictorial intelligence, almost merging with it. Giddy, I floated toward a wall of four paintings of Notre Dame as seen from MatisseÔÇÖs Seine-side studio. The pictures start out journalistic, then become sketchy, then depict passing time, and go all the way to the timeless abstract majesty of MoMAÔÇÖs great masterpiece from this series, the blue almost-monochrome one with black lines and churchlike proportions. IÔÇÖve seen this picture hundreds of times. Never like this.

I looked around. A tiny detail in another masterpiece, Le Luxe II, filled my vision. Matisse renders a batherÔÇÖs right arm so that it is behind and in front of her hip simultaneously. That shouldnÔÇÖt be possible in paint, but there it is. In the same gallery are two 1914 studio interiors with goldfish: As I sized up their solidity and density, I was pulled in by the angle of the windowsill, relishing the receding space. Before I recovered, the gigantic-seeming painting next to it preempted my vision. ItÔÇÖs the same scene from a different angle. The goldfish are directly in front of the window. Everything flattens and breaks into striated geometric spaces. The entire left-hand part of the picture is dominated by those hot tangerine goldfish. A detail lurches into sight: The right side of the bowl turns into a world unto itself. Matisse has taken some tool and scratched and scribbled into the paint. The gestures turn the goldfish bowl solid, transparent, and incandescent all at once. I think I am seeing what is there and what is not, the quiver of the lack of a real visual edge between a glass of clear water and real space.

By this time, there was only one thing left to do. I left the show and returned on other days. If I hadnÔÇÖt, I donÔÇÖt think IÔÇÖd have gotten out of there on my own. Matisse is a beast.

Matisse: In Search of True Painting, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Through March 17.

*This article originally appeared in the February 4, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

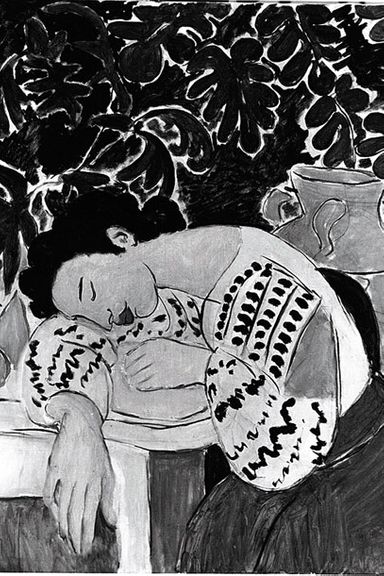

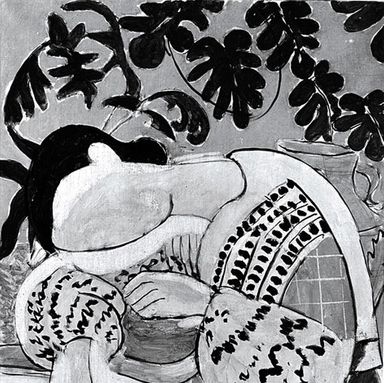

January 7, 1940

January 8

January 9

January 11

January 13

January 17

January 18

February 13

March 7

March 8

March 9

September 16

September 17

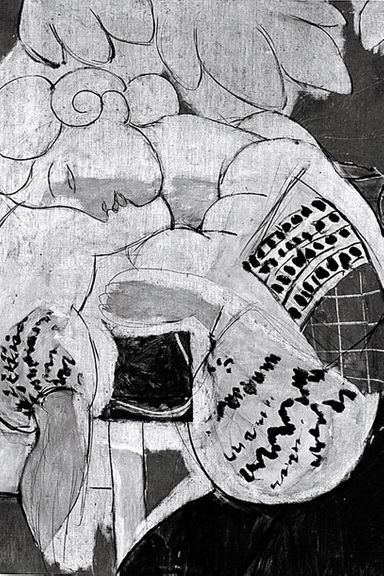

The completed painting, September 1940