Questlove’s Weeklong Master Class on the Gospel of Prince

Editor’s note: This piece originally ran in March 2013.

Questlove is in a large dressing room backstage at Carnegie Hall, getting his Afro picked out before going onstage to lead a concert honoring the music of his all-time favorite recording artist, Prince. His mother is sitting beside him, beaming at her boy. Back when Quest, now the Roots drummer and Jimmy Fallon bandleader, was a teenager, she and his father only listened to Christian radio and behaved like “the black Ned and Maude Flanders,” he writes in his upcoming memoir, Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove. When she found Prince records in his room, she would throw them out. “When Prince’s 1999 came out,” he writes, “it touched off a saga that lasted half a decade. I would say, conservatively, that I purchased that record eight times between 1982, when it first came out, and 1987, when I stopped getting on punishment for having it.”

The Carnegie Hall concert falls in the middle of a sort of ad hoc Prince festival in Questlove’s life. He hosted Prince March 1 on Fallon for a performance of “Screwdriver,” one of several great new songs (Prince may be preparing the release of a new album, and has also sent a new theme to his friend Tamron Hall’s MSNBC NewsNation). Then, the following Wednesday, came a dress rehearsal for the Carnegie show at City Winery, which felt like a full-on concert in an unlikely space, with almost everybody scheduled for the Carnegie show hanging backstage, swapping Prince stories as Quest sat behind the drum kit as bandleader. The day after Carnegie Hall, in Quest’s Friday NYU class “Topics in Recorded Music: Classic Albums,” he would deconstruct Dirty Mind with his students—talking through the three-hour seminar about how the album challenged the nature of funk while borrowing from porn. Then, Saturday, the professor would fly to Minneapolis to play with members of the Revolution in an annual benefit concert.

If Prince is a musical god, then Questlove has made himself into the Pope of Princeland. And tonight he has assembled an august conclave to sing his praises in a building hallowed as a church. Only Pope Questo could summon cardinals like D’Angelo, Elvis Costello, Chris Rock, Wendy Melvoin, Susannah Melvoin, Sandra Bernhard, Fred Armisen, and Maya Rudolph. “I wanted to make sure it was balanced among people I knew could stretch the bounds of the artistic envelope,” he says. “People I knew would be open to interpreting the songs.” People with what he called a “high Purple IQ.”

“Prince is probably the only artist who got to live the dream of constant innovation,” Quest told me in an interview for my new book about Prince, I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became an Icon. “He knew the balance between innovation and America’s digestive system. He’s the only artist who was able to, basically, feed babies the most elaborate of foods that you would never give a child and know exactly how to break down the portions so they could digest it. I mean, ‘When Doves Cry’ is probably the most radical song of the first five years of the eighties, because there’s no bass. I heard the version of ‘Doves Cry’ with a bass line—it wouldn’t have grabbed me. Without bass it had a desperate, cold feeling to it. It made you concentrate on his voice. With the bass line, the song was cool. Without it, it was astounding.”

But “Sister” may be the Prince song Questlove has thought about the most. It’s like the creation story for a superhero: My hypersexual older sister turned me out and made me into the hypersexual creature I am today. This is so whether or not you believe it’s a true story. The man who may or may not have been seduced by his loose older sister went on to become the King of Eighties Porn Chic, a cultural climate in which Prince and his quasi-biographical film Purple Rain fit perfectly—it’s like a soft-core porno set in the world of nightclubs. Pauline Kael wrote of the performance, “He knows how he wants to appear—like Dionysus crossed with a convent girl on her first bender.”

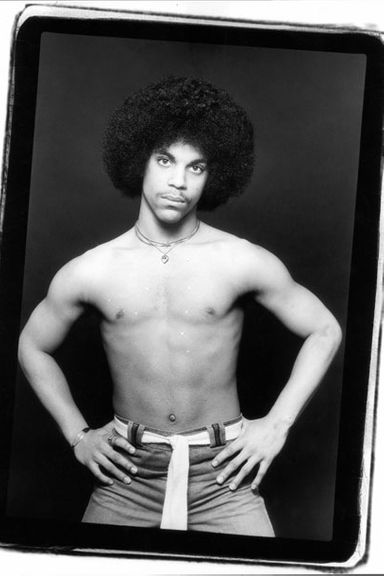

That gender bending wasn’t just for the stage. Those who know about Prince in bed know he was not afraid of a gender twoness. He loved women so much he sometimes mirrored femininity. A woman who had sex with Prince said, “He was the most patient man I’ve ever been with. And the most complicated in terms of being in bed with. The most sensitive, the most androgynous, the most balance of male-female energy. He was the closest thing that I’d had to having a woman.” That particular sort of carnality was always in full view onstage. Rarely had black sexuality been presented in such a raw, rough, wild, bi-gendered form as it was in the body and persona of Prince. In a hypersexual era, Prince made Hugh Hefner look like a slowpoke and Dr. Ruth Westheimer like a freshman.

