Michelle Zauner knew something was wrong. It was 2021, and she had just released an acclaimed record with her band Japanese Breakfast followed by an even more acclaimed memoir, Crying in H Mart. But the success of both was wreaking havoc on her body. “I was just keeled over with stomach pain before every show,” she says. “It was all stress and pressure and feeling like, I don’t deserve this. People are going to find out that I am an awful singer.” By the end of 2023, she had moved to South Korea to start work on her second book — and recuperate.

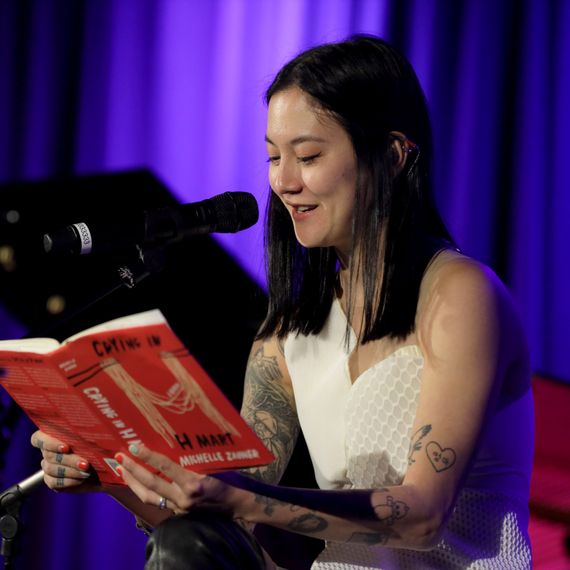

The trip was a long time coming: For nearly a decade, Zauner has been mastering the art of turning personal lore into indie-rock and literary gold. Psychopomp, her first studio album as Japanese Breakfast, emerged in 2016 and chronicled the immediate fallout of her mother’s death; in 2018, Zauner expanded on those memories and her sense of Korean American identity with an essay in The New Yorker titled “Crying in H Mart.” When her full-length memoir arrived in 2021, shortly before the band’s third studio album, Jubilee, the book spent more than a year atop the New York Times’ best-seller list. Taken together, it felt like a genuine celebration: One could finish paging through Zauner’s heart-wrenching story and then witness her bouncing across the stage in a puff of taffeta at Radio City or on SNL with what looked like an inarguably hard-won joy. You couldn’t not root for her.

I recently met Zauner over lunch in New York, where she’s back after spending the past year abroad. It’s clear that her time in Korea not only gave her some professional breathing room, but also a wider perspective on the decisions she’s made. She’s now gearing up for her public return as Japanese Breakfast with the March 21 release of a previously shelved record, For Melancholy Brunettes (& Sad Women). The project touches on her recent artistic success, though its storytelling is both subtler and meatier than what fans accustomed to her popularized first-person register might expect. Instead, she writes vignettes of muddy, moody characters who insist on playing with fire. It’s new lore for a new era, but Zauner remains firmly herself: “All of my ghosts are real,” she sings, almost with a sigh of relief. “All of my ghosts are my home.”

Looking back, it’s wild that Crying in H Mart and Jubilee came out within two months of each other. Was that always the plan?

The record was supposed to come out a year earlier, but the pandemic pushed it. I was like, Two months is enough for them to be considered separate entities. I don’t know what I was thinking. A lot of the press I was doing combined them; they almost felt like simultaneous releases.

I was initially very afraid that something in the book was going to paint my album in a negative light because it was just so open, and I felt that it put the record in a vulnerable position. But they supported one another. The book actually helped the record live a fuller life. I was able to get a lot of opportunities that I wouldn’t have if they were separate, like Late Night or SNL. I’m not sure, if we just had a record out, I would have been considered a large enough artist to be given that kind of opportunity.

Writing a memoir about your mother’s death is as intimate as it gets. Did its success change your relationship with the public? Were fans stopping you on the street and doing drive-by trauma dumps?

I’m at a very cozy level of notoriety where that doesn’t happen very often, and when it does, it’s always a really sweet thing. I almost feel like I’ve been so open with my life and my person that no one wants to know any more. So I feel very left alone.

That’s heartening in light of how so many female artists have been talking about their experience with the parasocial element of fame. Last year, Mitski compared fame to “the shittiest exclusive club in the world … where strangers think you belong to them.” Chappell Roan likened it to “the vibe of an abusive ex.” But it doesn’t sound like that’s been your experience.

What both of those women have said about fame is completely valid to their experience. Honestly, the two of them are much larger artists than I am, and I think they maybe have more obsessive fans than I do. I can totally see why they feel that way. I know Mitski is a very private person, and there are just experiences that she’s had that I haven’t.

Are there boundaries that you’ve set to keep your experience that way?

