We need a name for them, that subset of literary protagonists who are appealing despite being appalling. I do not mean the mere anti-hero. In literature as in life, anti-heroes outnumber outright scoundrels ten thousand to oneÔÇöespecially these days, when our shelves sag under the weight of intentionally apathetic main characters. Life is full of banal disappointments, and these guys (for they are almost always guys) suffer them, zhlubbily. Separated, divorced, overweight, underemployed, aimless, faithless, wifeless, they are epic poets of pathetic heterosexuality, contemporary literatureÔÇÖs counterpart to the more dejected corners of country music. I like some of these characters, unprepossessing though they are, but to my mind, the best protagonists often do the worst things. Indeed, the more felonious, the better.

What a relief, thenÔÇöwhat a perverse pleasureÔÇöto watch as Eric Kennedy, the narrator of a new novel by Amity Gaige, plunges from the droopy former category (for he, too, is slouchy and adrift, underemployed and separated) into the delectable latter one. That new novel is called SchroderÔÇöwhich is also, without the italics, EricÔÇÖs real last name. Born Erik Schroder in East Berlin in the seventies, he is smuggled across the wall at age 5 by his father, who tells Customs agents that EricÔÇÖs mother is dead. She isnÔÇÖt, but she might as well be; the boy never sees her again. Instead, he and his father move to a working-class neighborhood of Boston, where they utterly fail to fit in.

Then comes the fateful transformation. At age 14, in an application to summer camp, Erik Schroder spontaneously reinvents himself as Eric Kennedy: accent-less, all-American, born and raised in the made-up Cape Cod town of Twelve Hills, ÔÇ£a stoneÔÇÖs throw from Hyannis Port.ÔÇØ So thoroughly does Schroder embrace this alter ego that, over time, he suppresses virtually all traces of his past, internally as well as externally. It is Eric Kennedy who attends college, falls in love, marries, and fathers a child. And it is Eric Kennedy who loses his job in real estate (for Schroder takes place around the dread year 2008); Eric Kennedy whose wife demands a separation; Eric Kennedy who manages, through some combination of denial and ineptitude, to sign away almost all his parental rights.

Thus does Gaige wind the gears of her plot. A onetime stay-at-home dad, Kennedy now sees his daughter, Meadow, every other weekend and for a few hours on Wednesdays. Soon enough, the time between her visits becomes a blur of Canadian Club and grief. But that grief has an ominous bass note, a notably non-American schhh rolling through it: Kennedy cannot take his estranged wife to court, because ÔÇ£KennedyÔÇØ does not exist. And so, during one of MeadowÔÇÖs visits, he buckles her into the backseat of his car and drives away: out of New York, across state lines, across all kinds of linesÔÇöanother small nation shearing in half, another father escaping, or absconding, with his child.

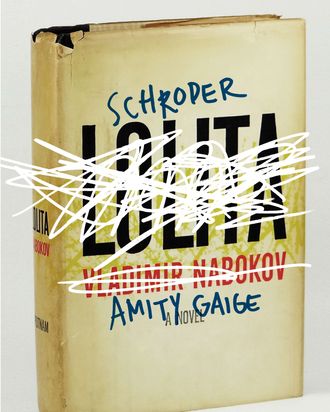

There is, lurking behind Kennedy, another felon-narrator, perhaps the most famous one in all of literature: Humbert Humbert, the odious, marvelous lech of Lolita. NabokovÔÇÖs shadow on the page is as recognizable as HitchcockÔÇÖs on the screen, and it shows up all over Schroder. The precocious Meadow tells a stranger that she wants to be a lepidopterist (as Nabokov was); a repentant Kennedy covers four solid pages with the words ÔÇ£I let you down.ÔÇØ (Humbert Humbert: ÔÇ£Repeat till the page is full, printer.ÔÇØ)

Those are just Easter eggs, there for the fun of finding them. But SchroderÔÇÖs homage to Lolita is so complete as to be fractal: You can see it at every scale of resolution, from cameo to structure to plot to theme. Both books are presented as confessions, written while the narrators are in custody for crimes concerning their daughters. (Or stepdaughter, in HumbertÔÇÖs case.) Both books begin by scrolling back to the past, where those narrators suffer early traumas that prefigure their later crimes. (Pedophile-to-be Humbert Humbert loses his childhood love to typhus; kidnapper-to-be Kennedy is wrenched away from his mother.) Both books then proceed as road trips. Leaving his adopted hometown of Albany behind, Kennedy takes Meadow for a dip in Lake George, crosses the Adirondacks, stretches at truck stops, lets the backseat of the car fill up with candy wrappers and cans of Mountain Dew.