White America has long viewed black sexuality with fear and fascination, certain that blacks are better endowed, more sexual, having more sex and having it with more abandon—as James Baldwin famously wrote, “To be an American Negro male is also to be a kind of walking phallic symbol.” Prince takes that to the nth degree, but he worships women so much that in his sex-story songs he’s less a devastating Casanova than a man being picked up by female aggressors whose sexuality he fights to keep up with.

“Black male sexuality is always going to be a threat in America,” Quest says. “And Prince came along at the right time. America still had post-Mandingo dreams, no matter how it looked, which really weren’t getting met by Michael Jackson. I remember a lot of interviews when Prince started catching on where they asked people, ‘Why do you like Prince?,’ and they said, ‘Well, Michael Jackson’s cool, but Prince gives us more sex.’ ” He chose that role consciously. Dez Dickerson, who played guitar in the earliest iterations of the Revolution, recalls an early sit-down. “Everybody in this band is going to have a distinct personality and identity,” Prince said. “I’m going to portray pure sex.”

“Cats had to fit with the look he wanted, not the sound,” Questlove says. “He didn’t pick the best players; he picked people who fit with his multicultural vision. He wanted an updated Sly and the Family Stone thing.” He remembers advice an older musician gave him when Quest was a kid. “You have to make [your band] look like America to make it in America. Then you won’t have to do this Chitlin’ Circuit bullshit. Maybe you’ll get farther than we did.”

The big-tent concert Quest built in tribute wasn’t just about Prince lovers regurgitating the familiar. “I didn’t want them to climb mountains they couldn’t climb, because his fan base is very guarded,” he said. “I felt it was wise to approach his songbook from an obscure level, so it’s artists interpreting songs so they’ll have a fair chance with the audience.” The show featured some hits, like the Waterboys doing “Purple Rain” and Sandra Bernhard doing “Little Red Corvette,” but also great songs that weren’t hits, like Elvis Costello doing the unreleased track “Moonbeam Levels,” the Blind Boys of Alabama doing “The Cross,” and Bilal doing “Sister” as a punk-inflected, raw, nasty thing filtered through his devastating falsetto—according to many, including this writer, the high point of the night.

At the end of the show, after a stunning, high-energy finale—D’Angelo leading everyone else on the bill through “1999”—Quest is back in his dressing room, again with his mother at his side, this time getting his hair cornrowed. He should be celebrating, but he cannot help but nitpick. “I hope one day to be good enough to play Prince’s music and not be constantly like, Oh damn, I screwed that up.”

*This article originally appeared in the March 25, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