I do find myself being slightly more cautious in interviews than when I started. I get wild asks from the press sometimes. I’ve had a publication ask for photos of my mother when she was sick, which I found to be really cruel. That’s not for sharing. How dare you even ask for that.

You’ve described For Melancholy Brunettes as a response to the period when you had this breakthrough album and a best-selling novel — everything an artist could ever want. But you also felt a sense of doom. You said, “I was flying too close to the sun, and I realized if I kept going, I was going to die.” Tell me about that.

I come from a DIY background where I’ve been playing music since I was 16 years old, booking shows, promoting myself, touring the country in vans, sleeping on floors, carrying my amp down rickety stairs. So as soon as I was able to begin financially supporting myself by playing music and not having to work at a restaurant on the side, I was like, I’ve won the lottery — I need to just run as fast as I can and do everything and be grateful. I have to keep going at this clip.

When we first went on tour after the pandemic, we were doing six days on for six weeks. And it was crazy. I mean, I said yes to every single interview. I said yes to every single show because I never made money doing that before. And then I started getting crazy stage fright and health problems.

Was there a specific inciting incident?

It might’ve been right when we were playing shows again. You have to remember that this was right after the pandemic. Can you imagine having gone from a year of not seeing anyone to then playing the biggest concerts of your life? I think our first show back was in D.C. in front of 1,800 people. I was freaked out. That whole cycle was very scary for me; I had all of these skin and stomach issues.

And then I went to Korea and it all went away. It was just stress — and not sleeping enough. I was honestly living on anxiety medication for the last three years in order to sleep. I was not eating very much; I lost a lot of weight. I felt like I was sitting at a poker table and I was just winning hand after hand and I was just so afraid of losing the entire time. And all I wanted to do was escape before I lost everything. We were flying a lot; it was really hard on the body, and I remember reading about Jim Croce dying in a plane crash on the way to do a performance. I just got so afraid that I was working towards something that I didn’t really understand anymore.

And then I had friends die. I had a lot of important family events that I was missing. It’s so fun and amazing to travel the world and play shows, but it requires a lot of being absent from your life. It’s an incredibly privileged position, but there were parts of it that were really quite hard. And I think that was sad for me because I had achieved this dream of mine, and parts of it were difficult. I want to be cautious about the way that I talk about it, because it was not lost on me how lucky I was. I think that was part of what made it really challenging.

Did you still feel the financial pressure of touring at the time?

The book afforded me financial security in a way that made me question it: Do I need to go so hard? But it’s tough because there are ten people who are in the band and crew who I feel a responsibility of taking care of.

It seems like touring is only getting more expensive, too.

It’s a huge risk. The money that you put up front before you make anything is really scary. And especially touring during COVID, it was like, This bus costs, like, $1,500 a day. If I get sick, I have people’s salaries and a bus to pay for during the seven-to-ten-day recovery time it takes for me to get back to playing. You just become so obsessed with your health and body, but it’s hard to take care of it when you’re sleeping in a bus and you can’t cook for yourself.

Also, I used to drink a fair amount before playing shows, and I was quickly realizing that that was not sustainable. But how do you throw a party every single day just completely sober when that’s not something that you’ve done before? It was hard for me to learn how to do that. I realized I could no longer even just have casual drinks every night to help me get loose. I was like, I can’t do this anymore. I need to just be an angel and be very well behaved.

Did it feel like you had to “fake it” onstage?

I mean, you just feel awkward. It is a type of acting; you’re acting out a confident version of yourself.

When did you start thinking about taking a year off and going to Korea?

My publisher said, “We will support your next book. We can’t wait for your next one.” And the only idea I had for it was what my mom used to say to me: “If you lived in Korea for a year, I think you would become fluent in the language.” And I was kind of curious to put that to the test. I loved the idea of a project that forced me to focus on one thing and to live a quieter, humbler life in one place.

But I was nervous. The first track on the album was about the fear that I had of telling the band, because I felt incredibly worried about taking their jobs away for a year. They were all supportive, but I felt very, very guilty before telling them that that was what I wanted to do.

How did it feel to be in the motherland? Within the Asian diaspora, that kind of homecoming is a famously fraught experience.

Yeah, I may be guilty of seeing it through rose-colored glasses because the things that are problematic about Korean culture, I felt a bit protected from. It was the first time that I returned to Korea feeling like a successful woman. I could just enjoy the parts that I wanted to, and I didn’t have to work in a company. I didn’t have to date anyone.

Even the etiquette and the rules of certain mannerisms would’ve been uncomfortable for me when I was younger, but it was kind of a fun challenge for me to understand. I enjoyed my time there even though I think I also used to feel so upset that I was never embraced as a Korean person. When people say, “But you’re not Korean,” I’m not so bristly about it because I understand what that really means.

