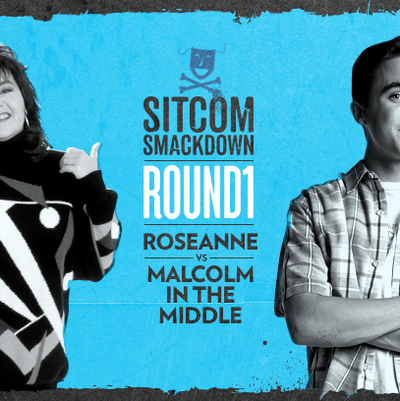

Vulture is holding the ultimate Sitcom Smackdown to determine the greatest TV comedy of the past 30 years. Each day, a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 18. Today’s battle: Vulture’s Margaret Lyons adjudicates between two struggling-family greats, Roseanne and Malcolm in the Middle. Make sure to head over to Facebook to vote in our Readers Bracket. We also invite tweeted opinions with the #sitcomsmackdown hashtag.

Working-class families with lusty parents and squabbling siblings, flanked by a bunch of oddballs and operating with a gleeful antagonism towards one another. When I sat down to evaluate Malcolm in the Middle and Roseanne, I thought the shows had a lot in common, and that their similarities would make picking one not moot exactly, but sort of futile. Aren’t these shows scratching the same itch?

They are not.

Both are excellent sitcoms that I loved deeply when they first aired — shows I watched repeatedly, related to, and saw myself in. But Malcolm exists in this other, cartoony world, and the show goes to great lengths to situate the viewer there, to acclimate us to its strange environment. Roseanne is very much in and of this world. Malcolm’s a telescope. Roseanne is a mirror.

Family sitcoms often rely on an undercurrent of haplessness, of at least one of the parents being or seeming incompetent, out of his or her element. Sometimes it’s used to great effect (Everybody Loves Raymond), but more often than not it’s overused (Modern Family being the most popular current example). But Roseanne and Dan Conner on Roseanne and Malcolm’s Lois and Hal (who never get a last name) avoid that cliché entirely. They are really good parents: stable, consistent, and incredibly present in their children’s lives. However much they scold or scream or feel exasperated with each other or their kids, there’s never bitterness or a lack of love. Most episodes of both shows include the families sitting down to an honest-to-God family dinner. And even if the meal ends in a food fight or someone stomping off, the effect is deeply comforting. That’s how those meals are in real life. We stomp because we love. Or rather, we can stomp because we are loved.

That realism defines Roseanne. When the show — created by and starring stand-up comedian Roseanne Barr — launched in 1988, it was on opposite Matlock. Think about how dated Matlock seems right now: Doesn’t that seem like a show title you’d find scrawled on the side of an old box of cracked VHS tapes? Yet Roseanne is shockingly timeless. There are almost no pop culture references, and other than scrunchies and non-cordless landlines, the show never seems to indicate what year it is. Part of that’s because credible emotional choices and a lack of sentimentality know no era. Dan, Roseanne, and their three kids, Becky, Darlene, and DJ, are distinctly drawn comic characters who retain a full range of human emotions. Roseanne’s sister Jackie could have been just a flighty busybody or an anxious mess, but like everyone else on the show, she contains multitudes.

At this point, everyone knows the set was often a nightmare, but you can’t tell from the first five seasons, which are pretty much flawless. (The strain begins to show in season seven, when Roseanne gets pregnant, and seasons eight and nine should probably be ignored completely.) Yet during its stellar run, Barr, John Goodman (Dan), and Laurie Metcalf (Jackie) all won Emmys, but the show never did. Can we see in this a microcosm of class prejudice? Oh friends, this is America: Everything is a microcosm of class prejudice.

Malcolm was even more under-appreciated. Cloris Leachman (Grandma Ida) was the only cast member to win an Emmy (Jane Kaczmarek, who played Lois, was robbed!), and creator Linwood Boomer never got the props he deserved. Somehow The Office and Arrested Development receive the credit for ushering in the era of single-camera comedies, even though Malcolm predates them. The fourth-wall-breaking asides of the show’s titular character — the family’s genius third son — and the show’s deep affection for strangeness make it seem like the clear precursor to Parks and Recreation. When Bryan Cranston’s Hal blissfully roller-dances around a playground, or Lois one-ups an army officer with her knowledge of psychological warfare, the show has all the whimsy and precision of 30 Rock. Malcolm was able to gobble up genre satire and coming-of-age cliches and metabolize them through its peculiar system of distorted, borderline grotesque, yet utterly joyous style. Like Roseanne, later seasons weren’t as good — not necessarily because of, but certainly coinciding with, the addition of a new baby. Ugh, babies! Is there nothing they can’t ruin?