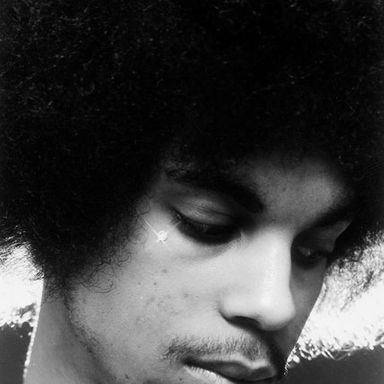

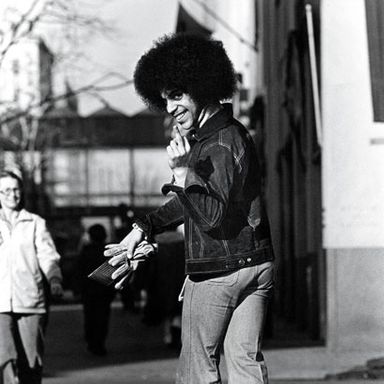

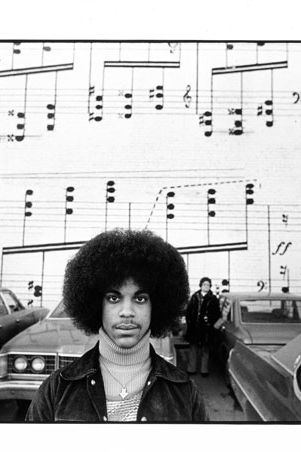

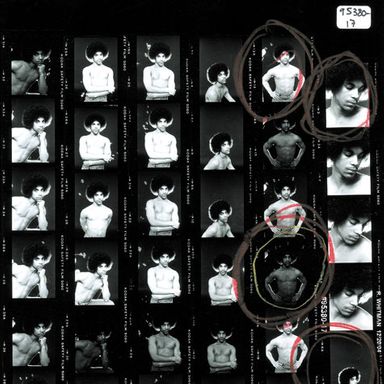

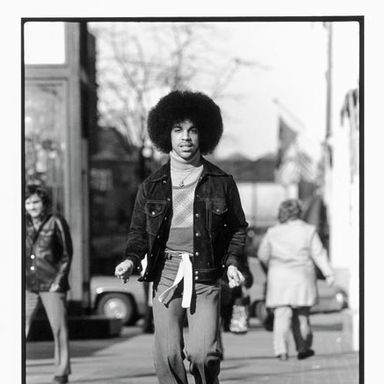

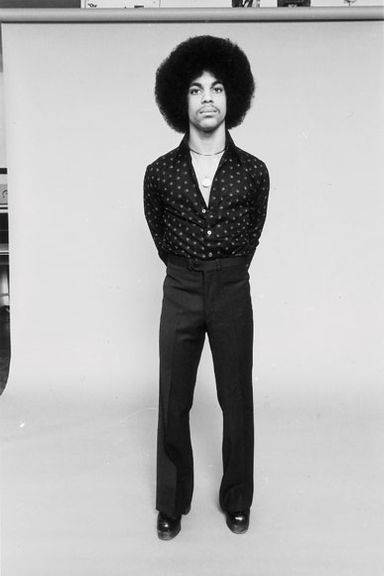

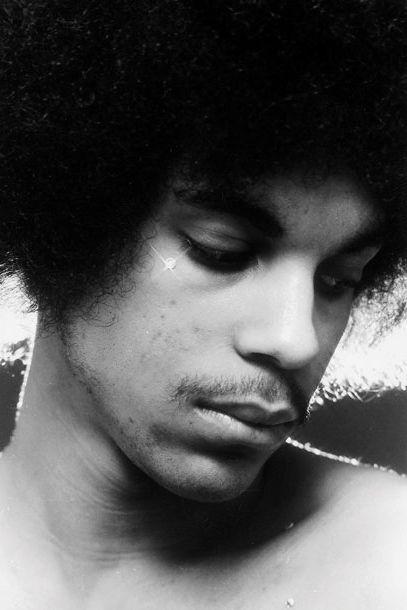

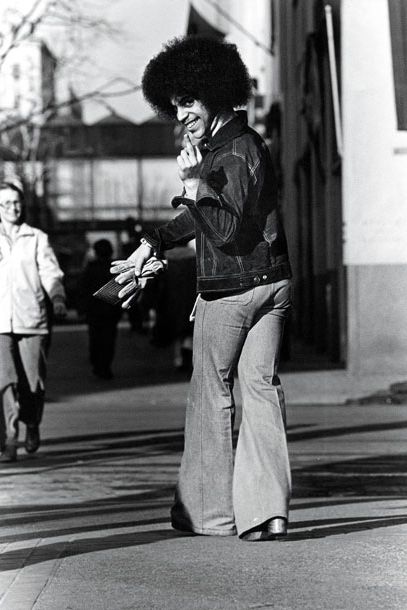

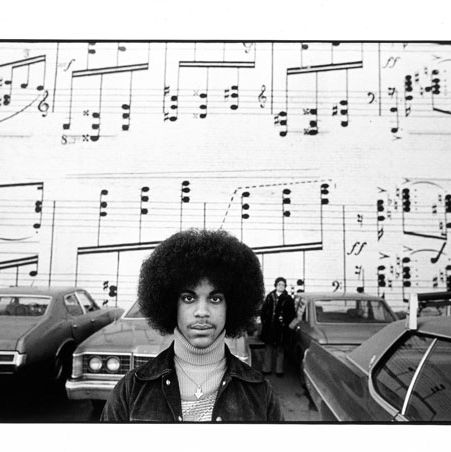

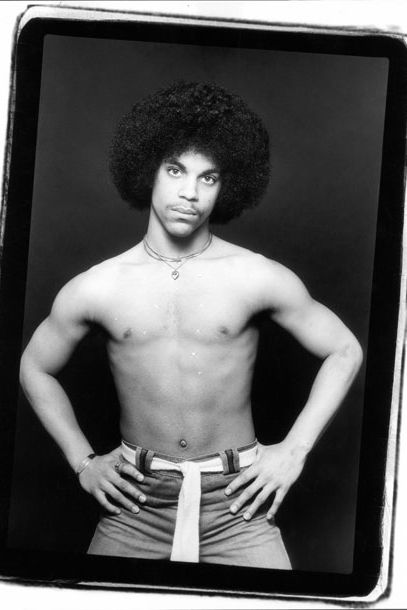

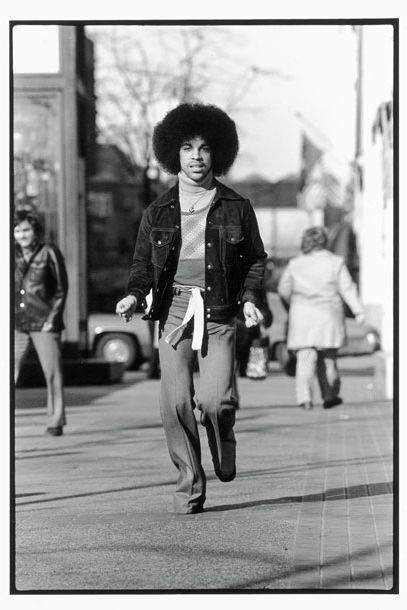

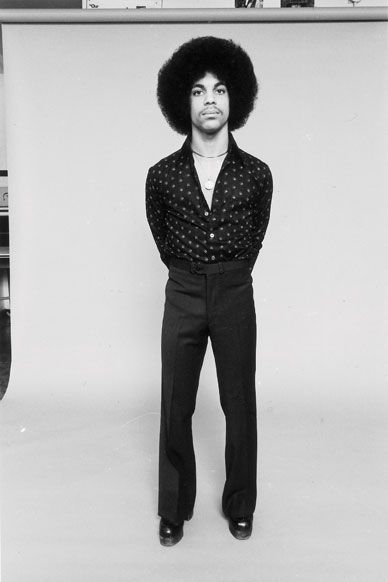