NabokovÔÇÖs recurring word for this in ┬¡Lolita is viatic: of the via, the way. That is, implicitly, the American way, which is largely what both these books are about: our relationship to foreigners and theirs to us, our national fascination with self-┬¡reinvention, and, above all, the nature of our moral infrastructureÔÇöwhich, like our physical one, conduces to speed, liberty, anonymity, easy entrances and exits, the slate-cleaning promise of elsewhere. Hence those road trips, our nationÔÇÖs tragicomically misguided metaphor for freedom: windows down, radio blasting, the last communal tie flung out the window like a cigarette butt or a speeding ticket, the whole thrilling joyride guaranteed to end in silly glory or spectacular wreck. I wonÔÇÖt divulge the details, but is it any surprise that both books endÔÇöor anyway, their father-┬¡daughter journeys endÔÇöin hospitals?

It is not, but some other things here are surprising. First: that a novelist as understated as Gaige would have the chutzpah to steal in its entirety what is arguably the most beloved, most reviled, most recognizable book in the entire corpus of English-┬¡language literature. Second: that from such familiar parts could be built such an unfamiliar storyÔÇöone that simultaneously honors, updates, and rejects its original. Third: that, until this book came out, I had never heard of Gaige.

ItÔÇÖs a mark of how good Schroder is that, upon finishing it, I immediately went out and read the rest of her work. What I learned, among other things: Gaige has a thing for youngish male protagonists at risk of losing their minds and their marriages. Her two previous novels each star one such proto-Schroder. Both books are excellent, and both are subtly but deeply weird. The first, O My Darling, features an emotionally haunted couple who live in what may or may not be an actually haunted house. The second, The Folded World, features another young couple, two psychiatric patients, and a clairvoyant grandmother. Gaige is interested in the boundaries between thingsÔÇösanity and delusion, morality and immorality, self and worldÔÇöand she manifests that interest here by blurring, as Poe did, the line between ghost story and psychosis.

Schroder retains this interest in boundaries but sheds the faint cirrus layer of spookiness. It also represents a marked stylistic departure. In her earlier novels, GaigeÔÇÖs language was plain and specific, clear the way ghosts are clear: transparent, but introducing a faint, unnerving distortion between us and the world. In ┬¡Schroder, channeling the voice of Kennedy, she becomes twitchier, funnier, more mobile of register, and, for good and ill, possessed of a host of familiar postmodern reflexes. KennedyÔÇÖs confession includes a lot of footnotes, a brief screenplay, and occasional diversions into ÔÇ£pausology,ÔÇØ his long-┬¡standing, ┬¡nowhere-going project on the history, theory, and typology of silences. These irked me at first, then grew on me, chiefly because they seem like exactly the kind of low-┬¡hanging literary and intellectual habits someone like Kennedy could reach.

Still, even when she cranks up her own dial, Gaige is nothing like the extravagant stylist behind LolitaÔÇöpartly because no one is, and partly because it does not suit her purpose here. She is interested in moral ambiguity, and moral ambiguity is not terrain you can explore in the key of Nabokov. Humbert Humbert is, to borrow this magazineÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Approval MatrixÔÇØ for a moment, highbrow-despicable. A murderer with a fancy prose style, as Nabokov memorably characterized him, he is both ten times more abhorrent and ten times more glee-inducing than Kennedy (or anyone) could ever be. Thanks to this extremity, and despite having occasioned decades of pious hand-wringing, he presents us with precisely zero moral conflict: No one, not even the man himself, thinks his behavior is anything short of atrocious. True, there is a clash between our ethical reaction to his tale (horrifying) and our aesthetic one (hot damn), but so what? It is perfectly possible, and perfectly consistent, to revile someone on the one axis and admire him on the other. I happen to think Antonin Scalia has a fancy prose style, too.

Kennedy, by contrast, does create a moral conflict for us; we can never quite work out what we think of him, even though the debit column is damning. From the get-go, we know that he has lied about his identity and abducted his daughter. And once hes on the road, detached from society and routine and whatever else moors us to morality, his judgment unravels even further. He takes Meadow to a bar in the middle of the day so he can drink whiskey and fake a phone call to her mother. He has sex with a stranger while she sleeps alone next door. And then there is the moment when  well, lets put it this way: Whatever you think of Humbert Humbert, at least he never tried to stuff Lolita in the trunk.

My margin note next to that scene reads, in its entirety, ÔÇ£ACK!ÔÇØ Yet what makes ┬¡Schroder so good is that, by the time we get there, our horror is counterpoised by a terrible understanding. WeÔÇÖve seen the internal logic behind the outrageous decisions (how would you get your undocumented 6-year-old into Canada?); and, more important, weÔÇÖve seen the tenderness. Kennedy hefts Meadow on his shoulders for an imaginary camel race, delights in the happy solemnity with which she rides a merry-go-round, listens with seriousness to her ideas about herself and the world.