For the purposes of this bracket, we’ve been asked to think about the shows at their best — and there’s no joy for me in re-watching subpar episodes. Most fans consider “Bowling” to be Malcolm’s greatest episode, and it is great. It’s told in split narratives, bouncing between what happens when Lois takes Malcolm and older brother Reese bowling, and what happens when Hal takes them. Each outing is disastrous in its own way, but Lois’s timeline climaxes in one of TV’s great moments of adolescent frustration and ineptitude, with Malcolm melting down after a little too much prodding.

But “Bowling” isn’t my number one. That would be “Water Park.” (I’m also partial to season four’s “Boys at the Ranch.” Ah, Francis.) “Water” is the season one finale, in which youngest brother Dewey is forced to stay home from the family vacation with his babysitter, the late, great Bea Arthur. At first she finds him grating, but when they’re sorting buttons — “first by number of holes” — the two discover they share favorite and least favorite buttons. (Dewey “saves” his in his mouth.) This somehow builds to the two doing an elaborate dance number to ABBA’s “Fernando.” Immediately afterwards, an ambulance takes Arthur’s character away, and she’s never heard from again.

In that little dance routine is everything Malcolm stands for. The idea that there is no bliss greater than a lack of shame. That self-consciousness is a curse, and self-possession a blessing. Your parents and brothers may embarrass you (which they almost certainly will as members navigate childhood, teenhood, and adulthood), and the world outside may judge you harshly for going against the grain, but you can drop the act when you’re around your family. Shave your back in the kitchen. Write a symphony while you’re in middle school. Find a way to hitchhike back from Afghanistan. You’ll never be more at home than you are at, er, home.

Roseanne doesn’t operate in nearly as shame-based a world. Roseanne at work is Roseanne at home is Roseanne out on the town: Loud, opinionated, sometimes unkind, but always down to earth and funny as hell. As image-conscious as Becky is in early seasons, or as panicky as Jackie tends to be, they are their real selves all the time.

Picking a favorite episode of Roseanne was harder for me than picking a favorite Malcolm. I’ve never related to anyone in film or television more than Darlene Conner. (If we’re including books, Meg Murry from A Wrinkle in Time has a slight edge: We share a name, and she wears glasses so … ) Darlene was around my age when the show was on, and I too was the moody, skeptical middle child. A common utterance in my home: “Is that Margaret talking, or are you Darlene now?” It was meant as an instruction to be more polite, but I secretly thought of it as an indicator that I had succeeded somehow — Darlene-ness was what I aspired to. Watching now, it sort of still is.

I meant to re-watch fifteen or so episodes of Roseanne to jog my memory, but I wound up watching closer to 50. In about a week. I love “The Little Sister,” which digs into Jackie and Roseanne’s relationship and was written by someone named Joss Whedon who went on to nothing. I love “Brain-Dead Poets Society,” in which Darlene has to read a poem she wrote, and it’s the most humane and perfect exploration of tween girlhood I’ve ever seen. I love “Friends and Relatives,” written by another nobody, Two and a Half Men creator Chuck Lorre, where Dan and Roseanne have to borrow money from Jackie. “Like a Virgin” finds Darlene in the throes of her first make-out session. The episodes about Jackie and Roseanne’s abusive father — “Thanksgiving ‘91,” “Kansas City, Here We Come,” “This Old House,” “Wait Till Your Father Gets Home” — are biting and honest and hilarious, without being superficial or phony.

All kinds of funny, open people are lugging around heavy baggage. Roseanne has been described by some as cynical or nasty, and that’s wrong. It’s an incredibly optimistic show, one that says “You actually can learn how to love and be loved.” Roseanne and Dan’s imperfect marriage is enviable (at least through season seven); it’s hard not to be jealous of what they have, and, as they joke sarcastically with their children or do goofy bits with one another, hard not to want them to be your parents, too. I felt a little sad re-watching the series: I would love to be blogging about Darlene Conner, Feminist Hero. Or DJ Conner, Underrated Child Character. Or Dan and Roseanne vs. Coach and Mrs. Coach: Who Has The Best Marriage? I could write about Roseanne forever.

Malcolm is a great show. But Roseanne is funnier. And truer. And sadder. And better.

Winner: Roseanne

Margaret Lyons is a Vulture associate editor.