I have this joke with friends where it’s like you go back and think it’s going to feel like, Now this is where I belong! But the mindfuck is that turns out you don’t really belong there, either.

Not all Korean people are like this, but I’ve had some Korean people say to me, “I don’t understand why Korean Americans are so obsessed with our culture.” I feel like it’s so judgmental and unfair because any time a Korean person is trying to stake out a position or find themselves, at least in the U.S., I’m always rooting for them. I think a lot of Korean American people or Asian American people are rooting for them. And it’s heartbreaking to me that they can’t do that for us over there sometimes.

How plugged in to the rest of the world were you while you were on “sabbatical”?

I only consumed Korean content while I was abroad. I didn’t listen to any English music with English lyrics; I didn’t watch any TV or movies. I just wanted to be completely immersed in Korean content. Even in the very beginning, I tried to only text my Korean friends in Korean. I learned a lot about Korean cinema and watched K-dramas. I was interested in learning about older Korean music; that was really fun for me.

Now that you’re home, what do you look at online?

I’m just obsessed with how this record is being perceived. It’s a very self-absorbed thing, but I would love to get offline.

Do you search for yourself?

All the time. It’s terrible.

What is the scariest place to search for yourself?

YouTube comments are pretty brutal. After SNL and every live performance, I try to not read those.

Has your approach to promoting yourself on social media changed this time around?

I feel like I am less unhinged on the internet than when I was younger. I think I was kind of unsure of how I was going to navigate that element of social media and thought that I might try harder, but I just can’t. I’m not going to.

You recorded For Melancholy Brunettes before you left for Korea. Now that you’ve returned and are gearing up to tour for it, does the album itself feel differently to you?

I’m not sure how people will receive it. It’s less of an obvious record and a slower burn. I hope that people take their time with it. But that’s exactly the record that I want to make. And I’m just so excited to get to play guitar again. I think these are some of the best lyrics that I’ve written.

You have Jeff Bridges featuring on “Men in Bars,” which takes the album in an interesting country direction. What’s the story behind the feature?

I wrote this song a long time ago; it was originally a Bumper song, which was a pandemic side project I did with Ryan Galloway. I was inspired by this Kenny Rogers song called “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town,” which is about a war veteran who is pleading with his lover. I loved the idea of having a duet between a man and a woman, kind of like “Islands in the Stream.”

My producer, Blake Mills, and I knew for a long time that this was going to be a good opportunity for a cameo feature, and we passed back different ideas for who could play this role, who had sort of a lower-register voice. Blake had played on a record of Jeff Bridges’s and played me a song of his called “Nothing Yet,” which I thought was so beautiful. So Blake texted him, and Jeff video-called us out of the blue 30 minutes later. He was just super-down. Unfortunately, I had to move to Korea before they could cut his vocals, so Blake and our engineer, Joseph Lorge, went to Jeff’s house to record his part. That’s how that happened. But I’ve never met him.

Will you link up on tour at all, do you think?

I hope so. I’d love to meet him. I designed and ordered my own stationery specifically to write him a letter to say thank you. After I did Conan O’Brien’s podcast, Conan sent me a typewritten letter, from the typewriter, with a little drawing on his own stationery. I thought that was the classiest, coolest thing ever, and I decided I wanted to be that type of person. So I asked my manager if I could make my own stationery.

When you publish a memoir, you have all the control as the narrator. How does that experience compare to releasing a personal album, where you can cloak details in music and metaphor?

I don’t feel particularly cryptic in my lyrics, but apparently I am. It’s interesting having that experience with the book; it’s so rooted in actual moments that you just don’t have the real estate for in songs. But I wrote the song “Orlando in Love,” and I made a video that was very clear to me what was happening. That song is about a whimsical, romantic, foolish man who lives by the sea in a Winnebago and is seduced by a siren. And then when I was doing an interview, the journalist asked me if it was about the pressures of being an ideal woman, because that’s one of the lyrics, and it blew my mind that someone could have that interpretation when it seemed to me so clearly just a fictional story about this man. Sometimes it’s frustrating that that is out of my control.

So it was interesting to me that writing Crying in H Mart was the first time that people really understood. There are certain songs that I think are easier to understand than others, but one thing that I really love about writing music is the freedom to dip in and out of fiction and nonfiction, how you can jump from song to song to a different topic and then you find this narrative thread between them. And yeah, I think that this narrative thread is going to be a little bit more challenging than the one before for some people. I worry about them, but I hope that the ones who get it get it.

How does that compare with, say, writing the Crying in H Mart screenplay for the movie adaptation? What did it feel like to wrestle with the idea that you were ceding control to a new narrator or other storytellers?