And something else modulates our moral response here, too. In the half-century between Lolita and Schroder, American ideas about mothers, fathers, and parenting have shifted radically, and the general consensus seems to be that we are currently in a kind of lose-lose interregnum. White middle-class women are empowered-slash-expected to be everythingÔÇömoms, sex bombs, CFOs, triathletesÔÇöwhile still getting less pay for their work, less respect for their parenting, and vastly more flak for any perceived lapses in the condition of their kids, bodies, or homes. Their male counterparts, meanwhile, can no longer count on a steady climb up a respected career ladder, nor even on landing a decent job. And although they are now expected to help out with housework and child-┬¡rearing, the rules governing ideal conduct in those domains are still largely established and maintained by women.

That is the sociocultural minefield on which KennedyÔÇÖs marriage explodes. ÔÇ£An elusive gold standard, a goddamned miracleÔÇØ: ThatÔÇÖs him describing a happy childhood, but he might as well be talking about todayÔÇÖs other ever-moving target, good parenting. There is a fine, smart slide, in ┬¡Schroder, from behavior KennedyÔÇÖs wife deems inappropriate to behavior the police deem inappropriate. Consider: If your daughter expresses curiosity about a molding tangerine, would it constitute an acceptable at-home science experiment to watch over it together for a few weeks while it rots? Yes? Well, then: Is it acceptable to follow up by studying a decaying fox in the family backyard? Dad thinks yes, Mom thinks no, and his assessment of the conflict is funny, poignant, and damning to them both.

Shifting gender roles, the perils of contemporary parenting, the confusion and acrimony surrounding divorce: These are important subjects, obviously. But they are not intrinsically promising ones for fiction. A thousand books will be published this month with approximately the following plotline: ÔÇ£Unforeseen tensions erupt and important new truths emerge when a once-happy relationship begins to fray.ÔÇØ Forgive me, but 999 of them will be boring. GaigeÔÇÖs stroke of brilliance was to plant, in this most overfarmed of soil, literatureÔÇÖs most over-the-top tale. ÔÇ£Unforeseen tensions erupt and important new truths emerge when a middle-aged man kidnaps a young girl and goes for a romp around America.ÔÇØ ThatÔÇÖs a story. In fact, with the publication of Schroder, it is two stories.

History always happens twice, Marx famously opined: first as tragedy, then as farce. Gaige reverses the trick, bending NabokovÔÇÖs extravagant farce toward quiet tragedy. Appropriating one of the least restrained novels in all of literature, she somehow creates from it an understated and emotionally unsettling tale. My only regret is that, in the end, she pulls her punch. Lolita, in its final section, plunges into blatant madcappery, complete with the worldÔÇÖs stagiest murder scene. Gaige, who has transposed NabokovÔÇÖs tale into a lower key, cannot logically follow him there, and never quite figures out where else to turn.

Still, she has my admirationÔÇöand also my sympathy, because I, too, find myself unsure what to say in the end about ┬¡Schroder: a novel that is better than most, about a man who is worse than most. As a rule, it is easier to deal with the Lolitas and the Humberts of the world, in their fabulous or ghastly extremity. But true extremity, unlike true extremism, is rare in life. That holds across all domains, moral, aesthetic, and otherwise.

And that is what Gaige gets right. Kennedy belongs, as I began by saying, to the relatively small category of truly bad-news protagonists, entire actionable rungs down the ladder from your average Beleaguered Dude. And yet his presence there always seems contingent, his badness provisional. He confounds our moral judgment, not just because he is sympathetic or deluded or because his crimes are modest and strange, but becauseÔÇöand this is the crucial pointÔÇöin real life and the literature that reflects it, genuine moral judgment should almost always be confounding. We know there is a line out there somewhere. We know it is to the right of the tangerine and to the left of the trunk of the car. But it is hard to say where exactly it falls, or what finally impels someone to cross it, or how much misbehavior is inevitable and how much is determined by the chance twists of, as Humbert Humbert was fond of calling it, McFate.

That ambiguity is what differentiates Schroder from Lolita. Humbert Humbert is a Bad Man Who Did Things; Kennedy is a man who did bad things. As roguish protagonists go, he loses something in the bargain. He isnÔÇÖt extravagant like Humbert or ideological like Raskolnikov or mythic like King Lear. But he gains, too: among other things, our sympathy.

Schroder by Amity Gaige; Twelve; 272 pages; $21.99.

*This article originally appeared in the February 18, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.