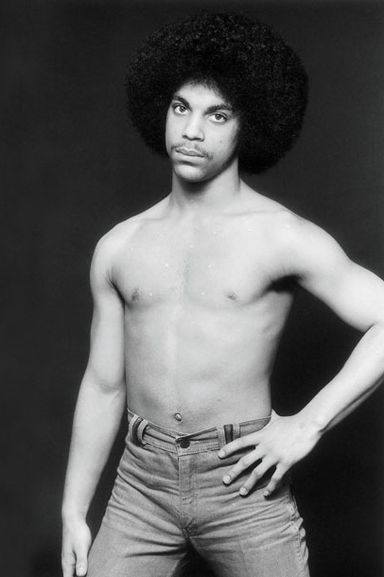

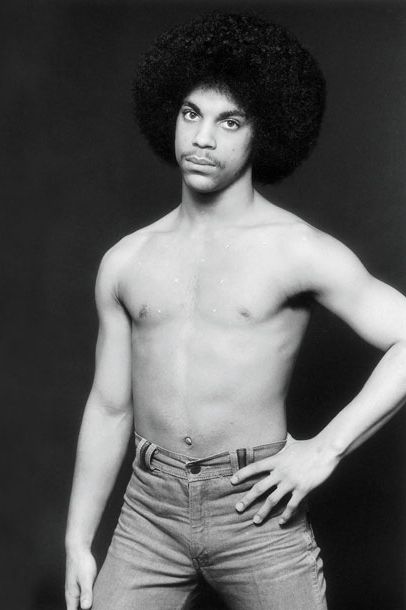

Click through the slideshow to see eight previously unpublished images of a 19-year-old Prince.

These previously unpublished photographs of a 19-year-old Prince were taken in Minneapolis just before his 1978 debut, when the singer was just beginn...

These previously unpublished photographs of a 19-year-old Prince were taken in Minneapolis just before his 1978 debut, when the singer was just beginning to reinvent himself as a sex-crazy trickster showman.