Horrible. It was kind of a worst-case scenario for a first feature about the most personal story that’s already lived a life of its own as a successful book. Now you have a bunch of strangers telling you what to change about real people.

The only thing that made me comfortable with that was that I was trying to be honest and fair to them. I would love to have the opportunity to do it again with something that’s a little bit less touchy for me, obviously, because I think that so much of making a film is you have to listen to a lot of people, and that can be a really positive collaborative experience. But I was honestly very defensive and guarded because it’s an extremely difficult, personal story. I come from two mediums where I’ve been given so much freedom. With music, I’ve always been on an indie label, and they’ve never told me what to do in terms of the creative work; I’ve never been given notes.

What kind of notes were you getting on the adapted screenplay?

Mostly just where certain events should go. I was like, But that’s not how that happened! I worried about changing the order of certain events and how it might shed a negative light on certain characters. I will just say that I have amazing producers and people who were involved with that movie, but I think for me, it was a difficult process.

In a recent interview, you mentioned that the Crying in H Mart movie is now on hold indefinitely after director Will Sharpe stepped away from the project. What happened?

We were waiting to get green-lit and then during the writers strike, the director felt that this movie wasn’t going to get made. I think he probably had a lot of other offers; he’s also an actor. I shouldn’t speak too much about it, but he decided to leave, and I think once the writers strike was over, after going through that process already, I was like, I can’t go through that again. I just needed some space away. I mean, I was devastated when Will left. I had a very big meltdown in Hamburg, Germany, when he called and let me know, because it was a year of my life that felt completely down the drain. But I think, if anything, perspective makes the best work. So if I’ve been away from the screenplay for years, when I open it back up again, I think it’s only going to get better from there. I think someday I would like to direct it.

I was going to say: You’ve directed a few of your music videos.

But I don’t feel ready. I’m still working with my producers about a long-term plan to see that to fruition, but I’d rather it not be a movie than a bad movie. So I don’t want to take it on until it’s something that I feel ready to do.

I have amazing producers, and I would love to make a movie with them. But I think I need to learn how. I don’t want to learn how to direct on that feature.

You mentioned in a recent Korean interview that you want to be a mother this year. Talk about complicated desire! Or is that one actually more straightforward than all the others?

No, it’s incredibly complicated. It’s something that I pushed and pushed and pushed down the road. I mean, I’m hesitant to talk about it. I don’t know how difficult it will be for me, but so much of this record is fixated with this kind of anticipatory grief of the artistic life that I may have to leave behind in some capacity. Or it might change in a great way.

I think of these incredible women like Dolly Parton and Stevie Nicks, who never made that sacrifice for their work. I mean, who knows why they decided not to have children. But I think there’s a part of me that feels like, Well, my artistic work is my child. I know a lot of working-women mothers who are doing an incredible job, but it’s an enormous loss of time and physical ability to bring a child into the world. And I’m very worried about how that will impact myself and my work, but it’s also something I am really interested in and excited for.

So looking ahead to the tour: How are you doing it differently this time? We’re not doing six days on anymore, right?

Now it’s four days. I think that when you get to be a bigger artist, it goes from saying yes to everything to the power of no. That was something that Karen O gave me when we played together at Forest Hills: “You need to learn how to say no.” There’s value to no, beyond just your sanity, because it has the potential to lead to bigger opportunities if you feel comfortable walking away.

I would like to have fun again. It used to be so fun for me.

And it isn’t at all anymore?

I mean, even when it is difficult, there are times when the adrenaline kicks in and it’s fun. It’s just all of the moments leading up to it. It’s just physically demanding and difficult, but I think that I’ve learned about some boundaries that will make it easier for me to be able to meet those demands. I don’t think I knew what those were beforehand, because when I was younger, I was just able to do it. I also went through some growing pains on this last record around becoming a bigger band: not being able to just be a young person drinking and sounding like shit and instead realizing that there’s a certain responsibility that comes with playing larger rooms and charging higher ticket prices. You have to approach it with a certain professionalism. Because, suddenly, I had people in my band who were classically trained, and I felt very inferior and self-conscious around them.

I feel like people always talk about impostor syndrome being this really awful challenge that we have to rid ourselves of. Karen Chee actually has a joke about this — about how most people are not really good at things naturally. You want to be a rock star? Chances are you are a fucking impostor! What do you have to do to prove that you deserve to be there? You put in the work. I feel more comfortable now that I have more time to put in the work than when I had to figure it out on the road at that time.

I actually saw a fortune teller before I left Korea, and I was like, “I had really bad stage fright the last few years. Is that going to be a thing?” And she was like, “You’re a Year of the Snake. It’s your year. You’re not going to feel that way anymore.” I’m just choosing to believe her wholeheartedly and see that to fruition.